Four events highlight the history of the Toledo, Peoria and Western Railway: two spectacular accidents, a visiting steam locomotive, and a murder. Remarkable is that the TP&W rebounded from the negative incidents to last through 1983, when it was merged into the Santa Fe Railway. After three years, though, Santa Fe wanted out, and the regional came back, using its old name, and today survives under its third post-Santa Fe owner.

TP&W’s early years were marred by a disaster when, in the darkness of Aug. 10, 1887, a 15-car excursion train carrying 800 people from Peoria to Niagara Falls plunged through a small, fire-weakened trestle east of Chatsworth. The telescoping wooden cars caught fire as they piled up, and more than 80 passengers died. Today a historical marker along U.S. Route 24 — a half mile across fields south of the wreck site (long ago made a culvert) — commemorates the tragedy.

What would become the Toledo, Peoria and Western originated with a desire to link the Illinois River at Peoria with the Mississippi River, first at Warsaw, Ill., then Oquawka, 45 miles upriver. The Warsaw line saw little track laid, and in 1849 the Peoria & Oquawka was chartered. Three years later, the P&O Eastern Extension (“P&O East”) was chartered to the Indiana border, laying the foundation for the TP&W’s cross-Illinois character.

Oquawka was ambivalent about a railroad, so P&O aimed for East Burlington, Ill., 10 miles downriver, and after what in 1855 would become the Chicago, Burlington & Quincy tied into the P&O at Galesburg, P&O in 1862 became a CB&Q property. Meantime, P&O East opened to El Paso (an IC connection) in 1856 and to Chenoa (on an Alton predecessor) in 1857, the year it finished building an Illinois River bridge at Peoria. In 1859 it reached State Line, Ind. (later Effner), meeting the Logansport, Peoria & Burlington, and P&O East was renamed to LP&B in 1861. In an 1864 foreclosure, one of several, LP&B took the new name Toledo, Peoria & Warsaw, and constructed a yard and shop in Peoria south of where Union Station would be. The enterprise would never get close to Toledo, Ohio.

The road reached Warsaw in 1868, in conjunction with the Mississippi & Wabash (which wound up in the Wabash family), and they jointly owned the Keokuk & Hamilton Bridge Co. The name Toledo, Peoria & Western first appeared in a December 1879 reorganization. The Peoria bridge was replaced in 1890 and Keokuk’s in 1915 (a double-deck rail-highway span that still carries railroad traffic).

Besides expansion, an objective became to haul east-west traffic bypassing busier Chicago and St. Louis. Overhead traffic has fluctuated in importance, but Peoria grew and began to originate manufactured goods by rail. Including adjacent East Peoria and neighboring Pekin, Peoria became a rail gateway on its own, served in 1960 by a dozen Class I railroads.

TP&W’s bridge-traffic era took a long time to blossom, because in 1893 the Pennsylvania Co. purchased a controlling interest, soon joined by CB&Q as joint owners. This meant TP&W handled only local traffic because its owners also served Peoria. TP&W began to starve.

Colorful Toledo, Peoria And Western Leaders

Three Toledo, Peoria and Western presidents rate mention. George P. McNear took over in April 1927 as sole bidder after a 1926 foreclosure when PRR/CB&Q gave up. McNear overhauled the property and restored profitability. He discontinued a CB&Q connection at Burlington, Iowa (the old Oquawka route), and built one at Lomax with Santa Fe. In July 1928 he opened a new yard in East Peoria, sold the Peoria facility to terminal road Peoria & Pekin Union, with which TP&W was not on good terms, P&PU being owned by other Class I railroads. McNear also got off P&PU tracks west of Peoria by securing rights on CB&Q and Rock Island’s Peoria Terminal to Hollis (near Sommer).

