Greatest Moments

Greatest Moments Note: This speech was written by Andy Sperandeo and presented to the South Texas Division/San Antonio Model Railroad Association NMRA’s convention on June 23, 2006. We discovered these documents during some office clean up recently, and thought our readers would enjoy reading them.

Good evening everyone. I’m very glad to be with you this evening, and I appreciate your warm welcome. I still think of myself as a son of Louisiana, of New Orleans, even though I haven’t

lived there for some time. Home is an emotional more than a physical place, after all, so time is much less important than feeling in determining where it is. And when I think in those terms, I feel very much at home here with you tonight. I do claim Texas as my second home state and to a very large extent that’s because of you, my friends in the Lone Star Region.

My subject for tonight is “Greatest Moments in Model Railroading.” This won’t be about how Al Kalmbach invented the flanged wheel, or even how Keith and Dale Edwards invented the Kadee coupler. It’s going to be a more personal view.

My good friend David Barrow, when he’s impressed by the passage of a train through a realistic or especially dramatic scene, likes to proclaim that it’s “one of the greatest sights in model railroading.” I want to share some memorable experiences I’ve had in this hobby that fascinates so many of us. I hope that in doing so, you’ll be prompted to reflect on some of your own memories. I’m sure that you’ve had just as many of your own “greatest moments.”

Moment #1: Frank Ellison’s book

I remember how as a young teenager discovering the opportunities of this hobby, I found a slim book called Frank Ellison on Model Railroading, written by the man himself. Ellison, of course, was a pioneer of many aspects of this hobby, including writing about it. I didn’t really understand that at the time, but I was quite impressed by his book. I was especially captivated by his descriptions of operating sessions on his O scale railroad, the Delta Lines. It seemed to me that this must be what the hobby was all about – you built the trains, layout, the scenery and structures all to support this glorious game of running the trains as if they were really carrying freight and passengers.

Having that concept implanted in my mind so early has shaped how I’ve thought about and practiced model railroading ever since. It came as a bit of a rude shock when, as I began to meet more of my fellow hobbyists, I realized that this wasn’t a universal view. But that didn’t shake my confidence, and in fact my view of operation being the point of it all was very shortly reinforced.

Moment #2: Marc Pergament

Through a friend at Hub Hobby Shop in New Orleans, I met a man named Marc Pergament. I was invited to see his HO layout, and he suggested that my friend and I plan on staying for a while when we came so that we could watch an operating session. That was just what I wanted to hear, and the visit was everything I expected.

Marc Pergament’s HO railroad, called the Downe Yondah & New Orleans [Read Andy’s editorial to learn more about Marc Pergament: https://www.trains.com/mrr/magazine/archive-access/model-railroader-july-2001/] , was built in the above-ground basement of an old raised cottage. It was almost completely finished, with scenery, structures, trains, and controls all ready to go. Marc and his wife Jackie had built it together – with a little help from Frank Ellison, as it turned out – and they operated it together as well. Trains ran on a schedule timed against a fast clock, and way freights, streamliners, and through freights performed beautifully as they wound their way around the layout. When I think back now on what it took to have smooth running engines and rolling stock at the end of the 1950s, the DY&NO seems even more impressive.

The Pergament generously invited us back, and at future sessions we got to run trains. Four people could operate at once, two in the yards and two on the road. Everything Ellison had described was happening and I was participating in it. This was the goal of model railroading, all right, and I was more convinced than ever.

Moment #3: 1960 Lone Star Region Convention

Around the same time I had joined the Crescent City Model Railroad Club, which in those days had a layout in a garage at the home of Lou Schultz. Lou has been a great friend ever since. The club layout, which we called the Crescent Lines in imitation of Ellison’s Delta Lines, was crude and unfinished compared to the DY&NO, but we were able to operate it, and it gave me the chance to learn about how to make a model railroad work. And just as importantly, it was with a group from the club, including Lou, that I came to my first Lone Star Region (LSR) convention.

If I’ve got the history straight I think that was the 1960 convention in Fort Worth. I know we drove all night from New Orleans and planned to be at Dallas Union Terminal early in the morning to see no. 7, the 0-6-0 steam switcher we believed was still at work there. We were disappointed in that expectation, as diesel no. 8 had taken over the station chores and no. 7 would soon retire to Fair Park, but the convention was all that we were hoping for and more.

