Caboose

For more than a century, the caboose was a fixture at the end of every freight train in America. Like the red schoolhouse and the red barn, the red caboose became an American icon. Along with its vanished cousin the steam locomotive, the caboose evokes memories of the golden age of railroading.

There are conflicting versions of how the caboose got its name and where the word was first used. One popular story points to a Dutch derivation of the word “kabuis,” meaning a little room or hut. The English word “caboose” was first used as a nautical term for a ship’s galley.

More certain is the origin of the first railroad caboose, which can be traced to the 1840s. A conductor named Nat Williams on the Auburn & Syracuse, a short line in upstate New York, decided to use the empty wooden boxcar at the end of his train as his “rolling office.” Williams sat on a wood box and used a barrel as his desk. He stored flags, lanterns, chains, and other work tools in this first caboose.

The genesis of the unique cupola located atop the caboose is credited to T. B. Watson, a Chicago & North Western conductor. In 1863, when Watson’s regular caboose was reassigned, he used a wooden boxcar at the end of the train for a caboose. The boxcar had a hole in the roof, which prompted Watson to sit on a stack of boxes with his head and shoulders protruding through the hole, giving him an excellent view of his train as it journeyed from Cedar Rapids to Clinton, Iowa. Back at the home terminal, Watson relayed his positive experience to a master mechanic at the railroad’s Clinton shops. He suggested that a “crows nest” be added to the new waycars the North Western was building there. Thus, C&NW may have been the first railroad to have cabooses with cupolas.

A train crew’s home away from home

As the crew member in charge of the train, the conductor needed space to check car waybills, wheel reports, and switch lists, and manage the train’s operation.

Before George Westinghouse invented the automatic air brake in 1869, it was the rear brakeman’s job to walk forward and turn a wheel that applied the handbrakes on each freight car, on cue from the engineer’s whistle to stop the train. The head brakeman, who rode in the engine, walked toward the rear of the train performing the same task.

After the widespread introduction of air brakes, brakemen still had the responsibility of throwing switches and coupling cars, as well as keeping an eye on the train’s consist while it was in motion.

Prior to the introduction of automatic block signals, invented by Westinghouse in 1881, it was the flagman’s job to walk a safe distance behind the stopped caboose carrying a lantern, flags, and fusees, used to signal approaching trains that his train had stopped on the main line.

In addition to the conductor’s work area, cabooses often had bunks for sleeping, stoves for cooking, and toilets (initially, the straight-dump kind, then later, chemical toilets).

The caboose was also used as a storehouse for tools and supplies, including spare coupler knuckles and pins, chains, jacks and re-railing frogs, fusees, flags, lanterns, and first-aid kits. Beginning in the 1950s, axle-driven generators that supplied lighting and electricity were added, which led to the installation of electric heaters, refrigerators, and two-way radios.

Despite its charm, the caboose’s location at the end of a train made it a dangerous place to work. The inevitable slack, incurred whenever a train started, stopped, or changed speed, rippled back to the caboose. The ensuing jolt could be so severe that it would send crew members falling to the floor, pitching into a wall, stove, or desk corner, or even tumbling from the cupola, any of which could cause serious injury.

A toppled lantern could start a fire. Derailments, picked switches, break-aparts, or emergency brake applications could also injure an unknowing crew member. A rear-end collision could be fatal to the occupants of a wooden caboose.

Crews instinctively learned to grasp the metal handrail running the length of the car near the ceiling at the slightest indication of trouble.

Safety was a shared concern among railroad employees, particularly brakemen, so much so that the first rail labor union, the Brotherhood of Railroad Trainmen, was formed inside a caboose, Delaware & Hudson Canal Co. No. 10, on Sept. 13, 1883. That caboose is on display in Oneonta, N.Y.

Caboose construction, design, and paint

Before cabooses, the rear train crew would often ride in a coach or empty boxcar at the back of the train. The earliest cabooses were, in fact, second-hand freight cars built of wood — flatcars outfitted with a crude shelter, or converted boxcars with windows, a stove, and a desk.

Some of the companies who manufactured cabooses for the railroads were the International Car Co., St. Louis Car Co., and American Car & Foundry.

At various times, the railroads themselves would also build cabooses.

By the late 1920s, newly constructed freight cars were taller than most cupolas. This prompted the invention of the bay window caboose, pioneered by the Milwaukee Road and the Baltimore & Ohio. Built with one set of windows on each side, projecting out from the side wall to form a viewing alcove, the bay window caboose allowed the conductor and brakeman to view each side of their moving train. This type of caboose was cheaper to build than the cupola, and also helped solve tunnel clearance problems faced by many eastern railroads.

The Milwaukee Road is also credited with building the “rib-side” caboose. For added strength, narrow steel ribs were welded to the car’s side panels. Between 1939 and 1951, the railroad’s Milwaukee Shops built 315 rib-side cabooses.

In large rail terminals and urban cities, transfer cabooses were often used. They were similar in design to the early wood, shanty-type caboose, and were very plain inside, with only a desk for paperwork. The large, outside storage platforms were used to haul work material, spare couplers, and tools. The transfer caboose usually did not travel far from its home terminal, and was popular with big-city belt and terminal railroads.

