A century can seem like a long time, especially given the accelerating rate of change that oppresses all of us. At the same time, 100 years is one long lifetime.

Almost 100,000 now-living Americans were on this Earth in 1925, the year a group of Black Pullman employees organized the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters and Maids in New York. That August, they selected a young labor activist named Asa Philip Randolph as their president.

The BSCP represented sleeping car porters and other on-train employees for only about 40 years, but it was much more than a smallish railroad labor organization. In a variety of ways, BSCP and its members played crucial roles in the modern civil rights movement. Just as largely White railroad unions pioneered progress in issues such as collective bargaining, workplace safety, the eight-hour day, and social safety nets, in the mid-20th century Randolph’s Brotherhood gave shape and substance to evolving principles of fairness and equality under law. It is just one example of how railroading helped shape America in ways we have not yet fully appreciated.

The Long Struggle

African Americans worked on the railroad from its very beginnings, as employees, slaves, and casual labor seeking a toehold in a rapidly expanding economy. Unlike Irish, German, and other European migrants, African Americans continued to be restricted to more menial and taxing jobs. They could be firemen but never engineers, track laborers but not roadmasters. In the South, that remained the pattern through much of the 20th century.

Railroad mobility was so central to American life in the 19th century that it was a railroad case before the Supreme Court — Plessy v. Ferguson in 1896 — that interpreted the 14th Amendment to mean that discrimination against minorities was legal, so long as “separate but equal” accommodations were provided. In practice, facilities might be separate, but were rarely equal. None of this is “woke” or political correctness. It is basic American history. Glossing over those realities obscures the remarkable and sustained struggle Pullman porters waged over a half-century merely to establish the right to form a union and collectively bargain with one of the most powerful (and openly racist) corporations in America. That was not an anomaly, as much of the United States embraced segregation. For many decades the restaurant in Union Station was the only fine dining establishment in Washington, D.C., serving Whites and Blacks without distinction.

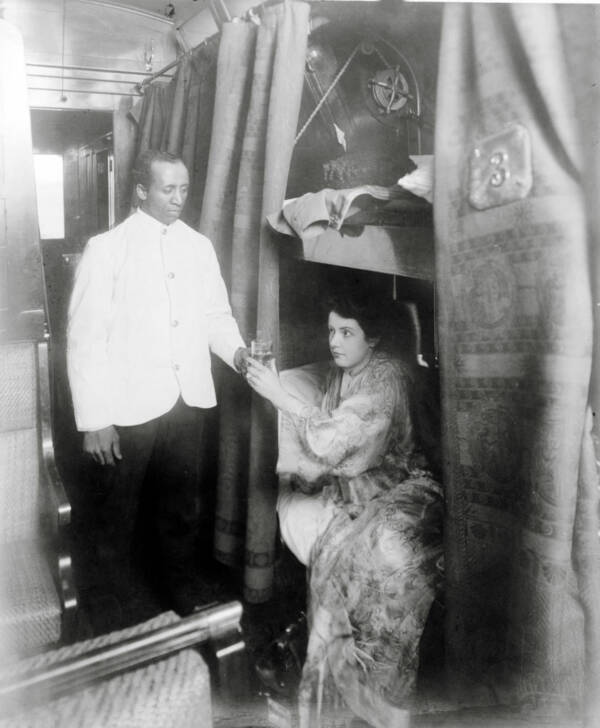

George Pullman was a classic 19th century tycoon — a visionary and ruthless businessman with a highly contingent moral compass. One of his most effective tactics after the Civil War was to tap into three pervasive realities. One was the growing Middle Class and demand for more comfortable long-distance travel. Second was exploiting the pool of available African American labor who had few employment options in either the North or South.

Third was the perception — carefully cultivated — that Blacks were predisposed to servitude, and that the traveling public would be willing to pay for the kind of Old South charm and personal attention being romanticized in late 19th-century popular culture. A ride in a Pullman Parlor or Sleeping Car was a brief sample of “the good life” the top 10% enjoyed all the time. Keep in mind that comforts like indoor plumbing, central heat, and private vehicles were luxuries beyond most people’s reach.