This group has always put on a good show, and we took in films, clinics, layout tours, a banquet like this one where everyone got together, and a lively auction. Of course we met lots of wonderful people, who were most hospitable to a bunch of wide-eyed Louisiana kids. They made us feel glad to be part of the LSR, as I still do tonight. We left Fort Worth excited and inspired, and talked all the way home about what we had seen and learned and how we’d put all this new knowledge into practice.

Particularly important to me was a demonstration I’d seen on how to scratchbuild turnouts, or track switches. The presenter was a 14-year-old boy whose name I’ve unfortunately forgotten, but who I recall was a protege of Jim Baugh’s from Waco.

I went home and spent the next cash I got my hands on for a soldering gun, and began building my own turnouts as fast as I could. Store-bought turnouts cost money, and that was always a limitation on my layout planning endeavors. By building my own at relatively little expense, I was freed from that restriction. That kid I’d seen in Fort Worth was only 14. I was 16 at the time, and sure I could master anything such a youngster could do.

I’m still handlaying turnouts and track on the layout I’m building today. I find that my turnouts work better than any I can buy, and I get so much enjoyment and relaxation from the craft of building them. Like all of these greatest moments, that one has turned into a lasting benefit. If you remember who gave that clinic back then, I’d be grateful to know the name. Better yet, if it was you and you’re here tonight, I’d like to shake your hand and thank you face to face.

Moment #4: Meeting John Allen

Now I’ll skip ahead a few years to what became a long string of greatest moments, my association with the famous John Allen. Like so many of us I’d been enthralled by the photographs John published of his HO scale Gorre & Daphetid RR. If you remember the impression he created in the 1950s and 1960s, you know that for that time John’s work represented the highest aspirations of model railroaders. I first got to see John in person at an LSR convention, because he had friends in the region who later would become my friends too. I recall that he gave a talk about the future of layout design and introduced the idea of building layouts with one scenic level stacked on top of another. It would be, he said, a way of fitting more railroad into our always limited layout rooms.

At that time none of my friends or I had ever seen a model railroad like that. This was before Model Railroader published the Great North Road of Francis L. Jacques, or any of John Armstrong’s ground-breaking multilevel track plans. We had a hard time imagining what John Allen had been talking about, but of course that was only one example of how far his imagination was ahead of ours.

I probably said hello to the great man at that convention, as one of the many fans he had everywhere, but I got to meet him personally and his basement empire for the first time in the winter of 1969. I was staying with friends in Redwood City, south of San Francisco on the peninsula, and I wrote to John in advance, asking if I could pay him a visit. He received requests like that all the time and was very generous with his time, perhaps not surprisingly since he lived alone and enjoyed having company. He replied with a welcome, and directions to his home in Monterey.

When I showed up on a sunny January afternoon, John greeted me and led me down to his basement. People sometimes ask me if the Gorre & Daphetid was as spectacular in person as it appeared in John’s photography. Yes, it most definitely was. Whether you took in a broad panorama or focused on a single scene, it always filled the eye and rewarded careful observation. Like the great work of art that it was, it created a world of its own and drew you in.

I was so much in awe of what I was seeing that conversation was difficult at first. I quickly learned that the best tactic was just to ask John a question about something on the railroad. He was glad to explain what he’d done and especially why he’d done it, and the more he explained the more I wanted to know.

One example I can recall was when I spotted a variety of wheelsets lined up on one of the whisker tracks at the Great Divide roundhouse. John had been part of the test program for the NMRA’s wheel contour improvements that resulted in the RP-25 recommended practice, and those were some of the different wheels that had been tried. He told me about each one of them: its design, its advantages and disadvantages, and how it performed on his trackwork. It turned out that the design finally adopted as the RP-25 wasn’t his favorite. It was pretty good, he thought, but he preferred a contour developed by George Hook of Central Valley, and called the CV-3.

Especially intriguing to me were the signs that the G D Line, as John liked to call it, was an operating railroad. There were schedules at the control panels, along with tonnage tables for the locomotives and color-coded blocking instructions for the freight trains. The freight cars carried color-coded tabs to direct their movements, and the fast clock in the station tower at Great Divide was visible from every part of the room.

