First of two parts

EFFINGHAM, Ill, —What happens when electrical current connected with signal systems doesn’t reliably travel from one rail to another when a train passes? Dispatchers “lose” the train — it disappears from their screens — and warning lights don’t flash or gates don’t lower at highway crossings as the train approaches.

The phenomenon is called “loss of shunt.” As rail safety issues go, this is one of the most serious anomalies railroads face. What is perplexing is that it may occasionally occur anywhere.

If it happens repeatedly on the same route — usually where fast passenger trains are involved — a host railroad can impose requirements to mitigate the consequences should a loss of shunt event take place. These may include setting an “axle count,” a minimum number of passenger cars plus the locomotive for each train; mandating the type of equipment used and its corresponding weight; reducing maximum allowable speeds; or any combination of these, based on evidence showing what has successfully prevented the issue from surfacing.

In mid-August, the latest installment of an ongoing series of tests was staged out of Canadian National’s Effingham yard in southern Illinois. The sessions, attempting to seek a permanent solution for locations where loss-of-shunt issues are ongoing, were attended by participants from CN; Amtrak; the Federal Railroad Administration; the Illinois and California transportation departments, and equipment vendors. More testing is set for September.

Loss of shunt was initially detected on some lines in the early 1950s when railroads first deployed relatively lightweight Budd Rail Diesel Cars. More recent concerns and remediation protocols date from the reinstatement in 2009 by Canadian National of a 60-mph “temporary” speed restriction for all trains with 30 axles or less. It had been imposed on CN’s ex-Grand Trunk Western Flint Subdivision in 2004 after a highway warning device failed to activate.

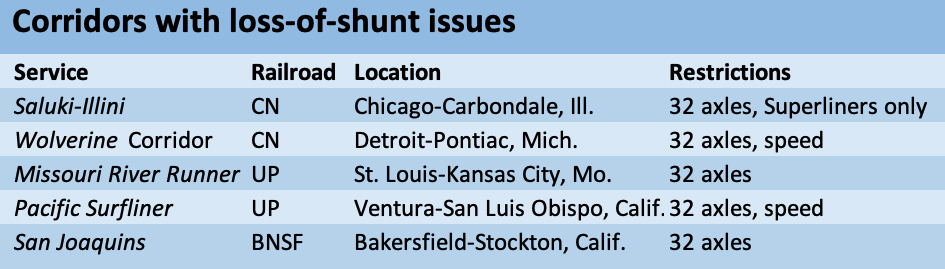

Since then, a number of Amtrak routes have been impacted by railroad-imposed requirements. Trains News Wire sources have provided the information in the table below, although a comprehensive list of routes and exact restrictions awaits confirmation:

For more than a decade, Canadian National has required a minimum number of axles on the Chicago-Carbondale route, which also hosts the City of New Orleans. The City has operated with Superliner sleepers, diners, Sightseer lounges, and coaches since 1994, but up until sometime in 2020, Amtrak was able to utilize single-level Amfleet and Horizon coaches on the two Illinois-supported trains.

To meet CN’s axle-count requirements, heritage baggage cars and unoccupied dining cars were added. After that equipment was decommissioned, Viewliner II baggage cars filled out the consists. This is still the case in Missouri, where Missouri River Runner round trips from Kansas City, Mo., to St. Louis and Chicago over Union Pacific’s Sedalia and Jefferson City Subdivisions operate with baggage cars or unoccupied coaches and cafes. Yet there are no similar requirements on UP’s recently upgraded 110-mph route in Illinois. On California’s San Joaquins, an unoccupied Comet coach is often added between bilevel California Cars and the locomotive.

This non-revenue producing equipment adds to the cost of providing service for Amtrak and each state. However, CN’s edict requiring seven Superliners on the Chicago-Carbondale route is the most consequential. The railroad contends that only the heavier cars (151,000 to 174,000 pounds each) ensure proper shunt.

Given the fact that safety is always paramount, CN has invested heavily in shunt monitoring equipment. The railroad says empirical findings have consistently shown that the wheels of a Charger or P42 locomotive plus seven single-level Amfleet, Horizon, or Venture coaches (weighing 106,000 to 119,000 pounds) do not reliably provide a path for signal current to flow between the rails.

As a result, capacity on Amtrak’s intercity network has been adversely affected while a rotating collection of 14 sleeping, dining, lounge, and coach cars have been tied up on the two Illinois daytime round trips. Virtually every Superliner-equipped long-distance train, except the City of New Orleans, experiences near-daily sellouts.

Why one route encounters erratic shunt issues and others don’t remains unexplained.

Canadian National doesn’t have a Superliners-only requirement on its Joliet Subdivision out of Chicago or the Holly Subdivision used by Michigan’s Wolverines between downtown Detroit and Pontiac, Mich.

But the railroad has been actively leading a National Shunt Committee task force to find solutions. About every two weeks, CN hosts an online meeting involving participants from the FRA, Amtrak, state transportation departments, signal system vendors, hardware manufacturers, and host railroads to discuss testing ideas, data, and results where loss of shunt occurs.

