Importance of The Transcontinental Railroad

In the 1850s, major railroad projects were viewed as projects for the public good, in much the same way we justify public investment in airports and highways. Usually a joint venture between a state or local government and private interests, railroads were expected to generate fair returns for public and private investors, but their ultimate goal was to create a transportation infrastructure that enhanced general prosperity. At the same time, railroad development was undergoing a transformation, moving toward a more speculative and entrepreneurial model where profit and private interests took priority.

The Three Union Pacifics

Envisioned according to older, more cooperative and altruistic standards and expectations, the original Union Pacific emerged in a period of great distress in the U.S. But its speedy completion and efficient operation relied on new business methods and different styles of railroading. The Civil War became a fulcrum in American railroad history, and it necessarily changed what UP was at conception and what it became by the time it was delivered.

Union Pacific and the Central Pacific together worked to build the Transcontinental Railroad, wich was the final — and perhaps, most remarkable — expression of a U.S. railroad as a true public work and national project. The ideals that informed it, the manner of its creation, and the way it was built were characteristic of the earliest days of railroading, projects for the public good.

At the same time, it was Union Pacific one of the first major railroads begun at a point when railroading had adopted a new, compelling, and rather ruthlessly capitalist business model.

Consider the times: The entire economy was being militarized. Men such as J. Edgar Thomson of the Pennsylvania Railroad were revolutionizing and systematizing railroad management. Great sums of money were sloshing about in new and undisciplined ways, which complicated otherwise ethical business decisions.

The original UP had to surmount three hurdles: Project design and funding, construction, and regular operations. The railroad accomplished the first two splendidly and badly botched the third.

First, according to the political and cultural climate of the times, to be approved and funded, the Transcontinental Railroad had to be represented as an old-fashioned, patriotic, and cooperatively run “public” project.

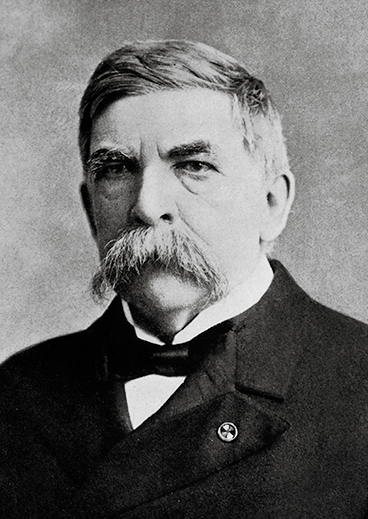

Second, in order to be built, it had to become a quasi-military organization with ruthless discipline and laser-like focus. That was the work that Gen. Grenville Dodge, the Casement brothers, and tens of thousands of immigrants, civilians, and former soldiers accomplished under harsh conditions. Too often, we understand the UP in terms of its physical construction and not in terms of its larger contexts.

Third, to operate successfully in the changing post-Civil War economic environment, UP needed to be a modern, well-managed, entrepreneurially motivated private entity with the freedom to innovate and grow. Instead, it was both constrained by the terms of the Pacific Railroad Act (authorizing what would become the Transcontinental Railroad) and hijacked by successive managements intent upon extracting whatever cash they could from an increasingly fragile and damaged company. By the end of the Civil War and the railroad’s construction, patriotic motivations had largely dissipated. The company slipped into the hands of crooks and speculators. In the “anything goes” spirit following the war, UP was structurally doomed to failure and easy pickings.

Transcontinental Railroad Challenges

It is easy to paint the so-called “Gilded Age” between roughly 1865 and 1900 as a period of explosive growth and change, unbridled greed and corruption, corporate mischief, and a survival-of-the-fittest ethos.

And, for the most part, it was.

By autumn 1863, when the UP was formally incorporated in New York, the gloss of public oversight and national purpose had begun to fade. In the year since a board of commissioners’ meeting in Chicago, the tide of war had shifted in the Union’s favor. The Transcontinental Railroad was no longer a matter of national defense.

While it may have been inevitable, it was unfortunate that UP evolved into the kind of speculative entity then common on Wall Street. Control passed to groups of manipulators and financiers who regarded the railroad as a kind of 19th-century automated teller machine. While front-line railroaders and operating managers strove to run an effective railroad, the company itself seemed constantly in play in the casino economy of the time.

The Union Pacific of the late 19th century was challenged by inept management, serial scandals, two financial panics, two bankruptcies, political pot shots, and the kinds of external events that damage even strong corporations. Mark Twain coined the era “The Great Barbeque.”

How was the transcontinental railroad funded?

Perhaps the cleverest scheme UP’s management executed was Credit Mobilier of America, the independent construction company hired to build the Union Pacific from Council Bluffs, Iowa, to Ogden, Utah. The original idea was to keep everyone honest by separating the management and operation of the railroad from its construction. That way the government could closely monitor payments, and the company could ensure that it was getting fair value for its money.

In practice, the use of supposedly separate construction companies was a splendid way to set up regular embezzlement programs. On the UP, a group of the railroad’s directors and officers owned Credit Mobilier, which meant that Credit Mobilier could (and did) submit grossly inflated invoices to the UP for payment by the U.S. government. It wasn’t explicitly illegal, and there were few consequences for those involved. The one exception was Congressman Oakes Ames, who as president of Credit Mobilier had been especially generous in providing his colleagues with cash gifts and opportunities to buy stock on favorable terms.

Politicians who got Credit Mobilier stock profited handsomely, either through dividends (sometimes 100 percent) or by selling the shares at inflated values. Naturally, the 30 or so congressional beneficiaries of Credit Mobilier’s generosity were staunch advocates of additional funding for the railroad’s construction. This particular scandal broke during the 1872 presidential election. In an unseemly case of scapegoating, Oakes Ames was censured and died soon afterward.

Even when UP tried to grow its business legitimately and confront rising competition from newly completed transcontinental railroads, it faced sustained criticism for building “branch” lines. These were secondary main tracks to places like Denver and Julesburg, Colo., and Pocatello, Idaho. Critics argued that UP was legally bound to remain a bridge line, and that the lateral lines represented a misuse of capital or a violation of its original purpose.

In fact, it was clear that traffic generated by these additional lines was keeping the railroad alive. It would be enough to help the railroad become what it is today.

Interested in learning more about the history of the Transcontinental Railroad? You’ll find it in our special issue, available online.