Almost exactly 160 years ago, the American Civil War wound down to a messy and anticlimactic end. By December 1864, it was apparent the Union had prevailed. It didn’t necessarily win, but at least southern secession had been thwarted.

If noticed at all, the anniversary might be an occasion to recount the many roles railroading played in the war. The standard narrative is that railroad mobility was a crucial supporting factor in supplying and enabling northern armies, ensuring victory.

I’d like to turn that well-worn interpretation on its head and ask a different question. What did the war do to, and for, railroad transportation? The changes were rapid, profound, lasting, and formed the real basis for a century of truly “modern” railroading.

The Pioneer Phase

We toss about the term “pioneer” without having to be specific. Some pioneer phases unfold over hundreds of years. Proposing 35 years (1825-1860) for railroading’s pioneer phase doesn’t seem unreasonable.

The first dozen years were on a steep learning curve. Then came the Panic of 1837, an economic upheaval second only to the Great Depression of almost a century later. It wasn’t until about 1850 that the country was humming along again and in a position to expand beyond the Mississippi Valley.

While the 1850s were productive and railroading did innovate (the initial adoption of steel, embrace of the telegraph, use of coal as fuel, opening of reasonably long railroads), it generally remained conservative (almost timid) in its business models and strategic thinking. That was especially true in the South.

Northern railroads recognized the need to connect major cities, connect seaports with productive hinterlands, and generally understood that railroad mobility, mixed economic development, and prosperity were intertwined and mutually reinforcing.

In the South, coastal and riverine transport linked major places. Railroads primarily connected major coastal cities with interior points catering to the cotton trade, the foundation of the economy, the plantation system, and foreign trade. All three depended on slave labor.

Political power, especially in the U.S. Senate, was almost equally divided and had for decades been in a stalemate over the expansion of slavery into newly forming western states.

Three colossal forces collided to upset that delicate balance. The first was the almost irresistible pressure to expand white settlement west of the Mississippi and Missouri rivers. That was the powder.

Throughout the 1850s, railroad technology improved and capital flowed. Entrepreneurs were pushing railroads westward, opening up vast expanses of land for agriculture. The discovery of gold and silver in Colorado fed the illusion that untold wealth lay about for the taking. Railroads could provide access. That was the fuse.

The organization of territories and new states was the spark. Earlier compromises to keep the number of free and slave states equal had held for a few decades. This time, it looked like the admission of more new free states than slave states, coupled with the rise of an avowedly anti-slavery party headed by a young Illinois lawyer named Lincoln, would mean the end of chattel slavery in the United States. Lincoln’s election in 1860 made war inevitable.

Thirty-five years into the industry’s existence, railroads strongly influenced the timing, proximate causes, and even the war’s conduct. It was not unexpected. But no one was prepared for how it unfolded.

A decade of hell

Both North and South recognized, at least superficially, the potential of railroad mobility. That was demonstrated at the first Battle of Bull Run when the timely arrival of fresh Confederate troops enabled the rout of poorly organized Federals. The South was the first to move a large body of men and equipment a great distance by rail, in a surprisingly short time.

What the North quickly grasped, and the South never fully seemed to, was that conflict at this scale was a war of attrition and logistics. The Union encouraged industrial production, exploited resources, and ratcheted up every technology and advantage at its disposal. The South, for a variety of ideological reasons, avoided interfering with private industry, did not exercise much control of its railroads until it was too late, and never grasped the reality that total war required a very different way of playing the cards in your hand.

