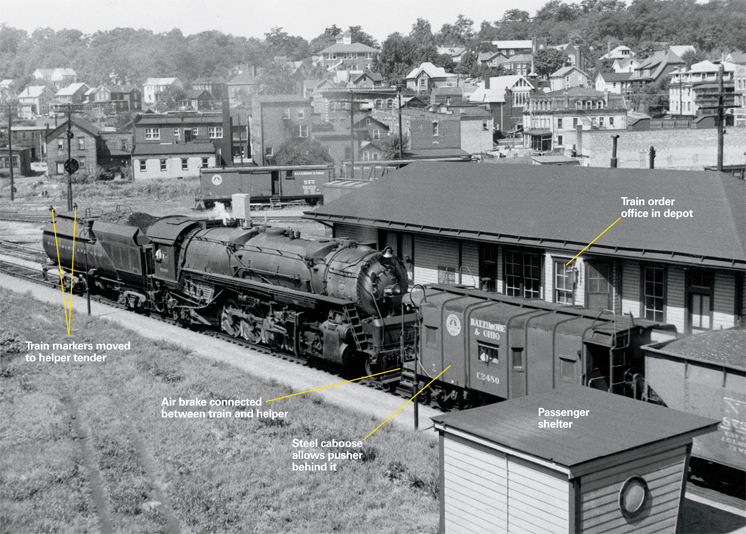

The lead engineer handled the train’s air brake while each helper engineer had an independent brake for just his engine. Two long blasts on the lead engine whistle (––) told the helper to release its brakes and proceed. The helper engineer repeated the two long blasts (––) in response and opened the throttle to push in the slack. Looking back, when the lead engineer saw or felt the slack bunch, he opened his throttle and began pulling the train. As the train moved along, the load was divided between the two so the lead engine was pulling the front portion and the helper was pushing the remainder.

The lead engineer controlled the train’s speed by how hard he was pulling, although most freight helpers moved relatively slowly. During the trip, the helper engineer paid close attention to how hard his engine was working and adjusted the throttle to maintain a steady push on the cars ahead. He also kept a close watch on his train line (air brake) pressure gauge.

A single whistle blast (o) indicated the lead engineer was going to stop, and a drop in the train line’s air pressure indicated a brake application was in progress. At that point, the helper engineer gradually reduced his throttle to keep working some steam to lubricate the cylinders, and then shut it off as the train slowed to a smooth stop.

Most railroads had specific safety rules covering the operation of a helper engine ahead or behind the caboose. In general, pushers could operate behind steel cabooses and wood cars that had heavy steel underframes. However, many of the older wood cabooses just weren’t built to handle the extreme forces of helper service, so any helper engine had to be cut in ahead of them.

good article helpers or bankers as they are better known in England were never coupled to the train as they would drop off at the top of the climb and return down the incline for their next duty if they were assisting on a single line section as on parts of the Somerset and Dorset they would be protected by a bank engine token for that section Charles Coleman England

Thanks, Jim. I've often wondered how steam engineers communicated in this early version of distributed power.

Marty Theissen

Jim

I always enjoy your articles that are well researched (likely many based on personal experience). They evidence your broad exposure to many aspects of railroading and illustrate the abundant experience you have had over the years. You have a credibility that is seldom attained by others.

George Baynton

The Rio Grande always put the caboose behind the helpers even if it was steel. This lasted until the end of the caboose. We used to watch the Rio Grande do this until the 90's. They cut the caboose off, and ran around it through the siding it and hooked it back on the train. this was done at Palmer Lake the top of the hill on the joint line in Colorado.

Jim L.