To read Part I of George Drury’s New York Central History, click here

History of the New York Central System

The New York Central was a large railroad, and it had several subsidiaries whose identity remained strong, not so much in cars and locomotives carrying the old name but in local loyalties: If you lived in Detroit, you rode to Chicago on the Michigan Central, not the New York Central; through the Conrail era and even now, the line across Massachusetts is still known as “the Boston & Albany.”

The system’s history is easier to digest in small pieces: first New York Central followed by its two major leased lines, Boston & Albany and Toledo & Ohio Central; then Michigan Central and Big Four (Cleveland, Cincinnati, Chicago & St. Louis). By the mid-1960s NYC owned 99.8 percent of the stock of Michigan Central and more than 97 percent of the stock of the Big Four. NYC leased both on Feb. 1, 1930, but they remained separate companies to avoid the complexities of merger.

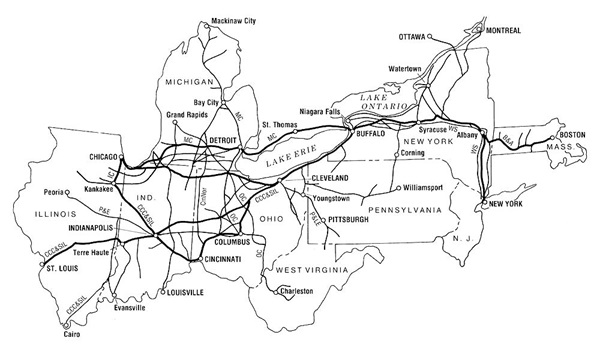

In broad geographic terms, the NYC proper was everything east of Buffalo plus a line from Buffalo through Cleveland and Toledo to Chicago (the former Lake Shore & Michigan Southern). NYC included the Ohio Central Lines (Toledo through Columbus to and beyond Charleston, W.Va.) and the Boston & Albany (neatly defined by its name). The Michigan Central was a Buffalo–Detroit–Chicago line and everything in Michigan north of that. The Big Four was everything south of NYC’s Cleveland–Toledo–Chicago line other than the Ohio Central.

The New York Central System included several controlled railroads that did not accompany NYC into the Penn Central merger. The most important of these were (with the proportion of NYC ownership in the mid-1960s):

• Pittsburgh & Lake Erie (80 percent)

• Indiana Harbor Belt (NYC, 30 percent; Michigan Central, 30 percent; Chicago & North Western, 20 percent; and Milwaukee Road, 20 percent)

• Toronto, Hamilton & Buffalo (NYC, 37 percent; MC, 22 percent; Canada Southern, 14 percent; and Canadian Pacific, 27 percent).

West Shore

During 1869 and 1870 several railroads were proposed and surveyed up the west bank of the Hudson River. In 1880 the New York, West Shore & Buffalo Railroad was formed to build a line from Jersey City to Albany and Buffalo, parallel to the New York Central. William Vanderbilt suspected (correctly) that the Pennsylvania Railroad was behind the project. The new road opened to Buffalo in 1884. A rate war ensued, bankrupting the West Shore.

In retaliation Vanderbilt decided to revive an old survey for a railroad across Pennsylvania that was considerably shorter than the Pennsylvania Railroad. He enlisted the support of Andrew Carnegie and John D. Rockefeller.

It took J. P. Morgan to work a compromise between the NYC and the Pennsylvania: The Central would lease the West Shore, and the Pennsy would get the South Pennsylvania and its partially excavated tunnels. In 1885 the West Shore was reorganized as the West Shore Railroad, wholly owned by the NYC. (The South Penn’s roadbed was later used for the Pennsylvania Turnpike.) The Weehawken–Albany portion of the West Shore proved to be a valuable freight route for NYC and its successors. Most of the West Shore west of Albany has been abandoned.

Ohio Central Lines

Ohio Central Lines included the Toledo & Ohio Central Railway and three leased lines, the Zanesville & Western, the Kanawha & Michigan, and the Kanawha & West Virginia. They formed a route from Toledo southeast through Columbus, across the Ohio River, and through Charleston to Hitop, W.Va. The Ohio Central began as the Atlantic & Lake Erie, chartered in 1869. After a series of receiverships and a name change to Ohio Central, the road managed to link Columbus with the Ohio River at Middleport in 1882. It then pushed into the coalfields along the Kanawha River in West Virginia and extended itself northwest toward Toledo. It was renamed the Toledo & Ohio Central in 1885.