When you look at pictures of the Gorre & Daphetid you might get the impression that it was built primarily for show, as a beautiful display layout. In person and listening to John talk about it, it was clear that he conceived of it as a working railroad with a definite purpose. Every track had its use and everywhere the railroad went it served some sort of industry or natural resource. The dramatic mountains were wonderful to see, but it took steep grades to cross them. As wonderful as it was to understand that John’s G-D Line was indeed built for operation, that realization led me to conclude that I couldn’t say I’d really seen it until I’d seen it at work. But I was there only for a brief afternoon, and I doubted that I’d ever get that chance.

But I did. I’d been in ROTC in college and l owed the Army a couple of years active service. That had been deferred while I finished my master’s degree, but in April of 1970 it was time to report. During training at Fort Knox, Kentucky, I filled out a preference form to indicate where I’d like to be posted after graduation. We jokingly called it a “wish list,” and none of us in our class expected to go where we chose. There was a war going on, after all.

So on the principle of “why not,” I listed Fort Ord, California, as my first choice, because it was just a short way up the road from where John Allen lived in Monterey. Amazingly enough, that’s where the Army sent me. It meant that an officer trained to lead tank and armored cavalry units was assigned to an infantry training brigade, but for the Army that was normal procedure.

As soon as I’d settled into a bit of a routine at Fort Ord, I called John on the phone, reintroduced myself, and asked if I could come to an operating session. He said he remembered my previous visit, but he tried to be discouraging about seeing the layout operate. The operators were supposed to be focusing on the railroad, he explained, and he didn’t like visitors distracting them. He also said that his sessions could be pretty intense, and might not be very interesting except for people who really liked operation. Of course, that was exactly what I was looking for, and I persuaded him that I’d watch quietly from the sidelines and stay out of everyone’s way. Which I did, both on the first Tuesday night I attended and at the next two weekly sessions. Finally, think he understood that he wasn’t going to be rid of me very easily, and invited me to take part.

John had just installed a new auxiliary control panel at the busy terminal of Port, so he could use a second engine to help with the heavy traffic. Port was meant to be a bustling industrial area with its own assigned switch engine, but with the main line incomplete, beyond that point it had to serve as a terminal as well. Mainline through freights, the Garre peddler freight, the Andrews peddler freight, and the interchange connection with Jim Findley’s Tioga Pass RR all used Port as one end of their runs. Add to that the restriction that freight cars could only be switched off and on the car ferry Annabel during the short time it was scheduled to be docked, as well as the passenger and mail trains passing through, and Port usually had more work than one engine could handle.

So I broke in on the G-D Line running the second Port switch engine, while John ran the first job from the main Port panel so he could see how the new system worked. My engine did most of the classification sorting, which gave me the chance to learn the car routing system and get a feel for where the traffic was flowing. The first engine switched most of the industrial tracks and the car ferry leads. I managed to learn fast enough not to get too far behind that first Tuesday night, and the next week I thought I was doing better.

However, the assigned engine for my job was one of the old Varney Dockside tank engines from the original Gorre & Daphetid. The little Dockside looked right at home in the waterfront setting, but it could move only short strings of cars. It couldn’t get anywhere with the longer cuts it took to build the heavy through freights, so I had to switch out a few cars at a time and shove them a long way into their assigned tracks before adding more cars on top of them.

John could see that I was taking longer than he thought should be necessary, so on my third or fourth night of running he announced that he and I would switch jobs. I got to run the first switcher and learn about the industrial tracks, and John took over the second switcher to see if he couldn’t keep up with the classification work better than I had. He quickly saw the limitations of the little tank engine, but he wasn’t going to let that frustrate his quest for efficiency. When the Dockside’s wheels started to slip, John just reached out a finger and applied a little more downforce for traction and otherwise helped it along. None of the other operators said anything about this unorthodox helping hand, so I assumed it must be the way things were done in these parts.

The next week John and I exchanged jobs again, and I was back to doing the classification work with the Dockside. I’d learned John’s secret, though, so now I took bigger bites off the incoming trains for sorting, and when the engine spun its wheels I applied a judicious finger just as I’d seen John do himself. No one said anything about me doing it either, but John saw what was going on.

Came another Tuesday night, and the G-D Line crew was assembled in John’s living room before descending the stairs for the evening’s railroading. The conversation on those occasions could be about anything, and in fact was rarely about railroading real or model. But once in a while John had something to say to us before the session began, and this was one of those times.

