Car trucks and carbodies

Do you remember running boards and full-height ladders on box cars? They are known in the railway supply trade as freight-car components, and while running boards and full-height ladders have followed the telegraph key and the steam locomotive into railroad technological history, other components remain as key elements of the freight cars you see on today’s trains.

What most people think of when they hear the word “freight car” is the boxcar. Although boxcars come in different sizes and shapes (and with a variety of options depending upon the service) they all share the three major components of all freight cars: Trucks, carbody, and safety appliances.

Trucks and wheel bearings

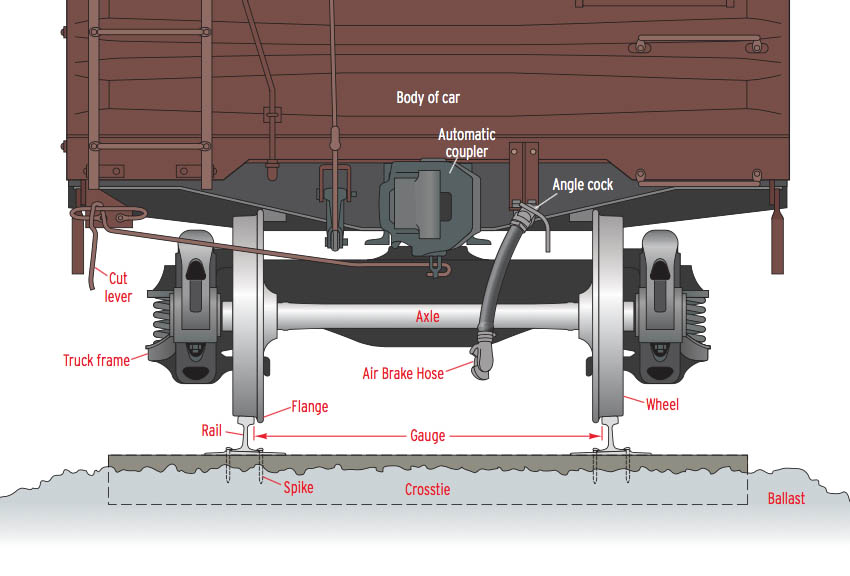

A boxcar rides on two trucks (called “bogies” on overseas railways). Each is a 9,000-pound assembly of individual components (including, but not limited to, axles, wheels, and truck side frames) held together only by gravity and the interlocking surfaces on the principal parts.

The purpose of the truck is to provide support, mobility, and guidance for the car. Like their model railroad counterparts, freight-car trucks are a separate unit that can be removed for maintenance, repair, or replacement.

A common reason for truck removal is to service journal bearings, the general term used to describe the load-bearing arrangement at the ends of each axle of the truck. There are two types of journal bearings found on U.S. freight-car trucks: friction bearings (also referred to as plain journal bearings) and roller bearings.

Friction bearings consist of blocks of metal, usually brass, resting atop the axle and lubricated by oil-saturated wool waste enclosed in a hinged-lid journal box. While the friction bearing is an excellent design in terms of efficiency (one person using only a jack can replace a friction bearing in about three minutes), it lacks sufficient ability to dissipate heat under adverse conditions, such as in high-speed service, and requires frequent attention.

When a hot-box detector (a trackside device that takes heat readings off passing trains and transmits a simulated voice message by radio to the train’s engineer) announces that a train has “no defects,” it means that a failed bearing hasn’t caused friction to heat the end of the axle to a dangerous point. When this occurs the steel is so weakened that the weight of the car breaks it off, dropping the truck frame to the roadbed and causing a disaster similar to the model railroad pileups that used to bring a devilish smile to the face of Gomez Addams on the old “Addams Family” TV show. Friction bearings are particularly sensitive to this particular malfunction, which is known as a “hot box.” Note: some trackside detectors, equipped for more than heat readings, are called “dragging equipment detectors,” or “draggers.”

Roller bearings have been the bearing of preference since 1963, when they became required on all new freight cars. The principal advantage of roller bearings over friction bearings is reduced maintenance, in that the latter must be visually inspected by opening the journal box lid to verify the condition of the bearing. Although it’s rare to find a car equipped with friction bearings on most U.S. freight trains, they are found on older equipment, including maintenance of way equipment and even some cabooses.

The wheels on a box car are of either cast or forged steel in one of three types (class A, B, or Q representing an increasingly higher carbon content. A 70-ton box car (which has a nominal car capacity of 70 tons) travels on 33-inch diameter wheels; larger 100- and 125-ton cars, concurrent with higher carrying capacities, sport 36and 38-inch diameter wheels.

The wheels are mounted on steel shafts called axles. Each axle (two on both of our four-wheel trucks) holds the wheels to the width of the track gauge (standard gauge is 4 feet, 8-1/2 inches). They also transmit the load from the journal bearings to the wheels. The axles are forged from medium carbon steel and weigh as much as 1,200 pounds.

Both trucks are connected to a center sill, which is basically the backbone of the carbody. You won’t normally see the center sill unless a car is off of the tracks and tipped over. The center sill also connects the pockets for the draft gear and coupler assemblies, which transmit the push and pull loads that characterize overall train motion.

Carbodies

A cheap and low-maintenance item — gravity — holds the carbody in place on the trucks. The carbody is designed as a unit with the center sill, creating in effect a load-bearing “bridge” supported only at the center of both trucks.

Most carbodies, including a box car, are built of copper-bearing, low-alloy, high-tensile steel. Aluminum alloy cars (which are lighter, more durable, and more expensive than steel) can be found in specific services such as hauling coal in solid “unit” trains where the higher load capacity of aluminum alloy open-top cars justifies the car’s extra cost. Take note if you’re trackside and spot a freight car with a wooden carbody: They’re now rare, if not extinct, in U.S. railroad revenue service.

Safety appliances

While you’re at it, keep your eye peeled for two other examples of outmoded car components, the roof-mounted running board and the full-height safety ladder.

Running boards are, depending on the car’s construction, wood or steel planking that provide a walking surface along the center of the car roof. In earlier times they were used by trainmen to travel from car to car to control train speed with the car’s hand brakes — not an exercise for the faint-hearted.

With the development of the air brake (which allowed the engineer to control the train’s speed from the locomotive), running boards were mainly used by trainmen to pass hand or lantern signals to the engine crew.

The advent of radio communication killed off this hazardous practice, though, and today it is expressly forbidden for crew members to go atop cars in motion, thus eliminating the need for running boards and the full-height safety ladders at the ends of the cars needed to get to them. Today you’ll only see these components on newer cars such as covered hopper cars to allow access to loading and unloading operations.

Depending on the specific service it has been designed for, a modern box car probably sports a number of components never thought of back in 1893 when the Federal Safety Appliance Act decided to standardize ladders and running boards.