John P. Ahrens

To read Part 2 of George Drury’s New York Central history, click here

History of the New York Central System

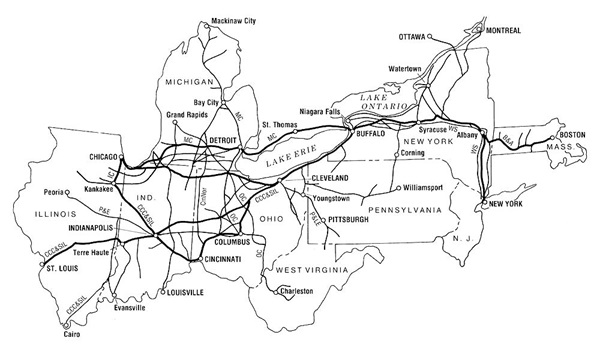

The New York Central was a large railroad, and it had several subsidiaries whose identity remained strong, not so much in cars and locomotives carrying the old name but in local loyalties: If you lived in Detroit, you rode to Chicago on the Michigan Central, not the New York Central; through the Conrail era and even now, the line across Massachusetts is still known as “the Boston & Albany.”

The system’s history is easier to digest in small pieces: first New York Central followed by its two major leased lines, Boston & Albany and Toledo & Ohio Central; then Michigan Central and Big Four (Cleveland, Cincinnati, Chicago & St. Louis). By the mid-1960s NYC owned 99.8 percent of the stock of Michigan Central and more than 97 percent of the stock of the Big Four. NYC leased both on Feb. 1, 1930, but they remained separate companies to avoid the complexities of merger.

The system’s history is easier to digest in small pieces: first New York Central followed by its two major leased lines, Boston & Albany and Toledo & Ohio Central; then Michigan Central and Big Four (Cleveland, Cincinnati, Chicago & St. Louis). By the mid-1960s NYC owned 99.8 percent of the stock of Michigan Central and more than 97 percent of the stock of the Big Four. NYC leased both on Feb. 1, 1930, but they remained separate companies to avoid the complexities of merger.

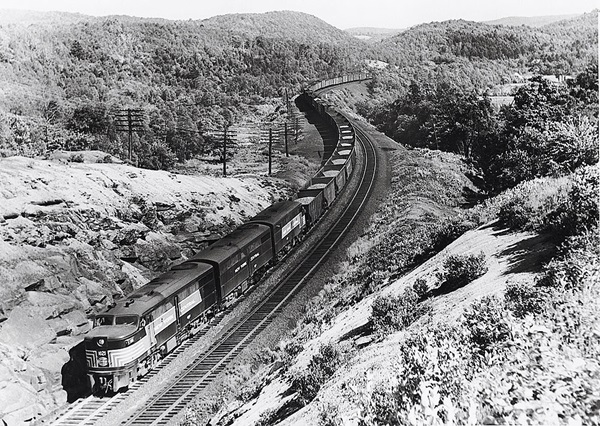

In broad geographic terms, the NYC proper was everything east of Buffalo plus a line from Buffalo through Cleveland and Toledo to Chicago (the former Lake Shore & Michigan Southern). NYC included the Ohio Central Lines (Toledo through Columbus to and beyond Charleston, W.Va.) and the Boston & Albany (neatly defined by its name). The Michigan Central was a Buffalo–Detroit–Chicago line and everything in Michigan north of that. The Big Four was everything south of NYC’s Cleveland–Toledo–Chicago line other than the Ohio Central.

The New York Central System included several controlled railroads that did not accompany NYC into the Penn Central merger. The most important of these were (with the proportion of NYC ownership in the mid-1960s):

• Pittsburgh & Lake Erie (80 percent)

• Indiana Harbor Belt (NYC, 30 percent; Michigan Central, 30 percent; Chicago & North Western, 20 percent; and Milwaukee Road, 20 percent)

• Toronto, Hamilton & Buffalo (NYC, 37 percent; MC, 22 percent; Canada Southern, 14 percent; and Canadian Pacific, 27 percent).

R. E. Tobey

New York Central

The Erie Canal, opened in 1825 between Albany and Buffalo, followed the Hudson and Mohawk rivers between Albany and Schenectady. The 40-mile Albany–Schenectady water route included several locks and was slow; in consequence, stagecoaches plied the 17-mile direct route between the cities. In 1826 the Mohawk & Hudson Rail Road was incorporated to replace the stages between Albany and Schenectady.

