WINNIPEG, Manitoba — The Transportation Safety Board of Canada has called for implementation of a form of positive train control on Canadian railroads and new crew training measures as a result of its investigation into a 2019 collision of two Canadian National trains near Portage la Prairie, Manitoba.

The TSB found that factors in the accident on Jan. 3, 2019, in which one train failed to react to a signal and hit the side of another train at 23 mph, included a lack of alertness on the part of the engineer because of a lack of activity related to use of the Trip Optimizer system (similar to automotive cruise control), as well as fatigue; differing levels of experience that led to conductor to defer to the engineer when he failed to react to the situation; and the lack of a train control system that could slow or stop the train when the crew did not react to a signal alerting it to stop.

“The United States has fully implemented a positive train control system on all high-hazard track required by its federal legislation. This includes the U.S. operations of both CN and Canadian Pacific, which have invested significantly in their locomotive fleets and infrastructure,” TSB Chair Kathy Fox said in a press release following a Wednesday news conference. “The railway industry must act more quickly to implement a similar form of automated or enhanced train control system on Canada’s key routes to improve rail safety and avoid future rail disasters.”

The board also recommended that Transport Canada require railroads to develop crew resource management, or CRM, training — procedures originating in the airline industry to improve safety by addressing communication and decision-making skills.

“The aviation and marine industries experienced significant safety benefits with the introduction of CRM,” Fox said. “This type of training could provide additional tools and strategies to train crews to mitigate inevitable human errors, providing significant safety benefits in the rail industry.”

Communication issues contributed to accident

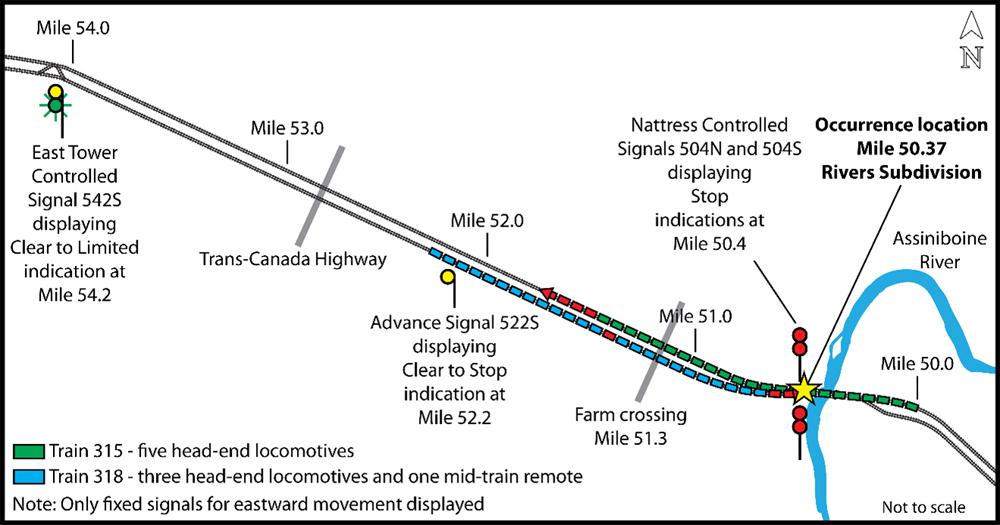

The accident occurred shortly after 6 a.m., after CN train 318, traveling east on CN’s Rivers Subdivision, passed a Clear to Stop signal indication at mile 52.2. The conductor called out the signal but the engineer did not respond and the train, with the Trip Optimizer system in use, continued at track speed. There was no further conversation.

At mile 51.13, with train 318 traveling at 46 mph, it passed the head end of westbound train 315. At this point, the conductor of train 318 reminded the engineer of the Clear to Stop indication, and the engineer disengaged Trip Optimizer and made a full service brake application; some 34 seconds later, when a Stop signal came into view, the engineer placed the train into emergency. Seeing the train would not stop in time, the two crew members jumped from the train as it collided with train 315 at Mile 50.37, where the two tracks became a single track, sustaining minor injuries. Train 318 was traveling at 23 mph at the time of the collision.

Two of train 318’s three locomotives derailed, along with eight cars of train 315, with a fuel spill of about 3,500 gallons from the derailed locomotives.

Along with fatigue issues, the TSB report asserts that, as demonstrated in this incident, “when there is a significant difference in level of experience between operating crew members, an authority gradient may develop in which the less experienced crew member may not always intervene to ensure compliance with all of the rules. … a less experienced employee may be reluctant to question the actions of a more senior employee or intervene in the operation of the train even when it may be critical to do so.” [The engineer on train 318 had hired on as a switchman/conductor in 2011 and become an engineer in July 2015; the conductor had been hired in November 2017 and qualified as a conductor in March 2018.]

This factor led to the TSB’s call for crew resource management training, which it says “seeks to improve a crew’s skills, abilities, attitudes, communication, situational awareness, problem solving, and teamwork.” The agency said it has investigated eight other incidents, dating to 1996, where ineffective CRM practices contributed to accidents. It therefore has recommended that Transport Canada require railways “to develop and implement modern initial and recurrent crew resource management training as part of qualification for railway operating employees.”