McNear was good at business but not with people, and his hard anti-labor stance would set back TP&W severely. After an 84-day strike beginning in late 1941, the federal government, with the nation at war, seized the TP&W in 1942, naming John W. Barriger III as manager. Federal control ended in October 1943, and the 13 unions resumed their strike, which lasted 580 days. After two strikers were killed in a gun battle at Gridley in February 1946, McNear closed the railroad. A year later, on March 10, 1947, he was gunned down hear his home in Peoria; his murder was never solved.

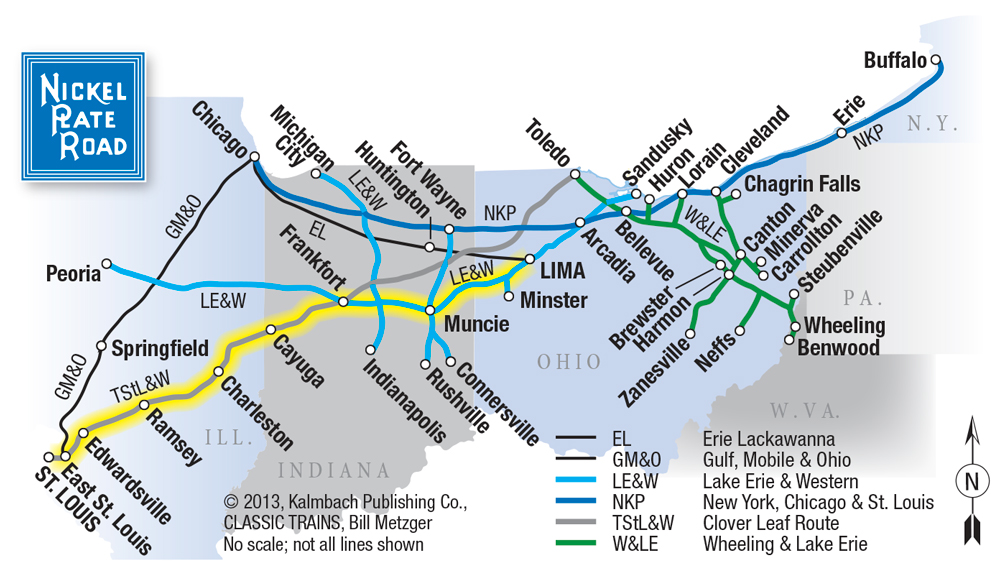

TP&W’s next leader was J. Russell Coulter, off the Frisco; he became TP&W president on May 1, 1947. The railroad prospered after the war, as both a bridge line and Peoria traffic originator. Only one other Class I railroad went through Peoria—C&NW, which had a north-south line—so TP&W enjoyed hefty interchange traffic with Minneapolis & St. Louis, Burlington, Nickel Plate, Pennsy, and NYC’s Peoria & Eastern. Half of Peoria’s roads, including TP&W, CB&Q, Rock Island, C&NW, and interurban Illinois Terminal, had their own yards, while six used P&PU’s large East Peoria yard. In its imaginative postwar era, TP&W used slogans playing to its initials — “Transcontinental Peoria Way” and “The Progressive Way”—although another, “Links East and West,” was more to the point. Color schemes and decorations on its freight cars were almost as numerous as its freight-car types.

Passenger service never amounted to anything after state highways paralleling the TP&W were paved in the 1920s, having been cut to mixed-train service before the 1926 foreclosure. The trains handled mail until 1929; eventually any passengers rode in the caboose, a service that lasted into the 1970s!

Under Coulter, TP&W’s track east from East Peoria yard was relocated as part of a flood-control plan for Farm Creek; TP&W gained an easier grade out of the Illinois River valley and a bridge over the Nickel Plate at Farmdale, replacing an interlocking. West of Peoria, TP&W and C&NW bought lineside land and created an industrial park at Kolbe.

