Surface Transportation Board Chairman Martin J. Oberman ruffled some feathers this month when he said railroads’ drive for ever-increasing profits resulted in a loss of market share to trucks over the past 15 years and continues to restrain growth today.

Oberman cited STB figures that show a decline in rail traffic between 2006 and 2019 despite broad economic growth. His tally, based on STB waybill data, excludes coal. Between 2006 and 2019, “adjusted carloads” fell 1.3%. To calculate adjusted carloads, the STB estimates the number of flatcars required to handle reported container volumes, then marries this with carload data.

What irks some in the industry? Other data tell a different story.

Excluding coal, Association of American Railroads figures show that ton-miles grew 10% between 2006 and 2019. Ton-miles peaked in 2018, before the Trump administration’s trade wars crimped some traffic, particularly grain exports and international intermodal.

Traffic excluding coal also is up slightly if your yardstick is carloads and intermodal units that terminate in the U.S. AAR data show that since 2006 terminating carloads and intermodal units rose nearly 8% through 2018 and 4% through 2019. Measuring terminating carloads – not just originations – is important because it captures traffic generated on short lines as well as the significant shift of U.S. West Coast international container volume to ports in British Columbia.

To muddy the waters further, AAR data for carloads and intermodal units originating in the U.S. paints yet another picture: Traffic in 2018 was up slightly from 2006 levels, while in 2019 it was a tad below 2006 volume.

You’d think that determining the extent of rail traffic growth or contraction would be a cut-and-dried matter. Instead, it’s a data trap.

That’s beside the point, Oberman said in an interview with Trains. The issue, he says, is that railroads have shown no meaningful growth. During his speech to the North American Rail Shippers conference on Sept. 8, Oberman placed the blame for this solely on the Cult of the Operating Ratio. “The railroads’ emphasis has not been on growth,” Oberman said in his speech. “Rather the emphasis has been on cutting in pursuit of the almighty O.R. down to below 60%.”

Oberman concedes that this is just one of many factors that have contributed to rail’s volume struggles compared to truck. Those other factors include economic changes that have nothing to do with railroads, such as the bust of crude by rail and related frac sand shipments, the decline of homebuilding since the Great Recession, and shifting trends in manufacturing, from steel to auto production. And then there are self-inflicted issues where railroads fall short of truck, including on-time performance, providing shipment visibility, and ease of doing business.

Yet the STB chief looks at all this and concludes that railroads need to do more to grow.

Rail and Truck Share Changes

Jason Miller, associate professor of logistics at Michigan State University’s Eli Broad College of Business, says slower rail traffic growth has more to do with changes in the economy than anything railroads have done.

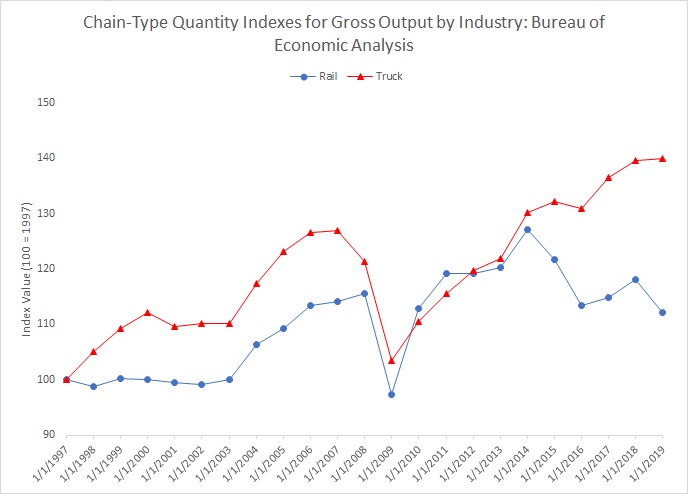

Miller points to the rail and truck trend lines in Bureau of Economic Analysis figures beginning in 1997. “Looking at these data, rail output was flat from 1997 through 2003 despite truck transportation ticking upward. Rail then had a nice jump in the mid 2000s, which corresponds to the strongest industrial production of manufacturing excluding computers,” he says. “The Great Recession hammered both modes, but rail grew just as rapidly as truck before falling in 2015, which is due to the joint downturn of coal mining and hydraulic fracking. As such, the slower growth seems more a function of the changing nature of economic activity.”