The Mohawk & Hudson opened in 1831; its first locomotive was named DeWitt Clinton after the governor of the state when the M&H was incorporated. Within months there was a proposal for a railroad all the way from Albany to Buffalo.

One by one, railroads were incorporated, built, and opened westward from the end of the Mohawk & Hudson: Utica & Schenectady, Syracuse & Utica, Auburn & Syracuse, Auburn & Rochester, Tonawanda (Rochester to Attica via Batavia), and Attica & Buffalo. By 1841 it was possible to travel between Albany and Buffalo by train in just 25 hours, lightning speed compared with the canal packets. Ten years later the trip took a little over 12 hours. In 1851 the state passed an act freeing the railroads from the need to pay tolls to the Erie Canal, with which they competed. That same year the Hudson River Railroad opened from New York to East Albany.

From the beginning the railroads between Albany and Buffalo had cooperated in running through service. In 1853 they were consolidated as the first New York Central Railroad — the roads mentioned above or their successors plus the Schenectady & Troy; the Buffalo & Lockport; the Rochester, Lockport & Niagara Falls; and two unbuilt roads, the Mohawk Valley and the Syracuse & Utica Direct.

The New York & Harlem Railroad was incorporated in 1831 to build a line in Manhattan from 23rd Street north to 129th Street between Third and Eighth avenues (the railroad chose to follow Fourth Avenue). At first the railroad was primarily a horsecar system, but in 1840 the road’s charter was amended to allow it to build north toward Albany. In 1844 the rails reached White Plains and in January 1852 the New York & Harlem made connection with the Western Railroad (later Boston & Albany) at Chatham, N.Y., creating a New York–Albany rail route.

The towns along the Hudson River felt no need of a railroad, except during the winter when ice prevented navigation. Poughkeepsie interests organized the Hudson River Railroad in 1847. The railroad opened from a terminal on Manhattan’s west side all the way to East Albany. By then the road had leased the Troy & Greenbush, gaining access to a bridge over the Hudson at Troy. (A bridge at Albany was completed in 1866.)

By 1863 Cornelius Vanderbilt controlled the New York & Harlem and had a substantial interest in the Hudson River Railroad. In 1867 he obtained control of the New York Central, consolidating it with the Hudson River in 1869 to form the New York Central & Hudson River Railroad.

Vanderbilt wanted to build a magnificent terminal for the NYC&HR in New York. He chose as its site the corner of 42nd Street and Fourth Avenue on the New York & Harlem, the southerly limit of steam locomotive operation in Manhattan. Construction of Grand Central Depot began in 1869. The new depot was actually three separate stations serving the NYC&HR, the New York & Harlem, and the New Haven. Trains of the Hudson River line reached the New York & Harlem by means of a connecting track completed in 1871 along Spuyten Duyvil Creek and the Harlem River (they have since become a single waterway). That was the first of three Grand Centrals.

The present station, Grand Central Terminal, was opened in 1913. Even today Grand Central remains awesome. GCT has a total of 48 platform tracks on two subterranean levels; the project included depressing and decking over the tracks along Park Avenue and electrifying NYC’s lines north to Harmon and White Plains. (NYC had two other electrified segments: the Detroit River Tunnel, opened in 1910, and Cleveland Union Terminal, opened in 1930. Diesels put an end to both those electrifications in 1953.)

The Watertown & Rome Railroad was chartered in 1832 to connect Watertown, N.Y., with the Syracuse & Utica (then only a proposal itself). The road opened in 1851, and in 1852 it was extended to Cape Vincent, where it connected with a ferry to Kingston, Ontario. In 1861 the W&R consolidated with the Potsdam & Watertown to form the Rome, Watertown & Ogdensburg. The RW&O built a line to Oswego and bought lines to Syracuse and Buffalo. The line to Buffalo was a mistake — it bypassed Rochester, had almost no local business, and was not part of any through route.

The RW&O came under Lackawanna control briefly before a rehabilitation in the 1880s. New management extended the RW&O north to connect with a Grand Trunk line to Montreal and added the Black River & Utica (Utica to Watertown and Ogdensburg) to the system. NYC leased the RW&O in 1893.