The Great Emancipator’s Son

There was irony in the fact that Chicago corporate attorney Robert Todd Lincoln, Abraham Lincoln’s only surviving child, became the Pullman Co.’s general counsel, then assumed the presidency of the Pullman empire upon George’s death in 1897. The son of “the Great Emancipator” was a principal architect of the business model that sought to replicate elements of unfree labor.

In the years between the Great Railroad Strike of 1877 and the Shopmen’s Strike of 1922, many non-management railroad workers created effective collective bargaining organizations and voluntary associations such as insurance and savings institutions.

All railroad work could be harsh. Employment policies were often arbitrary and capricious, and there was no social safety net of any kind. At the turn of the 20th century, an average of 10 to 12 railroaders were killed on the job every day of the year.

Over time, the work of labor unions, Congress, and public pressure dramatically improved the lot of average White railroad employees. But the Pullman Co. was not a railroad, and remained virulently anti-union. Porters and maids had a tougher row to hoe.

Asa Philip Randolph

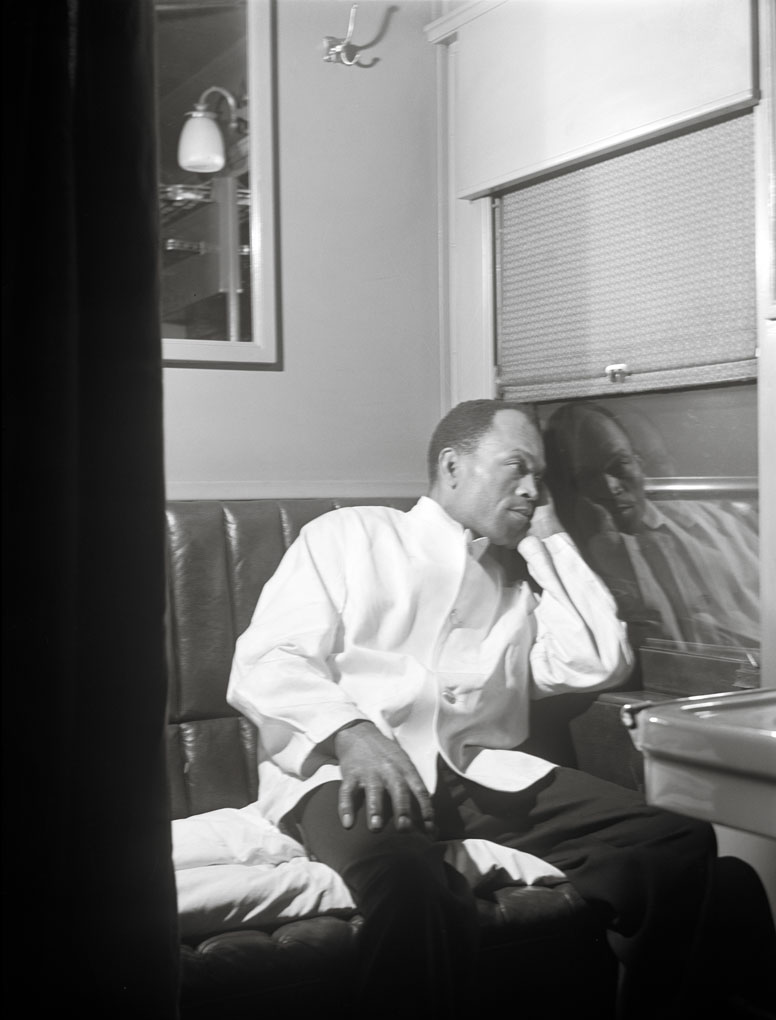

Following the First World War, change was afoot. Black soldiers who had “seen Paree” brought a new kind of activism back to the states. The Harlem Renaissance in New York, the Black Diaspora of African Americans fleeing the Jim Crow South for Northern cities, and generally shifting attitudes about race intensified the sense of exploitation felt by Black Pullman employees. Even the American Federation of Labor, the country’s largest grouping of craft unions and no one’s idea of a progressive entity, expressed more willingness to work with African American organizations.

For many years, porters and other Black Pullman employees had quietly, and sometimes surreptitiously, explored the idea of creating a union to bargain for better wages, reasonable working conditions, and some small measure of respect. The fact that the traveling public commonly referred to all porters as “George” suggests the low regard many people (and the Pullman Co. itself) had for them.