He’d noticed, he told us, that some people were trying to move more cars with some of his smaller locomotives than the engines could handle, and that these offenders had been putting fingers on the locomotive to either press down on the drivers or to push them along. This wasn’t realistic operation, he warned us, and explained that working within the limitations of the motive power was part of the challenge of railroading on the G-D Line. And anyway, he didn’t want our fingerprints on his weathering jobs, and all this pressing and prodding would cease as of that moment. I certainly got the message, and was only glad that no names had been mentioned, or that I wasn’t invited out the door. I made my way downstairs quietly, determined not incur more of our host’s displeasure. Once more I was designated to run the second switcher at Port, but now there was a different engine assigned to that job. In place of the little four-wheeled Dockside was one of the railroad’s sturdy PPM-United Class B Shays. It was slow but it was a real tonnage hog, and could pull or push any cut of cars the G-D could get to Port.

Sometimes I’ve heard other G-D operators talk about John’s temper, and there’s no doubt he knew how he wanted the railroad to run and didn’t mind letting us know about it. But I never felt offended by any of that, and I appreciated how he could be quietly generous to a newcomer who’d picked up one of his own bad habits. I was glad to be included in the game, and I was always willing to play it by John’s rules.

Moment #5: Meeting Pat Student

My model railroading opportunities were pretty limited at first, but eventually I found a club to join, the old Austin Model Railroad Association, and found a good friend in Pat Student. Pat was a post-doc student in UT’s chemistry department. The Austin club had a simple layout that was never intended to operate in the mode of the Delta Lines or the Gorre & Daphetid. I drew up a track plan for a new operation-oriented layout in the same space, and somehow the club agreed to tear down the old oval and build the new one.

Pat was my ally in this movement. He’s a builder and never happier than when he’s sawing wood and driving screws. We were making progress on that railroad, but as it took shape the other members seemed to loose interest. They spent their meeting nights in the adjacent club room, drinking beer and swapping stories. I had nothing against that, you know, but Pat and I had a railroad to build. One work night when the sawdust was flying, a guy named David Barrow came around with his son Thomas to see what we were up to. I suppose we greeted them politely, but we were busy and intent on our great project. After a while they left, but they did invite us to come see their layout.

Pat took David up on his invitation before I did, and he called me afterward full of enthusiasm. This David guy was for real, Pat said, and would be glad to have us help him build and operate his railroad. I went with Pat on his next visit to David’s, and that, rather than that night at the club, was the beginning of a great friendship. David had been to see the Gorre & Daphetid, and he not only knew about Frank Ellison but had actually visited the Delta Lines, an opportunity I’d never had despite living in the same city. David even liked the Santa Fe, but then who doesn’t.

There was just one little, minor obstacle to the program. David had started building benchwork in the layout room above his car port, and Pat and I could see that it wasn’t quite right for the layout we were sure David had in mind. I drew more track plans, and after hashing them out with David and Pat, he agreed to dismantle his existing benchwork and start fresh. Which we did, and the result was David’s Cat Mountain & Santa Fe no. 1 [Read more: https://www.trains.com/mrr/magazine/archive-access/model-railroader-august-2009/].

When Pat and I began spending our free time on David’s railroad, we pretty much abandoned the club. Somehow I don’t think they minded too much. They must have seen Pat and I as some kind of temporary plague, destructive enough while we were there, but at least not permanent. Not that I didn’t feel somewhat sheepish about it myself. We’d tom up one layout and moved on, and then we got to David’s and seemed to repeat the performance. I was to learn, though, that David would outdo us all when it came to changing his model railroad to try new ideas.

Moment #6: Seeing Allan McClellend’s Virginian & Ohio

We’d had Cat Mountain & Santa Fe no. 1 operating for a while when the 1975 NMRA national came along. I used to spend the summers with my mother in New Orleans while I was at UT, but I went to the convention in Dayton with Lou Schultz and some other friends from there, and met David in Ohio. There were many fine layouts on show at that convention, but we were mainly there to see Allen McClelland’s Virginian & Ohio. The V&O was famous then from its appearances in Railroad Model Craftsman – I can’t help but point out that it had been published in Model Railroader first – and we were eager to see it and meet its builder.

We did, and years later I’ve had the chance to get to know Allen a lot better. Hanging on the wall of my office at MR is a picture of me dispatching the V&O from Allen’s GRS-style CTC panel. But that’s another story.

