When we think about railroads, we often think first about the rolling stock or the physical plant—the locomotives and cars; the tracks, bridges, signals, and stations. The world of railroading is filled with fascinating equipment and structures, but ultimately, it takes people to make the trains run. The people of railroading also offer one of the best opportunities to share the stories of railroading with wide audiences.

Railroaders: Jack Delano’s Homefront Photography, a new exhibition prepared jointly by the Center for Railroad Photography & Art and the Chicago History Museum, does just that. The exhibition opens April 5 at the museum (www.chicagohistory.org, 1601 N. Clark Street) and will be on display for sixteen months, until Aug. 10, 2015. It presents the portraits and biographies of 49 Chicagoland railroad workers from World War II, along with several contextual photographs as well as railroad-themed environments, activities, and multimedia installations.

We often think of World War II as being the last great stand for the American steam locomotive, which it was, but it was also the last great stand for the steam-era American railroad workforce. Sweeping technological changes in the years and decades following the war, led by the conversion from steam to diesel power, dramatically improved the efficiency of the nation’s railroads while enabling drastic personnel reductions. In 2014, people still make the trains run, but it takes far fewer of them than it did 70 years earlier.

Railroading in the 1940s took people with a lot of stamina and brute strength, but also great knowledge of their craft and sound judgment. Railroading still requires all of that today. Some aspects of railroad work haven’t changed, like being constantly on call, working in all kinds of weather, and frequently sleeping away from home. Other aspects have changed greatly.

Put yourself in the shoes of a 1940s train crew. There are no handheld radios, and you have no direct contact with the dispatcher, the person who decides what your train and every other train on the railroad is supposed to do. You have to rely on the timetable, your railroad watch, your train orders, your senses, and the other members of your crew. Every unscheduled stop requires the rear brakeman to run down the tracks behind your train and provide flag protection against any following trains. Every switching move requires a cryptic combination of whistle and hand or lantern signals.

The railroad industry, like the rest of the nation, had just emerged from the Great Depression. For most railroads, that had meant ten years of deferred maintenance and reduced capital spending. Then with the war, traffic levels quadrupled, almost overnight. Railroads hauled seventy percent of the nation’s freight during World War II and ninety percent of the military freight traffic. Wartime railroaders had to do this with equipment that was often twenty to thirty years old, or older.

Train service employees are the most visible railroaders, but in terms of the railroad workforce, train crews are just the tip of the iceberg. Working in the shops and yards almost completely out of public site were armies of railroaders in supporting roles. Unlike many train crewmembers, yard and shop workers typically get to sleep at home, but during the war, they frequently worked twelve- to sixteen-hour days without a day off for weeks on end. They held together the aging equipment that helped power American railroads through the war.