The NYC acquired control of the T&OC by 1910 and began operating it as part of the New York Central System. NYC leased the road in 1922 and merged it in 1952.

J. David Ingles

Michigan Central

Michigan Central had its beginnings in the Detroit & St. Joseph Railroad, which was incorporated in 1832 to build a railroad across Michigan from Detroit to St. Joseph. Michigan attained statehood in 1837 and almost immediately chartered railroads to be constructed along three routes: the Northern, from Port Huron to the head of navigation on the Grand River; the Central, from Detroit to St. Joseph; and the Southern, from the head of navigation on the River Raisin to New Buffalo.

Michigan Central had its beginnings in the Detroit & St. Joseph Railroad, which was incorporated in 1832 to build a railroad across Michigan from Detroit to St. Joseph. Michigan attained statehood in 1837 and almost immediately chartered railroads to be constructed along three routes: the Northern, from Port Huron to the head of navigation on the Grand River; the Central, from Detroit to St. Joseph; and the Southern, from the head of navigation on the River Raisin to New Buffalo.

The state purchased the Detroit & St. Joseph to use as the basis for the Central Railroad. About the time the road reached Kalamazoo in 1846 it ran out of money. It was purchased from the state by Boston interests and was reorganized as the Michigan Central Railroad. Construction resumed in the direction of New Buffalo rather than St. Joseph, and in 1849 the line reached Michigan City, Ind., about as far as its Michigan charter could take it.

To reach the Illinois border the Michigan Central used the charter of the New Albany & Salem (a predecessor of the Monon) in exchange for which it purchased a block of NA&S stock. The MC continued on Illinois Central rails to Chicago, reaching there in 1852.

Vanderbilt began buying MC stock in 1869, and NYC leased the road in 1930.

The Great Western Railway opened in 1854 from Niagara Falls to Windsor, Ont., opposite Detroit. In 1855 John Roebling’s suspension bridge across the Niagara River was completed, creating with the NYC a continuous line of rails from Albany to Windsor. The 5-foot 6-inch Great Western installed a third rail for standard gauge equipment during 1864–66.

Vanderbilt tried without success to purchase the Great Western and turned his attention to the Canada Southern. It had been incorporated in 1868 as the Erie & Niagara Extension Railway to build a line along the north shore of Lake Erie and then across the Detroit River below the city of Detroit. He acquired the Canada Southern in 1876, and Michigan Central leased it in 1882. New York Central leased the Michigan Central in 1930.

Cleveland, Cincinnati, Chicago & St. Louis (Big Four)

The oldest predecessor of the Big Four (and a comparatively late addition to it) was the Mad River & Lake Erie. Ground was broken in 1835, and the line opened from Sandusky to Dayton, Ohio, in 1851. It went through several renamings and became part of what later was the Peoria & Eastern before it was merged into the CCC&StL in 1890.

The Cleveland, Columbus & Cincinnati got its charter in 1836, broke ground in 1847, and opened in 1851 between Cleveland and Columbus. In 1852 it teamed up with the Little Miami and Columbus & Xenia railroads to form a Cleveland–Cincinnati route.

In 1848 the Indianapolis & Bellefontaine and the Bellefontaine & Indiana railroads were incorporated to build a line between Galion, Ohio, on the CC&C, and Indianapolis. The I&B and the B&I amalgamated and became known as “The Bee Line.” They were absorbed by the CC&C when it reorganized as the Cleveland, Columbus, Cincinnati & Indianapolis in 1868.

The CCC&I reached Cincinnati with its own rails in 1872. That same year it opened a line from Springfield to Columbus. By then the Vanderbilts owned a good portion of the road’s stock.

The Terre Haute & Alton Railroad was organized in 1852. Its backers were certain that with a railroad to Indiana the Mississippi River town of Alton, Ill., could easily outstrip St. Louis a few miles south. It soon combined with the Belleville & Illinoistown Railroad (Illinoistown is now East St. Louis) as the Terre Haute, Alton & St. Louis. The Indianapolis & St. Louis was organized to build between Indianapolis and Terre Haute. It leased the St. Louis, Alton & Terre Haute, successor to the Terre Haute, Alton & St. Louis, and came under control of the CCC&I in 1882.

