NEW YORK — Lost in the debate between Amtrak, New York Gov. Kathy Hochul, and transportation advocates over the plans to close Amtrak’s East River tunnel for repairs — and the resulting service reductions, especially for Empire Service trains to and from Albany-Rensselaer, N. Y. — are the limited track routing options that exist between Penn Station platforms and the tunnels that feed trains to them.

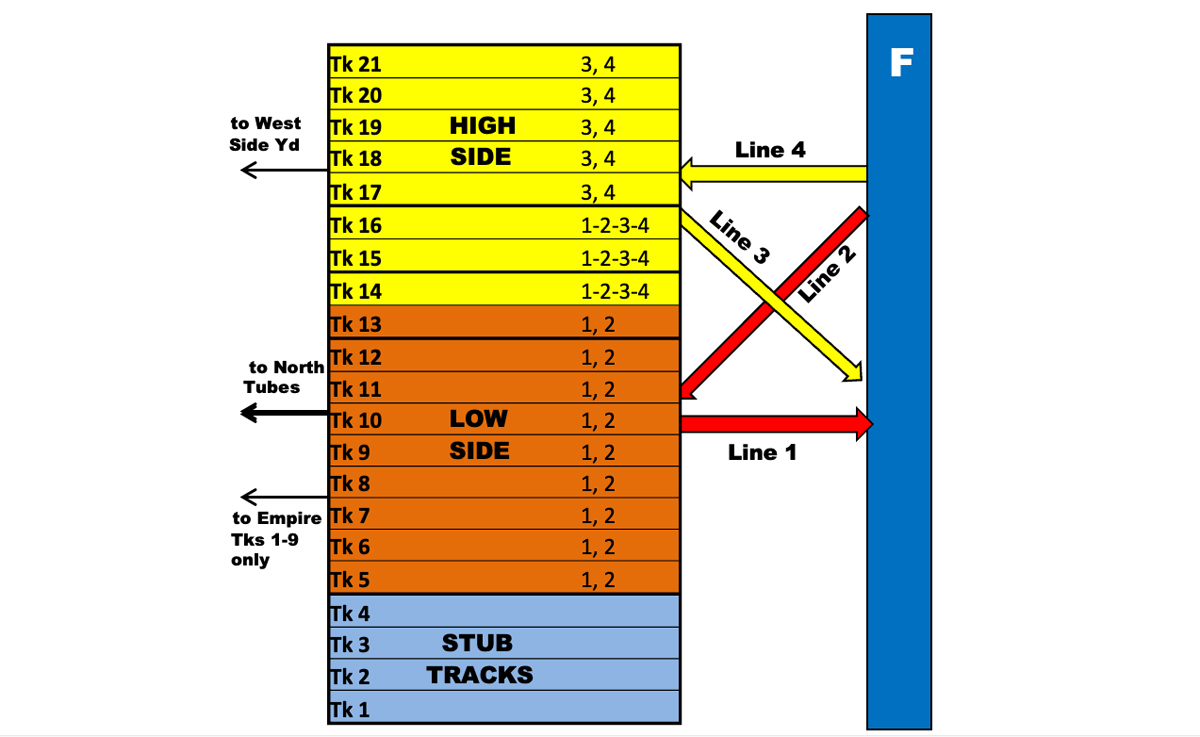

As depicted in the schematic diagram above, developed by retired Amtrak operations strategist Walter Peters, not all tracks have access to all East River tunnels. The numbers on the right side of the diagram of each of Penn Station’s 21 tracks show which tunnel that track can access via a series of ladder tracks east of the station. Deterioration caused by Hurricane Sandy’s saltwater intrusion in 2012 has prompted the company to close and rehabilitate the “Line 2” tunnel first.

On the east end

If all tubes were available to serve every track, closing Line 2 would be less of an issue. But only three tracks have such all-tube access.

