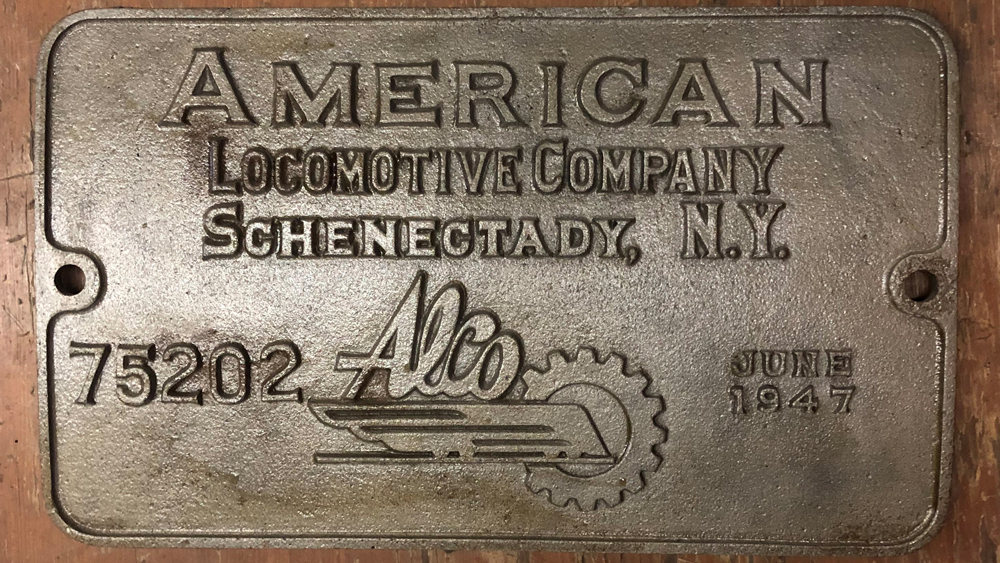

Builder’s plate

Imagine walking around all of your life with your birth certificate attached to your forehead. Anyone could walk up to you and in one glance (assuming they understood your birth certificate’s cryptic codes) ascertain your age, lineage, weight, maybe how many legs you should have, and possibly how much work you can do.

Every locomotive goes through life bearing this information on a builder’s plate — a locomotive’s birth certificate.

Builder’s plates are a locomotive’s record of identity. All of the paperwork in the world can be on file in the office, but the builder’s plate has the final say as to the unit’s identity. Since most locomotives are leased, the builder’s plates (along with the trust plates) are used by lessors to identify their locomotive in a sea of otherwise identical machines.

Where to find them

Locating a locomotive builder’s plate is easy. On steam engines, the plate is high above the cylinders. For diesels and electrics, check out the frame under the cab. Builder’s plates are normally attached to a locomotive on a part that if altered or replaced would change the locomotive’s identity. On steam locomotives, that’s the boiler. On diesels, it’s the frame. For example, a diesel can be stripped to the frame, reassembled with components from another locomotive, and still be the same locomotive as long as the frame isn’t altered. In the birth certificate analogy, that means your head could be grafted to an elephant’s body and it would still be you.

What they tell you

Like a birth certificate, builder’s plates often use codes to pack a lot of information into a limited amount of space.

All true builder’s plates have two basic pieces of information:

- The date the locomotive was built.

- The locomotive’s serial number, assigned in various types of series by each builder.

Some builder’s plates have more information than the basics, including wheel arrangement, weight, and horsepower. Builder’s plates on diesel locomotives built by the Electro-Motive Division (EMD) of General Motors carry the most information. Most steam locomotives and older diesels carried the bare minimum.

The builder’s plates on EMD products are the most fun to read, especially the portion that lists the wheel arrangement. EMD uses the Whyte locomotive classification system created for steam locomotives. This system consists of numbers separated by hyphens. The first digit is the number of wheels in the pilot truck, the middle digit or digits indicates the number of driving wheels, and the final digit relates to the number of trailing-truck wheels. This means that a C-C trucked SD45 in the EMD vernacular is an 0-6-6-0. Even more peculiar, AIA-AlA E units are 0-6-6-0’s in the EMD builder’s plate world.

Unlike a paper birth certificate, a builder’s plate can be pretty heavy, but consider the size of the baby. Steam locomotive and early diesel plates were sand-cast bronze or iron and weighed several pounds. In the 1950’s, most manufacturers switched to etched aluminum plates. These barely weigh a pound but still have a bulk befitting a locomotive.

A hobby within a hobby, builder’s plate collecting is akin to baseball-card trading, but the cards are just a little heavier. Builder’s plates from Union Pacific’s DDA40X monster “Centennial” diesel No. 6900 will be more collectable for the masses than say a builder’s plate from a retired Southern Pacific GP9. However, to a dyed-in-the-wool SP fan, the GP9 plate may be as treasured as the 6900’s. It’s like comparing the value of a Bob Uecker baseball card to Milwaukee Braves fans and that of a Mickey Mantle card to all baseball-card collectors. Builder’s plates from retired E and F units are prized by builder’s-plate collectors because of these engines’ longtime popularity. Like any collectible, the older the plate, the more valuable it may be. Plates from long-defunct diesel builders such as Baldwin, Fairbanks-Morse, and Lima are the most scarce.

If you want to collect builder’s plates, perhaps the best place to start is by buying them at railroadiana meets. The people selling plates at meets often work with railroad scrappers to obtain plates legally. Or, watch the railroad-magazine classifieds for ads from established collectors who might be thinning their collections or otherwise offering plates for sale or trade. If you must obtain a plate first-hand, do it only from locomotives in a scrapper’s yard, and get a receipt. But removing a plate isn’t easy. Screws and rivets are used to attach them to the frame, and 20 to 30 years of dirt and grime makes a powerful adhesive. But at least you don’t have to go down to the courthouse to look at the birth certificate.

Note we said “legally.” Removing a builder’s plate from an in-service locomotive is a federal offense – a felony.

- You can also find some online. Just do your research and buy from a reputable seller.

- The Kalmbach Hobby Store sells a small pin version of a builder’s plate.

- Want to know more about the building blocks of railroading, check out more articles in our ABC’s Of Railroading section.