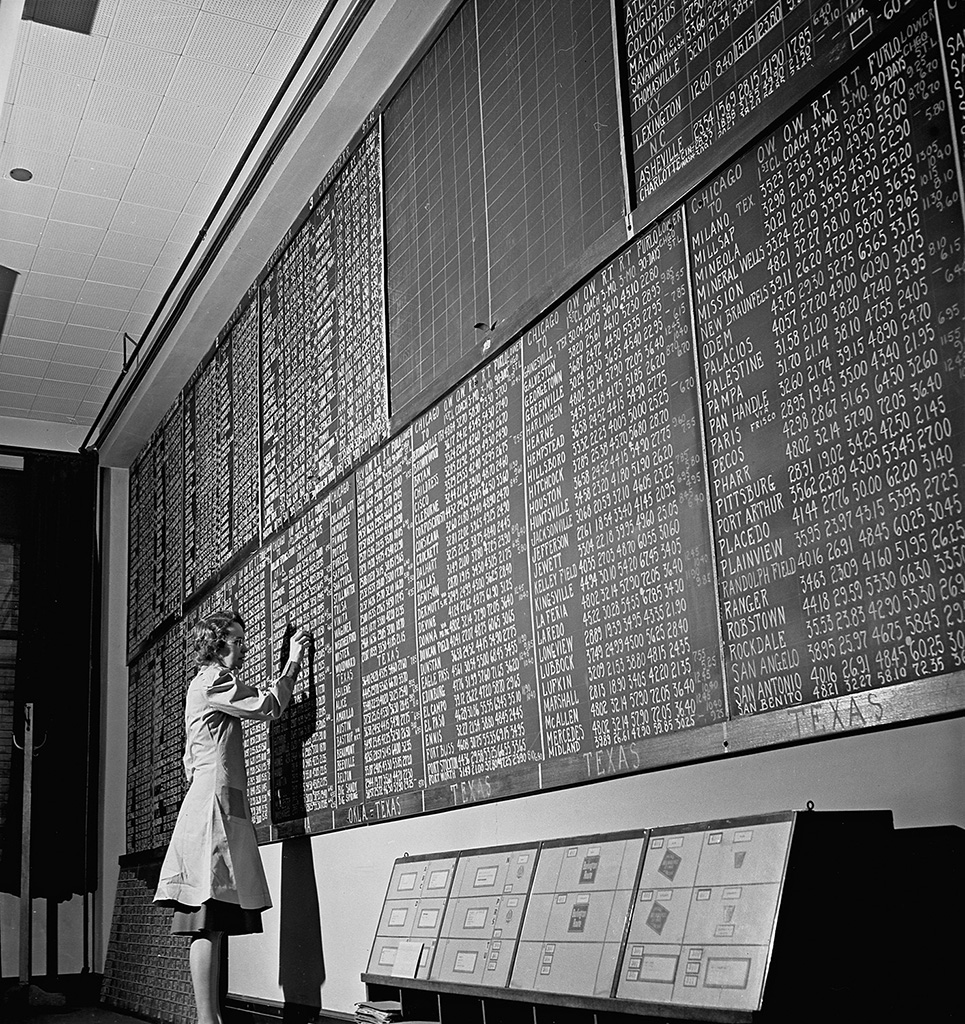

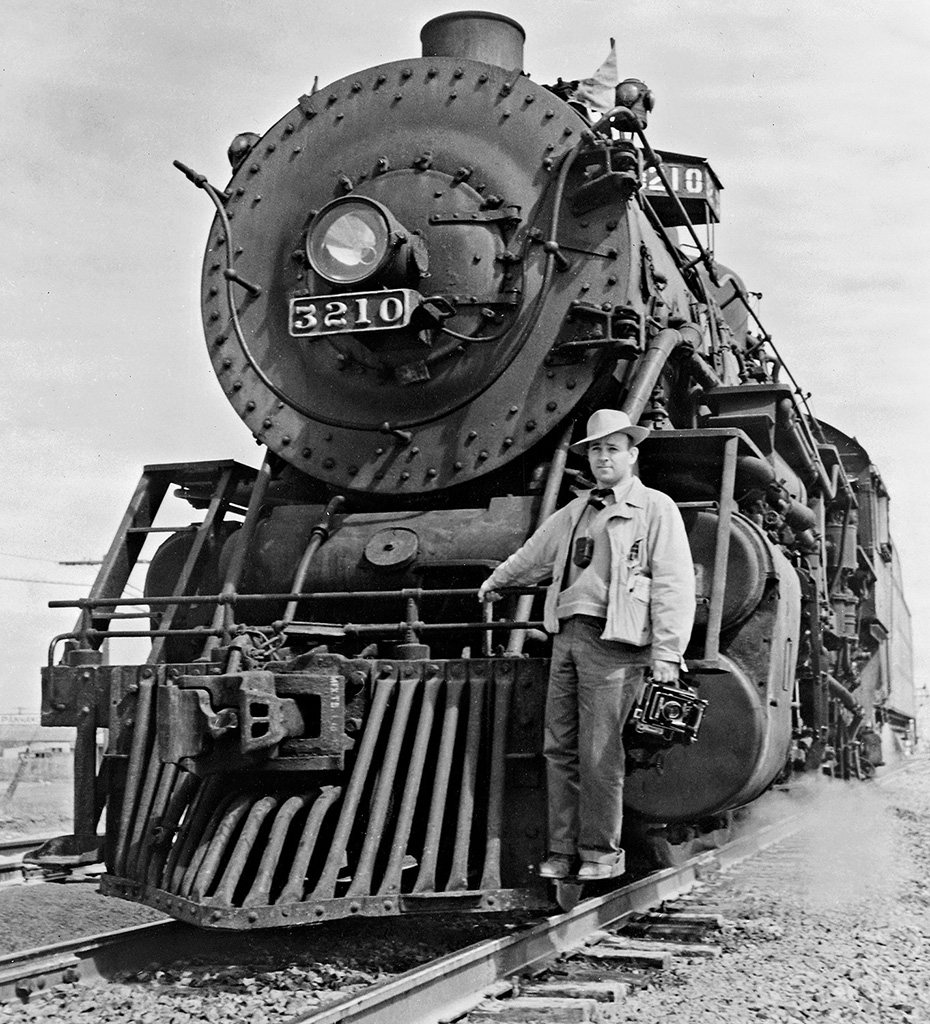

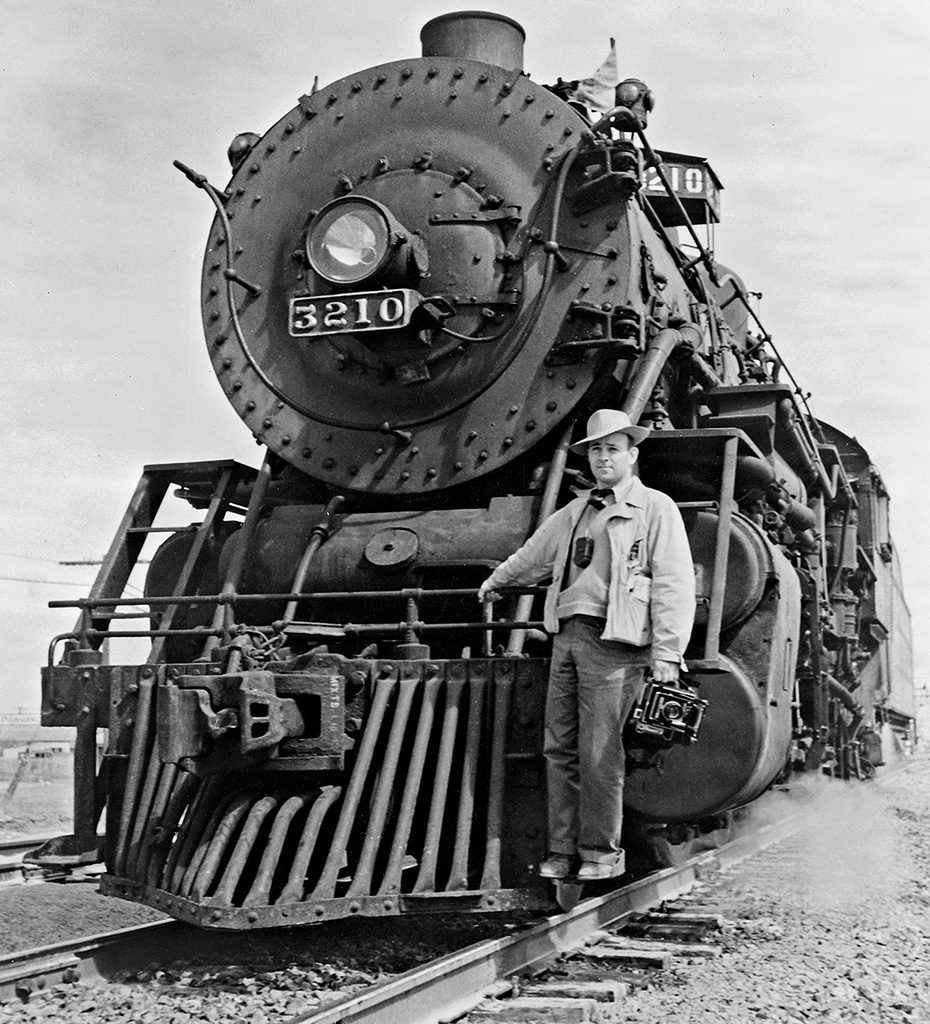

Jack Delano photographed railroad workers of all kinds during his six-month assignment to document the railroad industry as part of the American homefront effort in 1942-1943. He worked for the federal government’s Office of War Information (OWI), successor to the Depression-era Farm Securities Administration (FSA) whose famed photographers included Walker Evans and Dorothea Lang. Delano’s images of railroads and railroad workers are every bit as powerful as the best of the FSA images. Delano spent most of his time in Chicago, the nation’s railroad hub, where he was given access to photograph almost everywhere he wanted to go. He produced some three thousand photographs for the project, with nearly two thousand of them made in and around Chicago.

Like all FSA-OWI photographs, Delano’s images are today in the public domain and available through the Library of Congress. Starting there, the staff of the Center for Railroad Photography & Art did extensive genealogical research to track down descendants of Delano’s portrait subjects, conduct interviews, and construct biographies of the people in the pictures. The stories range from uplifting to heartbreaking, spanning the full sweep of the human experience. Center founder John Gruber and Pablo Delano, son of Jack Delano and himself a talented photograph and professor of fine art at Trinity College in Hartford, Conn., visited many of the descendants to make contemporary portraits, tying the past to the present.

Through these stories of everyday railroaders’ lives, and through the superb curatorial, design, and installation work of the Chicago History Museum, we are presenting the great importance of the railroad industry to the United States and the tremendous importance of everyday workers to the railroad industry. By looking at the lives of the workers, we can engage much wider audiences on both of these points. People love stories about other people.

Scott Lothes is a frequent Trains contributor and serves as president and executive director of the Center for Railroad Photography & Art in Madison, Wis.

The Center has published a 200-page, hardbound catalog to accompany the Railroaders exhibition, and it is available for purchase online:

http://www.railphoto-art.org/railroaders-catalog/

FULL SCREEN

FULL SCREEN

The picture showing the yard office for Yard 9, the receiving yard at Proviso, was my grandfather’s office as yardmaster of Yard 9 until his death in 1936. Found this picture a couple of years ago and it shocked me realizing this was the office of a grandfather I never knew!