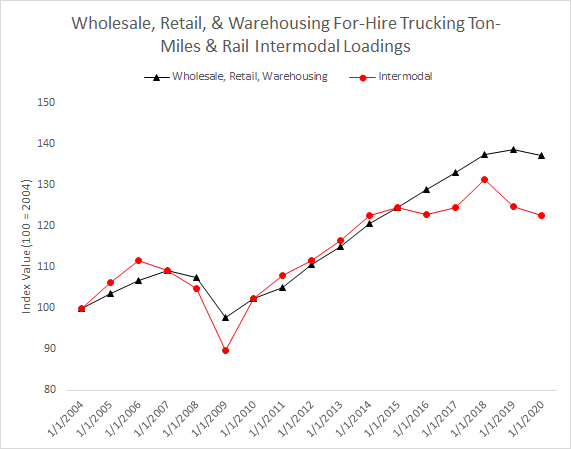

When you break out intermodal separately versus trucks that haul consumer goods, a similar trend emerges. Intermodal grew faster immediately after the Great Recession, and then grew in tandem with trucking until 2015. Then trucks take over.

Miller chalks this up to a couple of trends. Low truck rates in 2016-17 and 2019 diverted intermodal loads back to the roads. Meanwhile, West Coast ports lost market share to East Coast ports, where international containers are far more likely to hit the highway.

East vs. West

If you drill down into trends for carload volume – with carload defined as everything that’s not coal, intermodal, and autos – a huge gap emerges between the East and West. Between 2006 and 2019, carload volume was down 16% in the East and up 5% in the West, according to a Trains review of annual report data from CSX Transportation, Norfolk Southern, BNSF Railway, and Union Pacific.

This suggests a couple of things. First, it shows that economic changes were more profound in the East, where U.S. manufacturing is concentrated. Second, this shows the impact of truck competition, which is more intense in the East due to shorter lengths of haul.

And if Mr. Oberman wants a smoking gun on how an operating ratio focus shows up in traffic figures, he can find it in Fort Worth and Omaha. BNSF has long had a bias for growth, and its carload business was up 12% from 2006 through 2019. UP has long emphasized profit margins over volume growth, and its carload traffic was down 1%.

A Cause for Concern

Whatever the causes, the overall carload and intermodal trend lines concern many industry observers.

“It is clear that rail carriers have lost market share to trucks over the last five years and the ongoing service issues threaten to increase that shift,” says Todd Tranausky, vice president of rail and intermodal at freight forecasting firm FTR Transportation Intelligence. “The question is what the carriers are going to do about it?”

