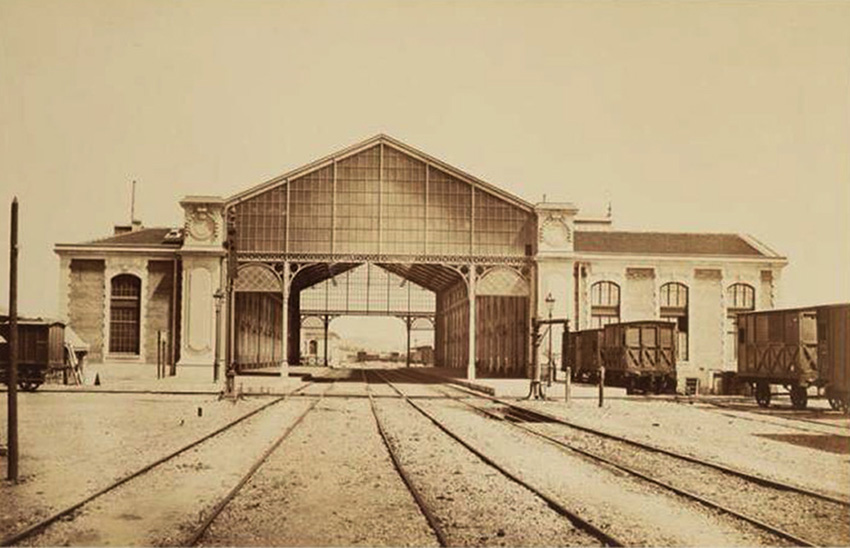

Toulon Station, c. 1861. Édouard Baldus, who trained as a painter and worked as a lithographer, adopted compositional conventions of painting, such as centered motifs and balanced space surrounding the center, to his railroad photographs.

As photographers of railroads, we are not often aware that our images owe a great deal to traditions first set by painters and not by other photographers. Conventions of composition, choice of scene, and even the qualities of light that rail photographers seek out all have roots in conventions first set in paintings.

Railroads were one of the first subjects that early photographers turned their lenses toward, and these early images were often composed using the same conventions as paintings. Ian Kennedy, curator of European painting and sculpture at the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art in Kansas City, Mo., points to the example of Édouard Baldus (1813-1889), one of the most important of these early rail photographers. Baldus’ photos were “influenced by painterly values like composition, balance [from] quite classic paintings,” Kennedy said, in part as Baldus first trained as a painter and worked as a lithographer. “Like many photographers he was influenced by painting indirectly… [through] the principles of composition.”

As the medium of photography became more established in the mid-19th century, the methods used by photographers and painters to depict railroads began to diverge. “You get the power of the locomotive [as] a subject of British and American photography,” adds Kennedy, who cites the work of famed photographer Andrew J. Russell (1829-1902). “In his [photos of] the building of the transcontinental [railroad], the locomotives are the heroes.” Scenery is secondary, stage dressing for the action undertaken by locomotive and the trains they pull.

Painters, meanwhile, largely turned away from locomotives. A fine example of this is Lackawanna Valley, an 1855 painting by George Inness (1825-1904). Inness had been hired by the Delaware, Lackawanna & Western Railroad to depict that railroad’s first roundhouse at Scranton, Pa. This structure, fully circular and topped by a dome, was both large and impressive, yet in the painting, Inness reduced the roundhouse to a tiny piece in the distance, dwarfed by the mountains behind. A locomotive and train, likewise small in size, skirt by at the bottom of a stump-strewn foreground. Landscape – in this case a denuded, exploited one – is the subject, and the railroad is but a guest or an intruder.

Convergence of painted and photographed depictions of railroads did not come about until the late 19th and early 20th centuries, with the rise of a new style. Called pictorialism, this movement sought to achieve artistic legitimacy for photography by directly adopting interpretive approaches from painting. In the U.S. its most prominent leader was Alfred Stieglitz (1864-1946) who started a photography group in New York City dedicated to advancing the new aesthetic. Among his many images, Stieglitz created two railroad photographs that remain famous examples of pictorialism, The Hand of Man (1902) and In the New York Central Railroad Yards (1903).

The images prominently depict steam locomotives billowing up clouds of white exhaust, are dramatically backlit, and are lightly shrouded by a gauzy mist that softens the whole picture. Both images are typical of the pictorialist desire to impart an interpretation of the world through the use of what Stieglitz called “atmosphere.”

Today the artistic dialog between painters and photographers is, in Kennedy’s view, “more confused.” During the 1930s, in the wake of pictorialism, photography moved towards realism, sharp focus, and a dispassionate approach to subjects. “The relationship between photographers and painters isn’t as close as it once was,” Kennedy said.

Despite this, there at least two lasting impacts that painting has had on rail photography. Consider, for example, choice of perspective and subject. Contemporary rail images that depict swaths of landscape with distant trains in full view owe a great deal to the railroad painters of the 19th century, who intentionally de-emphasized the presence of the train. Another strong example is the preference often exhibited by photographers for dramatic lighting. Rail photography made at sunrise, near twilight, or in poor weather conditions has a great deal of kinship with the pictorialist search for “atmosphere.” As rail photographers, we continue traditions nearly as old as the railroads themselves, deeply rooted in the works of other photographers, and painters as well.

Alexander B. Craghead is a member of the Center for Railroad Photography and Art, and is a writer, photographer, and creative specialist from Portland, Ore.

The Center for Railroad Photography & Art, founded in 1997, is America’s foremost organization for interpreting the intersection of railroad art and culture with America’s history and culture. It holds an annual conference at Lake Forest College in Illinois and produces numerous gallery exhibitions around the country. For more, visit www.railphoto-art.org.

FULL SCREEN

FULL SCREEN