Meantime, Santa Fe and PRR began eyeing the property as a natural link, and became joint owners in 1955. TP&W traffic reached all-time highs in the 1950s and ’60s, but the modern merger movement put the writing on the wall for it as a bridge line, beginning with C&NW’s absorption of M&StL in 1960. Next was N&W’s 1964 takeover of NKP and Wabash, which reached Kansas City. Meantime, Santa Fe set up an alternate Chicago bypass route via NYC at Streator, Ill., although TP&W negotiated rights on Santa Fe from Lomax into Fort Madison (Shopton), Iowa, for better interchange. The Penn Central merger was a big blow — P&E reached NYC’s new Avon Yard near Indianapolis, lessening the importance of TP&W’s outlet at Effner. When PC went into the new Conrail in 1976, TP&W was forced to buy the 63-mile Effner-Logansport line to keep any bridge traffic left; the last 6 miles, from Kenneth, were on Conrail rights.

Typical Steam, Eclectic Diesels

Toledo, Peoria and Western’s early 20th-century steam power was typical: Ten-Wheelers and Consolidations, joined by two Pennsy 2-8-0s and four from Big Four, plus four 2-6-2s from CB&Q in the 1920s, augmented by four new Richmond 2-8-2s in 1927 and then TP&W’s ultimate, six light Alco 4-8-4s in 1937. The lithe Northerns lasted only 13 years.

I first became acquainted with TP&W in 1961 when I was about to enter college 70 miles south of Peoria, and friend Dick Wallin introduced me to the late M. L. “Monty” Powell, a TP&W operator. Like our mutual friend Paul Stringham of Peoria, Monty was a true Illinois rail historian, and he would become a TP&W train dispatcher.

As a diesel fan, I was drawn by TP&W’s eclectic roster. Its three Lima-Hamilton switchers had been sold in 1958, but it still had 14 units (4 EMD, 11 Alco) encompassing 5 models. TP&W would trade in its two F3s on a GP18 and a GP30, and then, three of its seven RS2s for GP35s (which rode on the Alcos’ trucks). The F3s had been an A-B EMD demonstrator duo, but TP&W fabricated a cab and made the F3B into an F3A! (TP&W’s shop forces also built all its own steel, bay-window cabooses, six in 1940 and six in the ’50s.)

Alco gave TP&W a deal on two new C424s in 1964, and TP&W got an EMD loaner GP40 in 1969 before finishing its diesel purchases with 11 GP38-2s in 1977-78. Four new SW1500s, two each in 1968 and ’70, replaced RS2’s around Peoria and also introduced a new red-and-white livery, replacing olive green and gold. TP&W entered 1983, its last autonomous year, with 31 units: 8 Alcos (3 RS11s, 2 RS2s, its lone RS3, and the 2 C424s), and 23 EMDs of seven models, including both GP7s. All wore some variation of red and white. The Alcos, SW1500s, GP7s, and GP18 were sold before the takeover by Santa Fe, which kept the GP30, GP40, and GP38-2s.

Tough times on Toledo, Peoria and Western

The year 1970 was not kind to Toledo, Peoria and Western. On Feb. 12, a barge tow took out its Illinois River bridge in Peoria, forcing an ultimately permanent detour via P&PU’s bridge downstream when TP&W could not afford a replacement. Then on June 21, a burned-out wheel bearing on a CB&Q covered hopper in 108-car train No. 20 caused it to derail in Crescent City, seven miles east of Gilman. Cars behind it piled up, including nine tanks loaded with liquefied petroleum gas, which erupted in a series of explosions. The resulting fireball destroyed 15 freight cars, 16 businesses, and 25 homes, and damaged numerous other freight cars, seven other businesses, and many more homes. As a result, 66 people were injured, but miraculously there were no fatalities; the fire burned for 56 hours. On the same day, Penn Central declared bankruptcy. Crescent City remembers the disaster with a display pavilion containing bulletin boards with news clippings in a city park.

