Q: What exactly is a switchback and how does it work? I originally thought it was a switching move backwards against the turnout (switch). But I read about switchbacks being used in maneuvering hills. I was also wondering if you could refer me to any back issues of MR where they have been used in a layout. – David Bellamy, Caledon, Ont.

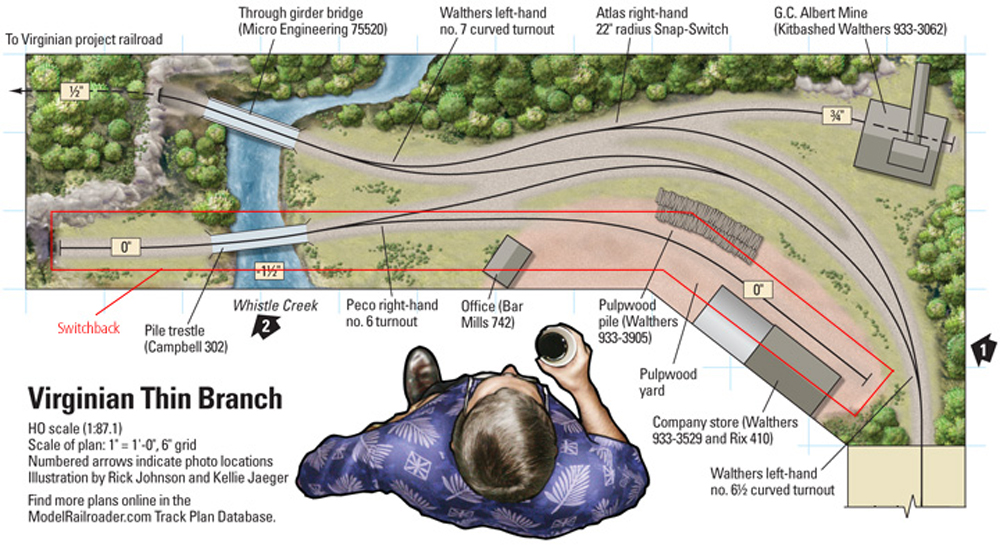

A: A switchback is a Z-shaped track arrangement, the end of which can only be accessed by pulling through a turnout onto a stub-ended track and then reversing through the other leg of the turnout. That description probably sounds more complicated than the actual track arrangement, but once you see one it will be clear. Take a look at the track plan of our 2013 Thin Branch project, below. The track enclosed in the red box is the switchback. Note how you can only get from the main line to the pulpwood yard spur by pulling onto the track that crosses Whistle Creek, lining the switch, and backing in. That’s what makes it a switchback. If the pulpwood track joined directly to the main or to a double-ended siding, then it wouldn’t be a switchback, it would just be a spur. The zig-zag is what makes it a switchback.

What we modelers might consider a fun operating challenge is a headache to full-size railroads, so they avoid switchbacks when they can. But, both on the prototype and on our layouts, switchbacks are sometimes necessary to maneuver track through difficult areas, like between buildings, inside sharp curves, or on steep grades. They can also be used to minimize the number of turnouts off the main when serving two or more nearby industries. But where you see switchbacks most often is on mining or logging roads that need to climb steep hillsides. A series of linked switchbacks that climb a grade step-wise can surmount a hill that would be too steep for a direct approach. You need a lot of length to make one of these work on your layout, since each stub end needs to be long enough to hold an entire train, and the track between the turnouts has to do all the work of gaining elevation. You can see an example of this technique in Anthony Richter’s track plan for the Fremont, Elkhorn & Missouri Valley in our June 2013 issue.

In fact, 2013 seems to have been a good year for switchbacks. In addition to Anthony’s freelanced track plan in June and our own Thin Branch in August, several other layouts and track plans that year included switchbacks. Look up Brian Glock’s Sugar Valley & Sweetwater Railway in March’s issue, Lance Mindheim’s CSX Miami Spur in December, and Tom McRae’s Lake Nipigon Northern track plan in April.

Send us your questions

Do you have a question about model railroading you’d like to see answered in Ask MR? Send it to associate editor Steven Otte at AskMR@MRmag.com.