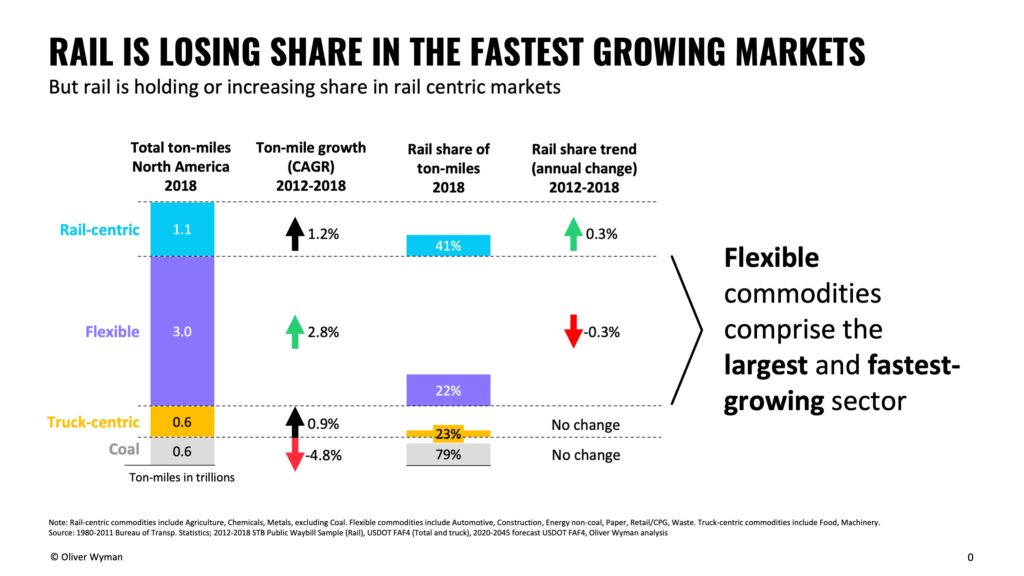

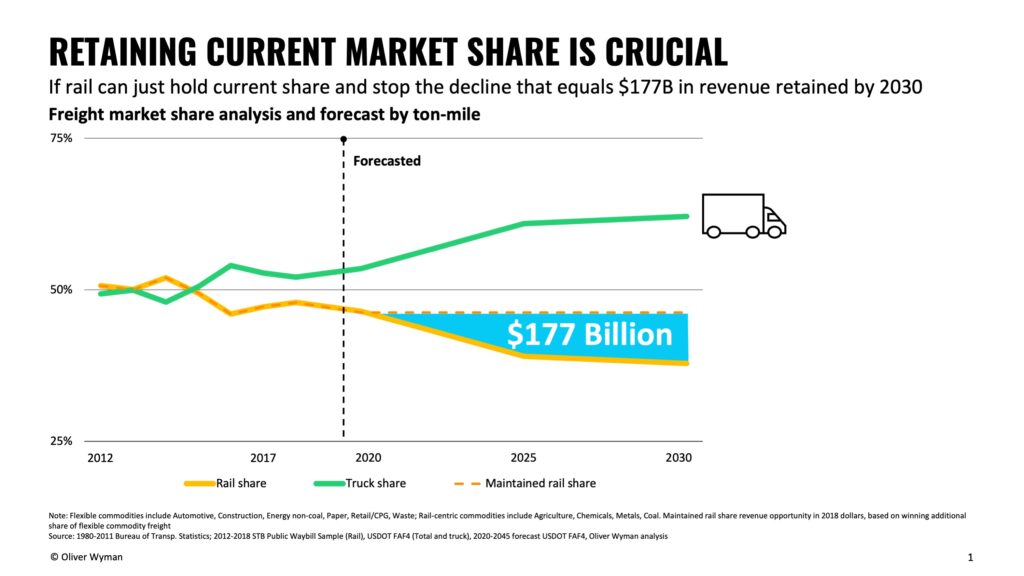

A study by consulting firm Oliver Wyman found that rail is losing share in the fastest-growing freight segments, which includes traffic like autos that can move by truck or rail. If the current trends continue, the truck versus rail gap would widen and railroads would lose $177 billion in revenue by 2030. Oliver Wyman concluded that to hang on to volume, railroads would have to become more reliable, provide shipment visibility, and become easy to work with while becoming supply chain partners.

Nick Little, director of railway education at Michigan State’s Center for Railway Research & Education, agrees: “The sooner the Class Is change their culture to think and behave like a key part of their customers’ supply chains, the better chance they will have of helping the nation, and the world, by enabling the switch to rail that Marty Oberman really wants to see as his legacy in his STB role.”

You can reach Bill Stephens at bybillstephens@gmail.com and follow him on LinkedIn and Twitter @bybillstephens

I have seen so many industries that are clear bulk rail shippers turn away from railroads due to awful service and indifferent management in my lifetime (61 years). It’s depressing. In the sort time I worked in the industry it became VERY clear that Class 1s, their management, and the unions just didn’t care about their customers.

