“Imagine it’s 1905 and we’re photographers in San Francisco. We know the earthquake is coming — what do we want to have on film before it’s gone?”

It was spring 1985 and a group of railroad photographers were pondering the pending “slam-dunk” Southern Pacific-Santa Fe merger with Dick Steinheimer. Documenting the last gasp of independence for the Far West’s flagship carriers was beyond any one person. How could we collectively tackle such a chore? In his characteristically unconventional, perfectly sensible manner, “Stein” had the answer.

On June 4, 1985, David Styffe and I were exploring SP’s San Francisco peninsula service, an operation days away from public takeover. After a full day of trains, we walked into the San Jose station and were presented with the riveting scene of a mother and son absorbing the action through depot windows.

The earthquake was coming — thanks to Richard Steinheimer, we got there just in time.

My discovery of Steinheimer’s photography came around the same time that I was realizing that photography was a skill and not just a combination of luck and equipment purchasing power. We never met — something that I will forever regret— but he taught me. His books serve as touchstones, source material, photographic bibles filled with parables and lessons. My love of strong and creative framing, my appreciation of the complete scene, my passion for black-and-white imagery can all be traced to Steinheimer’s influence. Yet it is a subtler idea that has left a lasting impression on me. Stein showed me that railroad photography could go beyond the locomotive and the train, that it could be about the places instead of the objects. My aesthetic has continued to grow and shift, but this love of location — a love cemented by Stein’s example — has persisted to become one of my deepest photographic values.

I moved to California in 1989, and as result of Stein’s work I was keenly interested in photographing Southern Pacific’s operations on Donner Pass. I called him to ask for suggestions, and I was delighted by our conversation. He shared his knowledge freely and was eager to help me; his positive spirit was more helpful in the long run than any specific photographic advice. I’d met with Stein on several occasions, including in the Sierra, and admired his unhindered enthusiasm for the railroad.

Dick Steinheimer’s dedication to unconventional railroad photography enabled me to think “outside the box,” to look beyond the normal, formal portraits of trains to unusual light conditions, movement, industrial and urban landscapes, weather (especially fog, rain, and snow), and people at work. His inspiration can be seen in such photos of mine as this one of the Skytop Lounge cars on the Milwaukee Road’s Afternoon Hiawatha passing. I made the image on the famous passenger train’s last day of operation at Wisconsin Dells in 1970. The view, made at a slow shutter speed, is from the back windows of the Minneapolis-bound train. The blur of the moving eastbound (to Chicago) Skytop car adds excitement to what otherwise would have been a routine picture. In this case, the dreary winter day makes for a more interesting view in the same way that movement and winter augment Stein’s own pictures, which will remain in my memory, forever fresh.

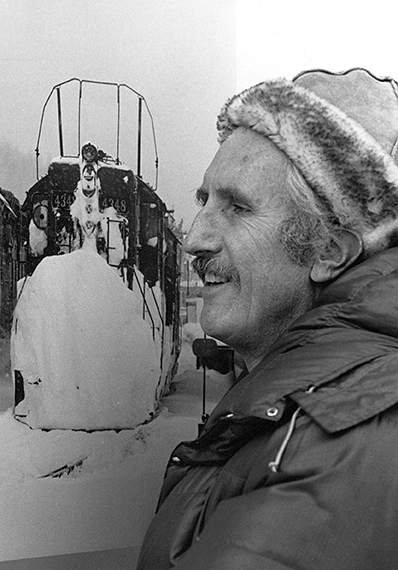

I began photographing trains as I finished high school. At first I took many engine pictures, but about midway through college I began to notice these articles Stein wrote for TRAINS, featuring his photography. I began to think that rail photography was far more interesting than “wedgie” engine photos. About that time, I also acquired a copy of “Backwoods Railroads of the West,” and I simply could not put it down. I almost wore out the dust jacket in the first year or two. This book was the primary motivation to begin shooting black-and-white film, which I have continued to do to this day. It really made me start thinking about composition and lighting and how a photo will look in black and white. It also brought about a total reversal in my ideas about keeping railroaders out of my photos. I realized they were a part of the whole railroad scene. Stein’s photos also inspired me to try creative techniques that I had not done before. Even if I failed on my first try, I kept at it, including taking photos at night. Then a chance meeting with Stein at Norden, Calif., during winter made me think someone else was as crazy as me to want to take pictures in a snowstorm. Sharing our winter experiences on Donner eventually led to our book, “Diesels Over Donner.” This was the ultimate compliment to see my photography featured alongside Stein’s. Even to this day, I can still see how Stein influenced my thoughts about railroad photography.

I’ve spent a lifetime in vain trying to learn how to photograph trains the way Richard Steinheimer once did. Several decades and countless frames of Tri-X, Kodachrome, and JPEGs later, I still enjoy the challenge of capturing any train.

But it was at Ocean Beach in San Francisco one blustery day in 2003 that everything came together for me. I spent a leisurely day in the city with Dick and Shirley Steinheimer, including a spicy Thai lunch, strong coffee in the mid-afternoon, as well as a few trains here and there. We climbed over the sand dunes and tall grass to enjoy a gorgeous view of the Pacific. I took a few snapshots and yelled to them over the roar of the waves, “Stand over there!” CLUNK went the shutter of my enormous Pentax 67. Dick gently turned to Shirley and gave her the sweetest kiss on the forehead. CLUNK. He turned back to me as Shirley looked up at him. CLUNK.

Three frames. Just three frames. But the middle one told the whole story. The story of a man who adored his wife for the incredible woman and partner that she was. And almost presciently, for how much he would appreciate the way she would eventually care for him so lovingly until his last breath.

Like a strobe illuminating a night train, it hit me: all the locomotives, switching yards, and mountain passes I photographed were just dispassionate objects. What made Dick’s photographs so special were the stories he told about the people he captured. All my years of shooting were just practice, culminating in a photograph of my hero and the love of his life.

It was due to Richard Steinheimer’s inspiration and teaching that I was able to capture that moment. Through his photography, he taught me to focus on love. I hope my professor approves.