In the late 1840s and early 1850s several railroads were completed forming a route from Cincinnati through Indianapolis and Lafayette, Ind., to Kankakee, Ill., connecting there with the Illinois Central north to Chicago. In 1880 these roads were united as the Cincinnati, Indianapolis, St. Louis & Chicago — which some consider the first “Big Four.” Heading the company was Melville Ingalls, and on its board was C. P. Huntington, whose Chesapeake & Ohio formed a friendly connection at Cincinnati.

The Vanderbilts had invested in the first Big Four, and they were firmly in control of the second Big Four, the Cleveland, Cincinnati, Chicago & St. Louis, which was formed in 1889 by the consolidation of the old Big Four (Cincinnati, Indianapolis, St. Louis & Chicago) and the Bee Line (Cleveland, Columbus, Cincinnati & Indianapolis).

In the late 1880s Ingalls and the Vanderbilts gathered in a group of railroads between Cairo and Danville, Ill.; added to them the St. Louis, Alton & Terre Haute, then added them all to the Big Four. The line from Danville north to Indiana Harbor was a comparatively late addition to the system: It was built in 1906 and became part of the New York Central rather than the Big Four.

The Peoria & Eastern was formed in 1890 from several small roads. At one time its predecessor briefly included the former Mad River & Lake Erie and a line from Indianapolis east to Springfield, Ohio, before settling down to be simply a Peoria–Bloomington–Danville–Indianapolis route.

In 1902 the Big Four bought the Cincinnati Northern, a line that had been proposed in 1852 and finally constructed in the 1880s from Franklin, Ohio, between Dayton and Cincinnati, to Jackson, Mich.

In 1920 the Big Four acquired the Evansville, Indianapolis & Terre Haute, a castoff from the Chicago & Eastern Illinois in southwestern Indiana. The New York Central leased the Big Four in 1930.

C. W. Jernstrom

New York Central System

The New York Central System was the largest of the eastern trunk systems from the standpoint of mileage and second only to the Pennsylvania in revenue. It served most of the industrial part of the country, and its freight tonnage was exceeded only by the coal-carrying railroads. In addition it was a major passenger railroad, with perhaps two-thirds the number of passengers as the Pennsylvania, but NYC’s average passenger traveled one-third again as far as Pennsy’s. NYC did not share as fully in the post-World War II prosperity because of rising labor costs, material costs, and an expensive improvement program, especially for passenger service.

During 1946–47 Chesapeake & Ohio purchased a block of NYC stock, becoming the road’s largest stockholder. Robert R. Young gained control of the Central and became its chairman in 1954 as part of a maneuver to merge it with C&O. One of his first acts was to put Alfred E. Perlman in charge of the NYC.

Under Perlman NYC slimmed its physical plant, reducing long stretches of four-track line to two tracks under centralized traffic control, and developed an aggressive freight marketing department. At the same time NYC’s passenger operations were de-emphasized. On December 3, 1967, just before NYC and Pennsy merged, the Central reduced its passenger service to a skeleton, combining its New York–Chicago, New York–Detroit, New York–Toronto, and Boston–Chicago services into a single train and dropping all train names (including that of the legendary 20th Century Limited) except for, curiously, that of the Chicago–Cincinnati James Whitcomb Riley.

The Central’s archrival was the Pennsylvania Railroad. West of Buffalo and Pittsburgh the two systems duplicated each other at almost every major point; east of those cities the two hardly touched. Both had physical plant not being used to capacity (NYC was in better shape); both had a heavy passenger business; neither was earning much money. In 1957 NYC and Pennsy announced merger talks.

The initial industry reaction was utter surprise. Every merger proposal for decades had tried to balance the Central against the Pennsy and create two, three, or four more-or-less-equal systems in the east. Traditionally PRR had been allied with Norfolk & Western and Wabash; NYC with Baltimore & Ohio, Reading, and maybe the Lackawanna; and everyone else swept up with Erie and Nickel Plate. Tradition also favored end-to-end mergers rather than those of parallel roads.

Planning and justifying the merger took nearly ten years, during which time the eastern railroad scene changed radically, in large measure because of the impending merger of NYC and PRR: Erie merged with Lackawanna, C&O acquired control of B&O, and N&W took in Virginian, Wabash, Nickel Plate, Pittsburgh & West Virginia, and Akron, Canton & Youngstown.

Tradition aside, though, the New York Central and the Pennsylvania merged on Feb. 1, 1968 to form Penn Central.

Robert Young was Chairman of the C&O and wanted to merge the Central with the C&O. Once Young left, the C&O no longer wanted to merge with the Central.