That’s what the August tests along the Illini-Saluki corridor at Effingham were all about.

Wednesday: Part 2 of this report discusses findings to date.

I would guess routes without frequent service build up oxide on the rails and light cars don’t bear down enough to make electrical contact. I remember the RDC problems, and I believe part of the issue was the “Rolokron” anti-skid device which never let the wheels slide, so they were never burnished during quick stops. I believe something like wire brushes were attached to the frames to keep the wheels nice and shiny.

Of course, CN could also solve the problem by increasing the voltage at the track. But that would be too simple a fix, I guess.

Ever since restoring daily service two years ago. Superliner supply has gotten worse instead of better. While availability of these cars has been further depleted thanks to a couple of derailments and management’s failure to prioritize returning the countless amount of equipment that is parked in the yards, they seem to think of anything but suspending these two trains that are holding back a bunch of scarcely available Superliners!! This summer one Illini trainset operated with as many as 3 transition sleepers in its consist. Meanwhile, these cars have yet to return to service on the Capitol Limited, Southwest Chief, Sunset Limited, and the Texas Eagle! Most of those trains are running with just a single sleeping car that also serves a crew dorm. Seriously?!?! Suspend these trains until a resolution can be resolved with the shunting issue! Better yet, why couldn’t Amtrak lease some boxcars to make for the axle count. Surely those cars would be heavy enough. It’s so ironic that Amtrak is doing all they can to cut costs instead of attempting to grow ridership and revenue on routes like the Capitol and the Eagle that have no traditional dining service, no sightseer lounge, and just a single sleeping car. Yet they are incurring extensive operating costs on the Chi-Carbondale trains by running a bunch of empty Superliners to meet an axle count instead of deploying those cars for revenue service. Only 4 of the cars at most are used for revenue service. At other times it might be just three.

Single Budd RDC’s had a problem with shunting track circuits from the beginning. An RDC-1 weighs 118, 300 lbs. Budd developed an “excitation device” that would shunt signals. Without the excitation device, a single RDC had to be protected by a manually block behind it, and the engineer had to approach all signalled grade crossings prepared to stop.

Why no such device can shunt these lines is an interesting question. Is it a different signal vendor?

I recall a recent report of ‘loss of shunt’ on an eastbound Empire Corridor train that resulted in its termination in Syracuse, NY. I hadn’t heard of this problem in this territory before, but perhaps it’s more common than I’m aware.

https://www.fcc.gov/media/radio/m3-ground-conductivity-map

The link is ground conductivity map.

Boxcars, concrete added for ballast, cables for HEP—should be cheaper than putting non revenue miles on much needed passenger cars.

Surprised that shunt is still analog in nature. Should be digital (you would think).

Instead of loading it up with just a voltage, modulate the voltage and pass shunt quality data through it.

One interesting detail of the former RDC shunting problems mentioned: Rail lines that experienced shunt problems with single RDCs tended to be in coastal climates with salt air, such as on the Boston & Maine, New Haven, and Pennsylvania-Reading Seashore Lines. The latter’s rulebooks even included orders that if an emergency stop was made, to then immediately pull forward–because RDC emergency stops dump sand that can interfere with the shunt between the RDC wheels and the railhead, and show a clear signal to a following train. I haven’t seen whether similar problems were encountered with other single/double RDC users such as Santa Fe, Northwestern Pacific, or Western Pacific.

Items:

1. Is it possible that the Amtrak wheel profile is different enough from freight cars that is contributes to this problem. Have noted that some IM cars passing here have a different sound on track than other (?) IM cars do?

2. Does Amtrak still own some Material handling cars that are HEP capable.? Are they usable up to 80 MPH if loaded? Are the ones equipped for HEP still on property? If so, why not ballast them and run them on rear of the required trains. Amtrak seems to keep hoping problem will be solved soon that has decades of being a problem? Saving costs? Amtrak might even be able to sell some LTL space depending on that not having any effect on schedule. Time for congress bring up on hearing for board members.?

3. Now what is causing this problem? Is it wheel profile? This problem seems to be centered in the Midwest. AM radio engineering has to consult ground conductivity maps to predict how AM radio waves will interact and for how far signal will go. Cannot remember but maybe ground conductivity in the Midwest area is much higher than rest of country?

I can’t help but think this has as much to do with the rail as any equipment on it! LIke maybe it doesn’t get enough use.

Did this issue happen much with track circuit relays or mostly with electronics? Have they ever tried simply raising the track circuit voltage a bit?

I guess we have to wait for Part 2 to read about the shunt enhancers being tested.

Great report Bob, looking forward to part two.

A lot of negativity has been directed at CN over this when it is obvious at real issue.

CN allows VIA to operate a train of two or three LRC coaches, total 12 or 16 axles at 80 MPH without any issue so looking forward to the findings

Here is link to ground conductivity map that I found. Draw own conclusions especially around CHI – south and southwest.

https://www.fcc.gov/media/radio/m3-ground-conductivity-map