Shortlines and contract switchers were clearly and obviously a step above the big boys in service in every way. Their biggest problem? Class 1s, their management, and unions.

If Class 1s were serious about expanding their market share, they would hire shortlines to switch and service customers on their lines by paying them per car, car mile, or ton mile. The Class 1s could then do what they do best – move whole trains from point A to point Z, and allow the smaller companies to handle all that aggravating stuff from points B to Y.

The biggest issue would be home the Class 1s would handle the sudden and significant doubling of their market share in only 2-3 years.

As a truck driver this has nothing to do with the decline in traffic, one there’s a huge shortage of drivers, and two there’s way to many regulations that scare many off of encourage a job change.

Don’t know where to begin. RR companies have been harvesting profits for years while ignoring the last mile problem. Amazon built a huge truck network ignoring rail sidings everywhere meanwhile RR tore up millions of miles of track. So short term. Carbon tax might make people think of the true cost.

An article in ‘Trains’ a few months ago pointed out a basic problem, the long delays in answering a potential customer’s inquiries. Other railroads were amazed the BNSF and CSX would get back to a customer within a day. Like other employees the roads have been firing salespeople.

Most customers don’t buy in 2 mile long train load lots even if they are Amazon. But railroads are going the other way. By the way, when we tried to buy box car loads of plaster from Oklahoma to New England it was’t just the first and last mile that were slow it was the whole thing, and it wasn’t that much cheaper than trucks.

Try to get plastic pellets out of the petro coast to your plant in Wisconsin. Oh, your land locked siding only holds 4 covered hoppers? So sad for you, your switching fee just doubled because we only allow a minimum of 8 cars and we are going to charge you for those 4 extra cars to sit in our yard. And we won’t guarantee *anything*.

This is why more and more grain elevator companies are building their own sidings and owning their own hoppers and even their own hi-rail switcher.

Also, notice intermodal losing market share after 2015? I retired in 2016.

Blame me!

It would also be useful if RRs would think about where they want to be in 15-20 years and start heading there.

I would think mainline electrification and an as-yet-to-be created second generation ECP system would top the list.

Increased overall velocity and reduced operating costs would allow greater market penatration.

Forget carload. It’s a boutique product. The first and last mile are far too slow (and costly). Intermediate handling/classification make the linehaul trip way too slow.

Instead, focus on increasing speed and reducing cost of intermodal to become more valuable in more lanes.

NS uses 8 crews to get from NJ to Memphis because route is slow. High cost and low speed are losing combo.

You don’t have raise MAS to speed up service. Just smooth out route to keep things moving.

NS has 60 MAS for all intermodal yet can do NJ to Chicago – nearly as far as NJ – Memphis – with four crews. Guess which lane has higher market penetration?

This is an excellent piece.

My opinion is RRs stopped trying to develop intermodal growth. Have NS or CSX really done anything but talk about the I-85/95 and Crescent Corridors?

No.

Chasing OR to buy back stock is a going-out-of-business strategy. They should at least be honest about it.

It’s not solely on the railroads here…there’s another part of the supply chain that could change back to old ways too, and that’s warehousing. Or even retailers like Costco and Sam’s Club, both of those should be rail served facilities and be ordering their major products by the carload. Imagine the savings a retailer could pass along if they bought carloads of commodities directly from the manufacturers, of course that would cut out middle men, warehousing and distribution costs(and related jobs, but those would be offset by having them in-house, and you could provide delivery right to the consumers door.

Gerald — Many of the distribution centers spring up like oversized mushrooms are near railroads – not because of rail service but because of industrial zoning in those areas. I’ve yet to see one with a rail spur.

Everyone reading these comments knows what I’m talking about – Amazon or whomever served by COFC handled from the container lift over the highways, adding to highway congestion. Fifty truck docks, zero rail spurs.