Line 2 typically hosts westbound through trains from Boston or Springfield, Mass., and deadhead Amtrak and NJ Transit equipment moves from Sunnyside Yard in Queens. But Line 4, the other westbound tunnel route, can only feed trains to tracks 14 through 21. The only direct East River tunnel option for tracks 5 through 13 is Line 1, normally handling only eastbound traffic. With Line 2 closed and Line 1 handling trains for those tracks in both directions, trains must now wait for opposing traffic, which is not normally the case. The result is a reduction in the total number of trains tracks 5-13 can handle in any given hour.

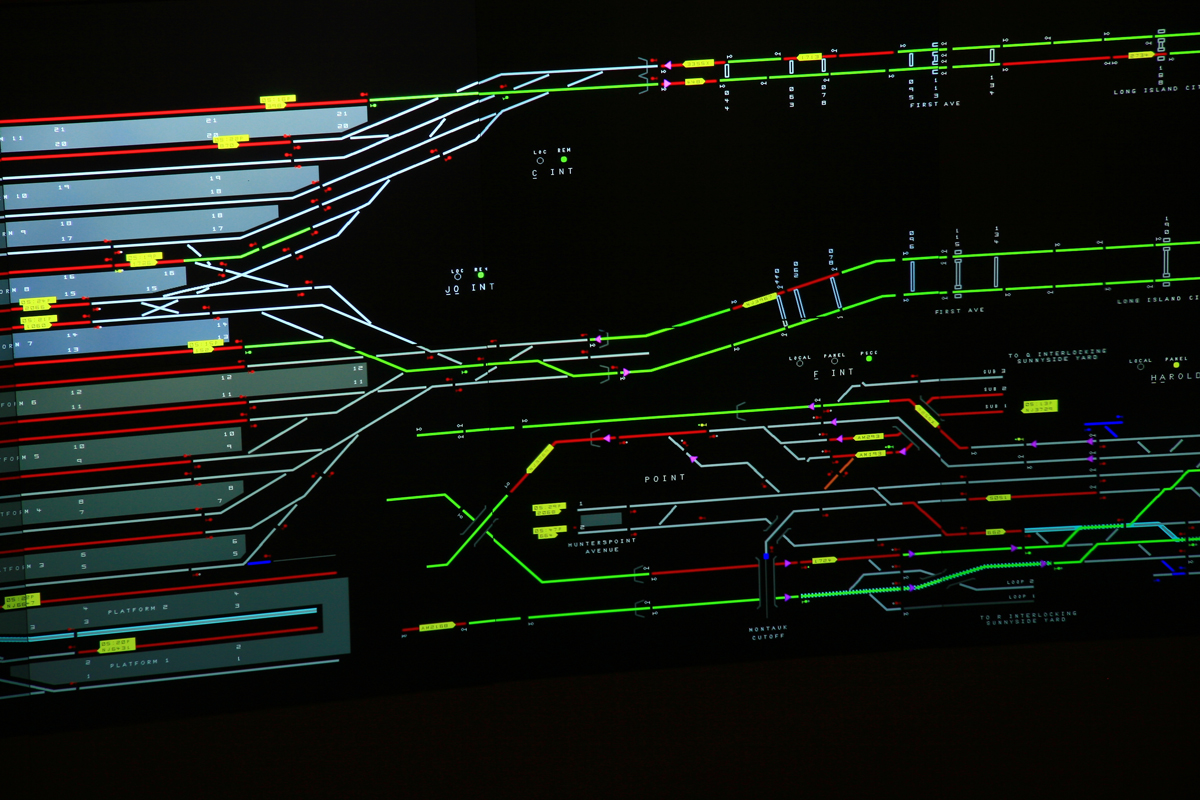

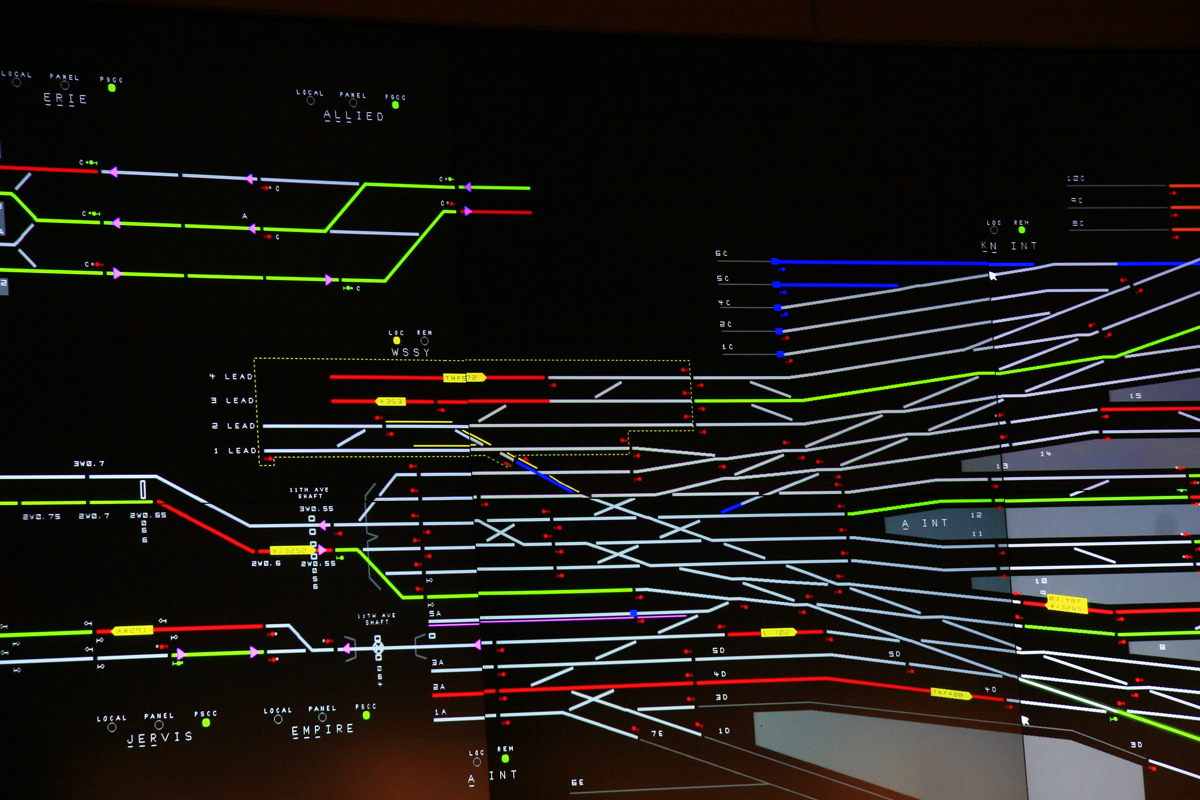

The image above, photographed in 2008 at Penn Station Central Control for a Trains feature on station operations [“Penn Station: How do they do it?,” January 2010], shows how platform and tunnel tracks are linked. The lower part of the photo also depicts how westbound Line 2 crosses eastbound Line 3, so that trains from both parts of the station wind up facing the same direction east of the river. This further complicates “wrong way” moves on Line 1 at Sunnyside and through Harold Interlocking.

Given this track plan and the fact that Long Island Railroad trains lay over between rush hours in the Hudson Yards west of the station, most LIRR trains use the high-numbered tracks.

On the west end

A compounding challenge for Empire Service trains and the Lake Shore Limited is that they enter the station south of the twin Hudson River tunnels. Limited space for ladder tracks means they can only make direct moves to tracks 1 through 9. Of these, only tracks 5 through 9 connect to the East River Tunnel Lines 1 and 2. Tracks 1 through 4 can accommodate push-pull Amtrak Keystone and NJ Transit trains able to forego servicing at Sunnyside. The push-pull Empire Service trains can also use these tracks. With Line 2 out of service for an extended period, this puts a severe track-capacity strain on Penn Station’s ability to handle a full schedule.