Watch a video of the Virginian & Ohio

We were all impressed by the V&O, but none of us more than David. He didn’t rush home to model an Appalachian coal railroad instead of the Santa F7. He had absorbed the ideas of linear walkaround design with staging, and command control. He didn’t think he could quite get to where he wanted in his existing train room, however.

Although the building was 24 feet square, the useful railroad area was restricted by a sloping roof to about 18 x 24 feet. Even to get a layout that size we had accepted the limitation of keeping the side where the roof angled down lower than we would have liked.

One day soon after the convention David called me in New Orleans. “What do you think,” he asked me, “about sawing the roof off the train room and raising it to the horizontal? That would give us the full 24-foot-square room to build in.”

“David, you’re the architect,” I replied. “I’m just a grad student in American Literature. If you think it can be done, I’ll be back in the fall to help with the new railroad.”

And I was, to see David’s train room with the roof sawed free and being raised by the greatest collection of mismatched jacking equipment I’d ever encountered. The gaps above the walls were protected by plastic tarps, and already being filled in by carpenters.

In the new train room we went on to build a CM&SF that had grown from the lessons of the V&O, and that operated with the pioneering Alphatronics command control system. I say “pioneering” with some irony, as in retrospect we’d have preferred not to be quite so far out on the bleeding edge of model railroad technology. But we managed to make it work, and had some great operating sessions. They were the first of many to come on several later iterations of the CM&SF. Those of you who operated with us on Thursday night have probably seen the last of that version of the Cat Mountain Line’s Lubbock Industrial District. Having gotten to know him so well, I no longer feel the least bit guilty about what happened to that first benchwork in David’s train room.

Moment #7: Meeting Cliff Robinson

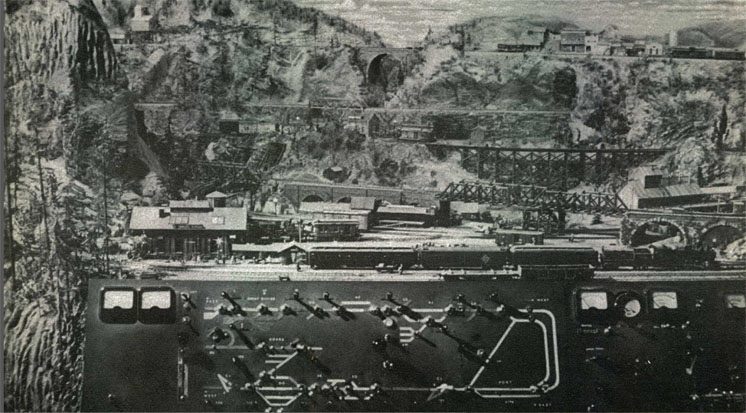

I’m going to close with a couple of Cliff Robinson stories. Cliff was one of the guiding sprits of the LSR, of course, right from its beginnings. He was kind and gregarious and had many friends in model railroading both here and across the country. I’ve operated with Cliff on the Allen McClelland’s V&O and Richard Kamm’s Sue Line in Shreveport, and Cliff was a great friend of John Allen’s too. And the first story I’ll tell you involves my buddy Pat Student as well.

Pat and I had never been to an operating session on Cliff’s Marquette Union Terminal (MUT). At the time I knew who he was – you couldn’t miss him if you belonged to the LSR – but he didn’t know me. The weekend of the OU football game in Dallas was coming up, and Pat proposed that we go to the game and then go to Cliff’s for the regular Saturday night session on the MUT.

Well, Texas lost the game, as so often happened against OU in those days, and we went on to Cliff’s house on Mockingbird Lane. As we pulled up I recognized Bill McClannahan and Jim Findley walking up Cliff’s driveway. I only knew Bill by sight, but I remembered Jim from my days of operating the G-D Line. This would be great, I thought. Then Pat and I walked in, and our reception from Cliff was pretty frosty. It turns out that Pat had found out where Cliff lived and about what time his sessions started, but he hadn’t actually talked to our host for the evening. Inviting yourself unannounced to the MUT Lines wasn’t something Cliff viewed with kindness, although to his credit he didn’t just kick us out.

While I was nervously trying to mingle with the group, which also included Jack Leming, Pete Peterson, and Mark Eskew, I noticed Cliff and Jim Findley with their heads together off to one side. Jim, good man that he was, was sticking up for me, it seemed. When Jim told Cliff he’d known me from the G&D operating group, Cliff recalled some tapes he’d exchanged with John.