Meanwhile, NYC had built its own line north from Herkimer: the St. Lawrence & Adirondack (later Mohawk & Malone). NYC merged the Mohawk & Malone in 1911 and the RW&O in 1913.

Lake Shore & Michigan Southern

The Michigan Southern was chartered by the state of Michigan in 1837 to build across the southern tier of Michigan to Lake Michigan. Under state auspices it got as far west as Hillsdale, Mich. It was sold to private interests which combined it with the Erie & Kalamazoo (opened in 1837 from Toledo to Adrian, Mich.) and extended it west to meet the Northern Indiana Railroad, which was building east from La Porte, Ind. The line opened from Monroe to South Bend in 1851; by February 1852 it reached Chicago, where it teamed up with the Rock Island to build terminal facilities. (Its successors shared a Chicago station, La Salle Street, with Rock Island until 1968). The roads were combined as the Michigan Southern & Northern Indiana in 1855. By then a direct line between Elkhart, Ind., and Toledo had been built.

The railroad situation along the south shore of Lake Erie was complicated by Ohio’s insistence on a track gauge of 4 feet 10 inches, Pennsylvania’s reluctance to let a railroad from another state cross its borders, and the desire of the city of Erie, Pa., to have the change of gauge within its limits in the hope that passengers would spend money while changing trains there.

The NYC controlled the Buffalo & State Line and the Erie & North East railroads by 1853; they were combined as the Buffalo & Erie in 1867. The Cleveland, Painesville & Ashtabula was opened between Cleveland and Erie in 1852. In 1868 the CP&A took its familiar name, Lake Shore, as its official name, and a year later it absorbed the Cleveland & Toledo and joined with the Michigan Southern & Northern Indiana to form the Lake Shore & Michigan Southern. During a business panic about that time, Cornelius Vanderbilt acquired control of the LS&MS.

In 1914 the New York Central & Hudson River, the Lake Shore & Michigan Southern, and several smaller roads were combined to form the New York Central Railroad — the second railroad of that name.

New York Central

Boston & Albany

The Boston & Worcester Railroad opened between the cities of its name in 1835. Its charter had a clause prohibiting the construction of a parallel railroad within 5 miles for 30 years. The Western Railroad opened in 1840 from Worcester west to Springfield and in 1841 across the Berkshires to Greenbush, N.Y., on the east bank of the Hudson opposite Albany. The two railroads shared some directors, but efforts at merging them were futile until 1863, when B&W’s protection clause expired and the Western proposed building its own line from Worcester to Boston. The two roads were consolidated as the Boston & Albany Railroad in 1867.

The B&A had several minor branches and a few major ones: Palmer to Winchendon, Mass., Springfield to Athol, Mass., Pittsfield to North Adams, Mass.; and Chatham to Hudson, N.Y.

The B&A’s principal connection was the New York Central at Albany, and in 1900 the NYC leased the B&A. The Central wanted a route to Boston. It had a choice of the B&A or the parallel Fitchburg Railroad (later Boston & Maine). If NYC chose the Fitchburg, the B&A would be left with only local business, so B&A willingly forsook independence. In 1961 NYC merged the Boston & Albany.

B&A maintained more of its identity than other NYC subsidiaries. It had its own officers, and until 1951 its locomotives and cars were lettered “Boston & Albany” rather than “New York Central Lines.” B&A’s steam power was basically of NYC appearance but with a few distinctive features, such as square sand domes on the Hudsons and offset smokebox doors on Pacifics. The profile of the B&A, definitely not the water level route NYC was so proud of elsewhere, called for heavy power in the form of 2-6-6-2s and 2-8-4s (the latter named for the Berkshires over which the line ran). Nearer Boston, B&A ran an extensive suburban service.

To read Part 2 of George Drury’s New York Central history, click here

I had a mentor in my young RR life by the name of PM Pat Miller.

He was in charge of water quality NYC system wide during WWII. Both for

locos, steam generators on diesels and depot heating systems. Needless to say

I learned a lot about the inside workings of NYC. He was an excellent photographer

and I have some of his collection. Some being the initial run of the Empire State

Express, on December 7, 1941. Too much to tell here.