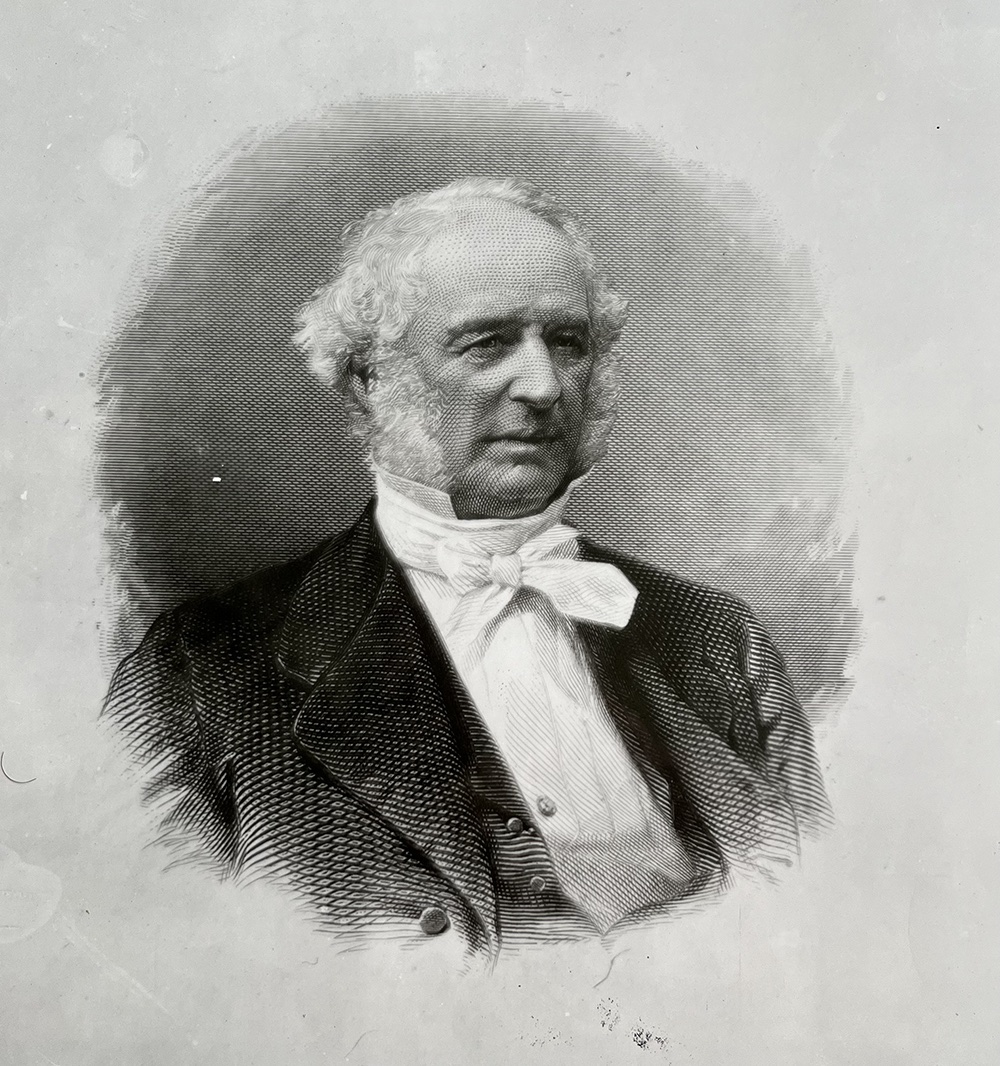

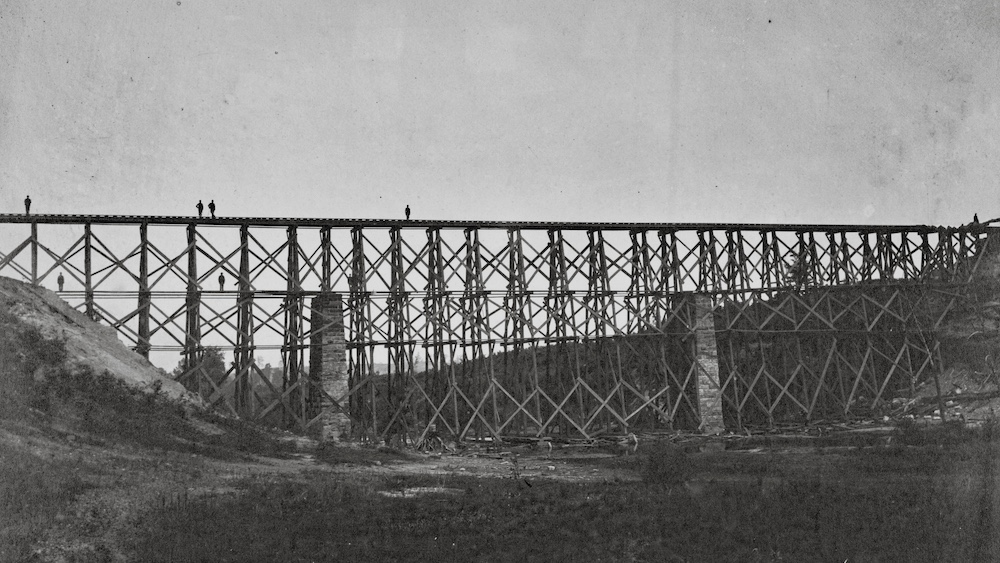

The creation of the United States Military Railroad was a stroke of genius. Its leader, Daniel McCallum, was a civil engineer by training and a brilliant organizer. He was assisted by Herman Haupt, a Pennsylvania Railroad civil engineer especially effective in the field. At war’s end, the USMRR’s scale, scope, and complexity equaled that of a Class I railroad in the 1920s. Its methods and successes were not lost on the rest of the industry.

Perhaps the most noteworthy single artifact of the Civil War was the Transcontinental Railroad, conceived much earlier but only possible after the South seceded. Construction took off with the infusion of men and resources following war’s end. Overall, it was the integration of so many systems, assets, talents, and missions that distinguishes the North’s railroad’s remarkable performance over the course of the war. It was an unrelenting trial for all involved. At the same time, it radically changed expectations as to what a railroad should, and could, be.

The Aftermath

The nation continued to reel after the trauma of the war and the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. The immediate tasks for northern railroads were to address new commercial realities, repair and replace worn equipment, and generally create a different normal after years of extreme distortion. For southern railroads, it was a matter of mere survival and trying to envision any stable future at all.

One consequence of the war is often mentioned, but rarely examined in depth. Almost overnight, hundreds of thousands of soldiers and sailors returned to civilian life in a country altered in almost every respect. Many of those veterans became railroaders because that was where the work was, but also because railroad work offered new challenges. Many had been farm boys or laborers. After seeing combat (or even in supporting roles), I can imagine it would have been difficult to return to subsistence agriculture or the vagaries of casual work.