In those pre-Internet, expensive-long-distance times Cliff corresponded with model railroad operators around the country by exchanging audio tapes. On one of those tapes John had told Cliff about installing the second panel at Port, and finding this young lieutenant from Fort Ord to help with the terminal switching. Whatever John told Cliff about my operating prowess, or lack thereof, it became clear to Cliff that I’d been a friend of John’s. That automatically made me a friend of his, and the nature of my welcome at the MUT Lines was dramatically improved.

Cliff was a great friend to have, and I’m proud to have known him. When I applied for a staff position at MR, Cliff wrote me a letter of recommendation. He told me he wasn’t sure it would do me much good, but I got the job.

I’d been at the magazine for a couple of years before my other Cliff Robinson story took place. Cliff had a great sense of humor, and he was especially fond of the needling kind of joke. He could slip it into you with such grace that you not only felt no pain but thanked him for it afterwards.

I was invited to a regional convention at Grand Rapids, Mich., home of Bruce Chubb and his Sunset Valley Road. Bruce is another wonderful guy I’ve been privileged to know and to work with on many of his magazine publications. Although this is a Cliff story, Bruce figures in it too.

At this time, Bruce had just converted the Sunset Valley (SV) to command control, using the CTC-16 system featured in MR articles by Keith Gutierrez [See the start of that series in the June 1997 issue.]. Bruce invited many of his friends to a special pre-convention operating session on the newly command-controlled SV. Besides myself and MR’s Dick Christianson and Jim Kelly, the out-of-region invitees included Cliff and David. Also on hand were Keith Gutierrez and his partner in developing the CTC-16, Richard Kamm. It was an all-star gathering, and since I was still relatively new at the magazine, I felt proud to be included.

Keith and Richard may have been invited as insurance against electronic problems, and whether or not that was Bruce’s intention, their services were needed. On the morning after the operating session, with convention tours to begin that afternoon, some component or other decided it was time to release the smoke packed inside it at the factory. The electronically abled among you will know that once that smoke comes out, the magic is pretty much over. Dick Christianson had the presence of mind to snap a terrific photo of, shall we say, the marker-light ends of the two visiting experts as they effected repairs under Bruce’s layout.

Everything was running again in time for the conventioneers, and Bruce’s wife Janet was even able to remind him to put on his trademark red shirt before the company showed up. I guess I’d done a decent job dispatching the layout from the SV’s CTC panel during the operating session, because Bruce asked me to help keep things moving from there while the other guest operators ran trains for the tour groups.

I did promise you that this was a Cliff story, right? As I was seated at the panel trying to keep the trains apart and clear the signals to let them run, Cliff came back to the dispatcher’s office and watched over my shoulder. After waiting politely for a lull in the action, Cliff had a question. “Andy, what are those blue lines for?” he inquired.

Bruce’s layout at that time had main lines that crossed over themselves, and he had represented that on the panel with blue lines intersecting the normal white bands of the track schematic. I explained to Cliff that that blue line on the left end of the display was really that white line on the right, and that this other blue line on the right was really the far end of this white line on the left.

“Well,” Cliff replied, “if you don’t want to tell me, you don’t have to.” And he turned and walked away.

There will never be another one like him, and the same is true of all the other friends I’ve mentioned in these tales you’ve heard so patiently. I likely wouldn’t have known any of them if we weren’t all so involved in this wonderful hobby. It’s been my pleasure to share some of my greatest moments of model railroading, and I hope I’ve reminded you of some of yours.

Thank you very much.

Greatest Moments: If you enjoyed this speech by Andy Sperandeo, check out the speech, “Looking back at the founding of the NMRA,” by A. C. Kalmbach.

Like Andy, I met some great model railroaders because of military service. The Air Force sent me to Ellington AFB near Houston. I soon joined the San Jacinto Model Railroad Club and because of a Ft. Worth and Dallas tour set up by Gil Freitag, three of us had a late night visiting session with Cliff Robinson and were also over at Jack Leming’s house (also mentioned in #7). During a Lone Star regional convention in Houston, I found myself at Gil Freitag’s house at the same time John Allen made his visit. What great memories and there were many more great model railroaders that I met while in Texas.

Ken Vandevoort

Thank you for sharing this interesting speech. I am new to model railroading and wasn’t around during the times mentioned.

But Andy’s obvious love of the hobby and his enjoyment and knowledge of it comes through loud and clear and it was a joy to read it.