Trains to and from New Jersey have access to any track; the fact that Long Island’s West Side Yard equipment moves have a direct path to the higher-numbered tracks means there is seldom any interference with through Amtrak trains. Track capacity varies from eight cars (tracks 1 through 3) to 17 cars (tracks 11-12). Tracks without direct tunnel connections can be utilized, but this involves tying up ladders at either the east or west end of the station for train repositioning, further adding to congestion and delays.

Some of these details may have changed because of platform and track construction since a detailed Trains analysis was completed in 2009, but Penn Station’s basic layout has not. If no significant changes are made to expand trackage and switching options, the value of NJ Transit-Long Island Rail Road run-through trains is questionable in light of existing constraints. Such run-through operation is frequently cited by advocates as a way for Penn to handle more traffic without a major track expansion project [see “‘Through running’ concept not enough …,” Trains News Wire, Aug. 6, 2024]

With these constraints, it’s understandable why Amtrak management opted to reduce Empire Service arrivals and departures, and to convert many of those trains to push-pull operation. Still not satisfactorily explained, however, is why timings for the Montreal-bound Adirondack and eastbound Maple Leaf from Toronto couldn’t have been adjusted. Those trains are now combined between Albany-Rensselaer and Penn Station, leading to layovers exceeding 90 minutes for the northbound Adirondack and the southbound Maple Leaf. Given that the tunnel rehabilitation is slated to continue into 2027, there is still time to come up with better solutions.

This article contains incorrect information, as track 17 is also accessible from all 4 lines…kindly update your article accordingly!!!

Charles,

Thanks for your correction. As stated, there has been interlocking reconstruction that may have affected tunnel accessibility to and from various tracks.

For those looking at the track diagrams for an understanding of the issue, it helps to understand that east of 7th Avenue, East River tunnels 1 and 2 are under 32nd Street and 3 and 4 are under 33rd Street. In other words the two pairs of tunnels are one block apart, not side-by-side, and that is why there is no easy way for access to most station platforms from each tunnel.

Mr. Becker’s remind that the extensive work on the Park Avenue viaduct is going on the same time Amtrak has decided to kick off the East River Tunnels rebuild plays into this. That is invaluable information for those examining how to reduce service impacts, especially on the Empire Service. So where was the rail division at NYStateDOT to oversee the scheduling of the two major projects was so as to reduce the impacts to train service for all three carriers? And they are the guys paying for the Empire Service per Section 209 of the 2008 PRIIA.

Regarding the excessive dwell at ALB for passengers on Train 69 going to stations north of ALB, was CPKC ever asked if they would slot #69 north of Schenectady as much as an hour earlier so as to avoid that situation? Or, were they asked and they refused? Seems to me that possibly should have been on the table.

The illustrated track diagrams are beyond fascinating. And no real changes since the PRR built the Station.

How the tug of war ends up will be interesting.

Why isn’t Amtrak moving trains that travel north along the Hudson to Grand Central during this period of construction? I think they’ve done so in the past in order to relieve congestion at Penn Station?

When this happens, where are the coaches and locomotives serviced?

Couldn’t the trains deadhead north to the Hell Gate Bridge and then south to Sunnyside, or is there only access to Sunnyside from Penn Station?

Yes, Amtrak has operated to/from Grand Central during the summer of 2018, when the Spuyten Duyvil bridge was re-built, forcing the closure of the Empire Westside Line.

But Metro North is currently rehabilitating the Park Avenue viaduct, which is constraining capacity to/from Grand Central also.

In addition, the age-old issue of the New York Central-era under-running third rail vs. the Pennsylvania-era over-running third rail comes into play. Amtrak’s P32 dual-mode locomotives are set-up for the over-running third rail for Penn Station and come be switched over to under-running for Grand Central, but not on the fly. Having a mix of over-running and under-running P32’s would limit operational flexibility. And to further complicate matters, Amtrak’s P32’s are near (or past) their intended service life which causes ongoing reliability issues.

Reportedly the concept of Amtrak leasing a Metro North trainset for use solely between Grand Central & Albany is a potential option worthy of consideration.