Railroaders affectionately called their cabooses by many nicknames, including cabin, crummy, buggy, doghouse, waycar, shack, and hack. On the Pennsylvania Railroad, the caboose was a cabin or “cabin car.” The Burlington, C&NW, and other roads used the term waycar. Canadian cabooses were called “vans,” a word similar to “brake van,” used in England to describe railroad cars that performed a similar function to a caboose.

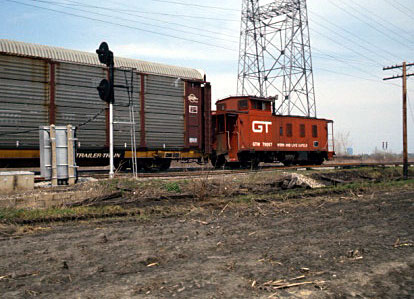

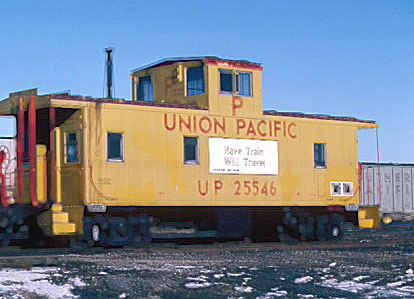

Most railroads painted their cabooses “boxcar red” for high visibility. However, after World War II, the “little red caboose” showed up in many different colors, typically associated with the paint schemes found on the railroads’ new diesel locomotives. The colorful caboose with its railroad’s logo and paint scheme presented a rolling image for everyone to see.

Denver & Rio Grande Western had cabooses of silver and gold, while Milwaukee Road’s were orange and black. Pennsylvania Railroad cabooses were painted “Tuscan Red,” and Southern Pacific’s were reddish brown. Chesapeake & Ohio liked to paint its cabooses yellow and blue, and Boston & Maine chose black and blue.

Chicago & North Western waycars were various shades of yellow and green, while Burlington Route’s all-steel waycars were painted silver. A popular color for cabooses was green, some shade of which could be found on roads such as the New York Central and successor Penn Central, Northern Pacific, Lehigh Valley, Indiana Harbor Belt, Reading, Rutland, and Missouri-Kansas-Texas.

Two latter-day caboose colors were Burlington Northern “Cascade Green” and Conrail blue.

Technology catches up

In railroad jargon, the caboose was classified as “non-revenue” equipment.

Cabooses were expensive to build and maintain, unlike regular freight cars, which earned their keep. Extra switching moves were needed to add or uncouple a caboose at the end of a train, and they required caboose tracks at major yards, as well as carmen and laborers to work on and service them.

In 1980, the cost of operating a caboose was 92 cents per mile. One terminal superintendent on the Cotton Belt estimated his railroad spent $300 a day in crew time switching out cabooses at terminals. To many railroad accountants, the caboose was “just along for the ride.”

As railroad technology advanced, the caboose’s function became less important. The introduction of remote switches thrown by dispatchers at CTC consoles meant that a rear brakeman wasn’t needed to close a switch behind a train. Increasingly taller freight cars blocked the view from the cupola.

Many railroaders believe the final nail in the caboose’s coffin was the “End-of-Train” telemetry device. This small metal box was first used by the Florida East Coast Railroad in 1969. The EOT fits over the rear coupler of the last car on the train, and is connected to the train’s air brake line. Powered by battery, the EOT sends a periodic signal to the locomotive indicating the brake pressure at the rear of the train, whether or not the last car of the train is moving, and in which direction. EOTs are also equipped with a flashing red light, activated at night by a sensor, which serves as the train’s rear marker.

By 1972, Florida East Coast had replaced all of its cabooses with EOTs, and other railroad soon began to follow suit. In 1985, Robert Claytor, then chairman of Norfolk Southern, summed up the reasons for doing so in an address to the Railroad Public Relations Association.

“Today’s caboose costs about $80,000 — more than the cost of most freight cars — and weighs about 25 tons. It can be replaced with a box that costs about $4,000 and weighs 35 pounds. The end-of-train monitor doesn’t have to be switched through terminals and doesn’t require expensive maintenance … The fact of the matter is that the caboose is certainly the most dangerous place to ride.”

By the mid 1980s new labor agreements reduced the hours of service for train crews, eliminating the need for a caboose to provide overnight housing. The labor agreements also cut crew size from five to four, and finally two — an engineer and conductor, both of whom could ride comfortably in the locomotive cab. Included in the agreements were provisions for the removal of cabooses from the rear of freight trains.

One by one throughout the 1980s, individual states repealed age-old laws that required the use of cabooses in train operation. The last state to do so was Virginia, which relented on July 1, 1988. Not long before, in December 1987, the Canadian government approved the cabooseless operation of freight trains provided a two-way EOT system was used in its place.

In the mid 1920s there were approximately 34,000 cabooses operating on U.S. railroads. Today, only a few hundred cabooses remain, used in transfer work, and on yard jobs, work trains, and trains that require backup moves.