That began to change in 1925, when a group of porters gathered in New York City to create a labor organization strong enough to challenge the Pullman Co. Lincoln had retired as Pullman’s chairman three years earlier, and would be dead by 1926.

The organizing committee chose a charismatic Black labor organizer to lead the new Brotherhood. Asa Philip Randolph was educated, an eloquent speaker, and tenacious advocate. He also faced formidable opposition from the Pullman Co. The porters and maids had few allies, unlike White railroad workers seeking to form (or join) unions. The railroad industry itself was largely silent — it wasn’t their fight. Mostly Southern railroads and their largely White craft unions had already made labor agreements restricting promotion opportunities for Black employees. Even the American Federation of Labor (AFL) refused to recognize the nascent BSCP as a legitimate craft union.

The Pullman Co. deployed the customary coercive measures to stymie any union organizing activity. Porters or others known to be actively working to organize were summarily dismissed, which was perfectly legal. In turn, the porters used their mobility and national networks to quietly pursue the work of strengthening the BSCP, aided famously by their wives. In its first decade, the Brotherhood did not thrive — but it survived.

The onset of the Great Depression around 1930 made things worse for just about everyone, but paved the way for the vast program of reforms we know as “The New Deal.” Some of the ideas seemed radical, like Social Security. While relief of suffering was the initial New Deal objective, structural reforms addressing inequalities and emphasizing economic fairness followed closely, and the BSCP saw an opportunity.

The idea that workers had rights at all was still anathema to many employers. Roosevelt’s various fair labor laws, and shifting public sentiment, finally compelled the Pullman Co. in 1935 to begin collectively bargaining with BSCP regarding wages and working conditions. The issues at stake were both large — a more reasonable living wage — and smaller, such as the company paying for porter’s uniforms and reducing harassment of union activities.

By 1937, porters and maids finally achieved the kinds of rights many White railroad craft unions had won 40 years earlier. Pullman scholar David Duncan notes that the Pullman Co. had followed society in general, improving relations with all of its employees and treating porters and maids with greater respect. They had a greater presence in the company’s publication Pullman News, and even began working as porter trainers — a small, but symbolic, advancement. There is further irony in that just as the Brotherhood was coming into its own in the mid-1930s, rail passenger travel began its quarter-century secular decline in earnest. There were upticks during and after World War II, and occasional signs that Pullman travel had a stable future, but in hindsight the writing was on the wall. The demise of the Pullman Co. as a national institution was remarkably swift. By 1969, even before Amtrak was created, it ceased operations altogether.

The work of A.P. Randolph and his BSCP colleagues Milton Webster, C.L. Dellums, and a dozen more, had not been confined solely to Pullman labor issues. It was rooted in evolving notions of fairness and equality in times of great social and cultural flux. As the first major national African American labor organization, it was natural that BSCP would play a leading role in the modern Civil Rights movement. They did not think of themselves solely as railroaders so much as advocates for a better, more fair American society. That had also been true of the railroad labor leaders a half-century before.

A.P. Randolph was a young man growing up in Florida in 1896 when the Supreme Court decided the Plessy case. In 1925, the year he helped found the BSCP, Homer Plessy died in New Orleans. Randolph was still active in 1953, when the Supreme Court effectively overturned that decision, and he lived to see landmark legislation such as the 1965 Voting Rights Act that further protected Americans from insidious discrimination.

Randolph retired as president of the BSCP in 1968, after leading the organization for 43 years. In 1978, the by-now vastly smaller BSCP merged into the Brotherhood of Railway & Airline Clerks, which through the Amtrak Service Workers Council continues to represent on-board Amtrak employees. Randolph died in New York City in 1979, not long after his 90th birthday. That same year, Amtrak introduced its Superliner I bilevel cars, with George M. Pullman’s name on sleeping car No. 32009.

A version of the Pullman Co. survived until 1981, largely to resolve longstanding disputes with the BSCP. For many of us, that is well within living memory. It wasn’t until Superliner II No. 32503 rolled out of the factory 15 years later that A. Philip Randolph’s name graced the side of a sleeping car. Bombardier built the car to Pullman Co. patents at its Barre, Vt. plant — a hundred miles from Robert Todd Lincoln’s summer estate at Hilsmere, near Manchester. One last irony: Have the 32009 and the 32503 ever run coupled together in the same train? Did anyone notice? Did anyone care?