TP&W in 1980 enjoyed its most shining modern moments. Traffic was holding up, but it was the eve of the deregulation that would help doom the classic “Tip-Up,” as many called it. In May 1980, Robert E. McMillan, TP&W’s last pre-Santa Fe president, imported a little fun. Also a rail historian and enthusiast, he approved the brief appearance of Fort Wayne, Ind.-based Nickel Plate 2-8-4 765. For a few weeks, the Berkshire worked out of East Peoria, hauling freight, acting as helper east up Farmdale Hill, and pulling passenger excursions.

Three months later, on Aug. 10, began the brief reappearance of passenger service, the state-supported Amtrak Prairie Marksman to and from Chicago via Chenoa and ICG’s St. Louis main line. The little train left in the morning from a small metal depot in East Peoria yard and returned in the evening. Rock Island had ended its Peoria-Chicago passenger train at the beginning of 1979, but to many residents, East Peoria wasn’t Peoria, and the service lasted only until Oct. 4, 1981.

At the end of 1983, TP&W became part of Santa Fe’s Illinois Division. Santa Fe tried to infuse traffic by building Hoosier Lift, an intermodal ramp at I-65 in Remington, Ind., but it couldn’t compete with Santa Fe’s own Chicago facility. In December 1986, ATSF sold the 33-mile La Harpe-Warsaw/Keokuk portion to short line Keokuk Junction, which dated from its 1981 takeover of RI’s Keokuk trackage. In February 1989, Santa Fe sold the Lomax-Logansport line to a group led by Gordon Fuller, which reincarnated the old name: Toledo, Peoria & Western Railway Corp.

Soon, the new TP&W and BN signed a 10-year pact marketing intermodal traffic out of Hoosier Lift, but it never took hold, and the BNSF merger in 1995 made it redundant. As a BNSF merger condition, and for a better interchange than Fort Madison, TP&W gained rights on the former BN from Peoria to Galesburg — the same line its ancestor Peoria & Oquawka had built! In many ways, then, TP&W had come full circle.

The new TP&W’s post-Santa Fe history has added chapters. In 1996, Fuller’s group sold TP&W to Delaware Otsego, parent of the Susquehanna, and in 1999, DO, with the Susquehanna suffering under the Conrail split, sold TP&W to RailAmerica, which continues to run it, from East Peoria east to Logansport and west to Galesburg. RailAmerica saw no future for TP&W’s Lomax route, and after a long battle with regulators and a would-be buyer that might have scrapped it, Keokuk Junction parent (since 1996) Pioneer Railcorp in 2005 was awarded the TP&W’s 76-mile “west end” (Kolbe-La Harpe-Lomax). So, like the legendary Phoenix, the “classic” TP&W survives, and under two banners.

This article is dated Sep 1,2022, but ends with RailAmerica in 2005. Since then, Genesee & Wyoming has taken over, and attestable to the importance of the TP&W, retains its original, three word name. Most of the action now is in eastern Illinois and Western Indiana. TP&W trains actually make it to Kokomo, IN ! I have seen at least one photo posted of a TP&W unit leading 2 NS units to Kokomo !

The elevator in Cruger, IL and a new one in Meadows/Chenoa, IL handle unit grain trains now, and the BNSF runs grain trains to Peoria quite frequently. These become TP&W trains with TP&W crews and are quite the sight running to Cruger and Meadows/Chenoa with mainline BNSF power,

TP&W even has a unique locomotive. A single, spotless GP15 in TP&W (G&W) orange with a new mainline type horn ! It leads as often as not. I will recommend that our present president of the TP&WHSII contact you.

David P. Clark

Washington, IL

I was traffic manager for Foote Mineral which had a facility in Keokuk. In conjunction with the plant shipper, many cars of silvery pig iron were routed east via TPW as well as inbound scrap from Peoria. My contact was George Pacocha, a Santa Fe employee assigned to TPW. He and Bob McMillan arranged a cab ride for me one evening from the E Peoria yard over the Mississippi. That was with a full crew (three in the cab, two in the caboose) which could not have helped their competitiveness at that time.

Larry Blazynski