These war-hardened men fundamentally changed the way railroading was imagined and executed. Almost every veteran brought military training and discipline, perhaps useful skill sets, and experience with rules-based operations to an industry that just a decade before had been struggling to instill those very qualities in its new hires.

What also changed following the war was a series of unprecedented convergences. To take advantage of these unfolding opportunities required the kinds of mobility only railroading could provide. Unlike the cautious, tentative Antebellum railroad industry, its postwar expression was confident, muscular, and mission-oriented.

The 1870s and 1880s comprised a bewildering wave of new science, technology, and social change. There were conflicts — the Panic of 1873 was precipitated in part by railroad financing irregularities, and the railroad strikes of 1877 and 1894 exposed deep divides in the social order. This was an age of laissez-faire economics, great wealth inequality, and levels of corruption and malfeasance that dazzled the world with its creativity and boldness.

Many tragedies and scandals — the Ashtabula train wreck of 1876 or the Union Pacific’s Credit Mobilier financing scheme (a billion-dollar scam) — prompted massive reforms in the early 20th century. Nevertheless, railroading prospered, matured into its final form, and by 1900 had solidified its role as the continent’s life-giving circulatory system.

Speculation is always risky. It is also a fine way to test our understandings of the past, and how we got here today. Anniversaries are an invitation to be skeptical and perhaps even contrarian.

Revisiting Civil War railroading is merely one opportunity. There are many more, if we have the wisdom to question established history. The past may look very different.

Read more from historian John Hankey here.