Photograph by R. P. Morris

History of the Central Railroad of New Jersey

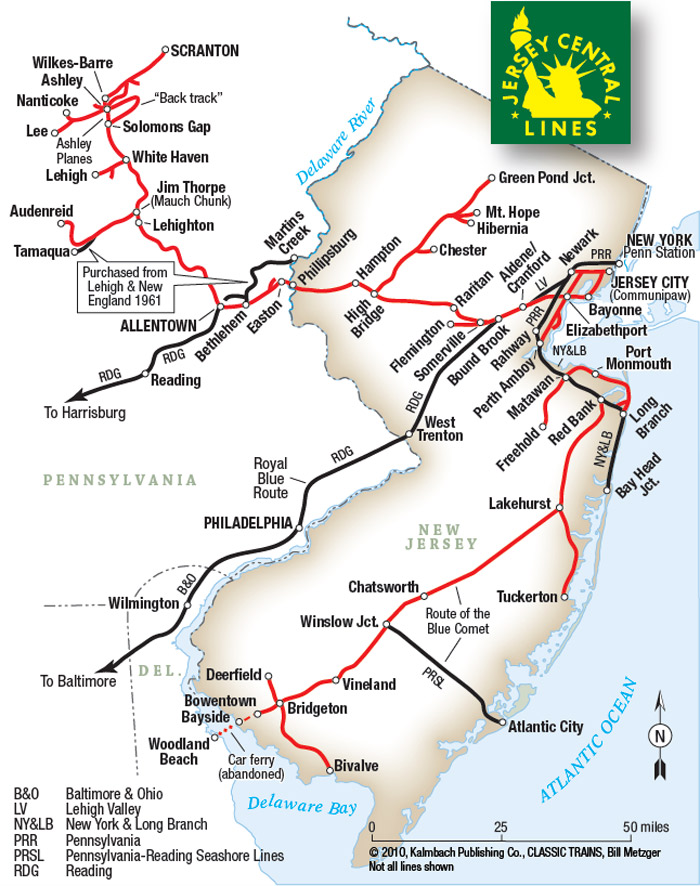

At its peak, the Central Railroad of New Jersey, the self-proclaimed “Big Little Railroad,” operated only about 700 route-miles, but in keeping with its densely populated region, totaled over 1,900 miles of track, two-thirds in New Jersey. CNJ’s Central Division extended from Jersey City to Phillipsburg, on the Delaware River. The Lehigh & Susquehanna Division (later Central Railroad of Pennsylvania, then the Penn Division) went west from Easton, Pa., to Allentown, then north to Wilkes-Barre and Scranton. The Southern Division, from Red Bank to Bridgeton/Bayside, was reached from Elizabethport via CNJ’s Perth Amboy Branch and the New York & Long Branch.

Although “little” in geographic span — it’s just 191 miles from Jersey City to Scranton — CNJ was “big” in traffic density. Between Jersey City and Raritan, 35 miles of commuter territory, four to six main tracks handled 300 daily commuter trains carrying 35,000 riders plus local freights, longer-distance passenger and freight trains, and, east of Bound Brook Junction, through Baltimore & Ohio/Reading traffic from Philadelphia and beyond.

Origins in 1836

CNJ’s origins trace to the Elizabethtown & Somerville, which opened in 1836 and soon extended via Plainfield and Bound Brook to Somerville. The Somerville & Easton began service between Somerville and White House in 1848 and bought E&S in 1849; six days later, the companies merged as the Central Railroad Company of New Jersey.

In 1852 the line reached Phillipsburg, where the Lehigh Valley Railroad delivered anthracite coal. In 1857, Delaware, Lackawanna & Western connected with CNJ at Hampton, and CNJ laid a third rail east to Elizabethport’s piers to accommodate DL&W’s 6-foot-gauge cars; CNJ also bought nine broad-gauge locomotives. In 1867, Lehigh Coal & Navigation’s Lehigh & Susquehanna Railroad connected to CNJ at Phillipsburg, and for a while CNJ was the tidewater connection for three anthracite roads.

Ferries to New York

CNJ ran passenger ferry service between Elizabethport and New York City into 1864, when it opened a passenger terminal in the Communipaw section of Jersey City and, to reach it, a mile-long drawbridge over Newark Bay between “E’port” and Bayonne. In 1876, CNJ and the Delaware & Bound Brook (later part of the Reading) began through service between Jersey City and Philadelphia. From 1886 till 1958, B&O passenger trains from Pittsburgh and the west used this RDG/CNJ route to reach New York City. B&O symbol freights ran into the 1970s.

The High Bridge & Longwood Valley opened between High Bridge and Rockaway in 1876, and within two years it became the High Bridge Branch as CNJ absorbed several small iron-ore roads in northern New Jersey to feed regional steel mills; others included the Dover & Rockaway and the Odgen Mine. In 1930, CNJ acquired the Wharton & Northern and the Mount Hope Mineral railroads.

Meanwhile, to the south and west

The Raritan & Delaware Bay was chartered in 1854 as part of a scheme with Delmarva Peninsula carriers to form the New York & Norfolk Air Line Railroad, a rail and steamship route between New York and Norfolk, Va. R&DB began in 1860 via steamboat between New York and Port Monmouth and train service to Red Bank. By late 1862, the road extended 64 miles to a Camden & Atlantic connection; R&DB re-incorporated as the New Jersey Southern in 1870. Vineland Railway opened in 1871 between the C&A at Winslow south through Vineland and Bridgeton to Bayside on Delaware Bay, where it received maritime fruit traffic.

NJS leased the Vineland in 1872, and Jay Gould soon controlled both in a scheme to link with Baltimore and the B&O via Delmarva. Resolution of a rate war between B&O and PRR in 1874 ended B&O’s interest in Gould’s lines, which entered foreclosure proceedings. A trustee ran NJS until leasing it to the New York & Long Branch, a CNJ proxy, in 1879. Reorganized as the New Jersey Southern Railway in 1880, it later would become CNJ’s Southern Division. While coal, cement, chemicals, and manufactured commodities dominated on other divisions, the Southern Division originated produce, sand, gravel, oysters, glassware, and eggs.

In 1873, NY&LB granted exclusive operating rights to CNJ. Service began between Perth Amboy and Long Branch in 1875, and by ’82 it extended through Ocean Beach (Belmar), Sea Girt, and Point Pleasant to Bay Head Junction. PRR threatened to build a parallel line, but an 1888 compromise granted both carriers rights on NY&LB, with CNJ handling the freight service. NJS got trackage rights between Red Bank and CNJ’s Perth Amboy Branch at Perth Amboy.

CNJ entered the anthracite region in 1871 with a 999-year lease of LC&N’s Lehigh & Susquehanna, which along with the inclined planes at Ashley opened in 1843 from the White Haven terminus of LC&N’s Lehigh Canal to the North Branch Canal at Wilkes-Barre. LC&N was authorized in 1863 to extend L&S from White Haven to Mauch Chunk to replace the flood-ravaged canal, and in 1864 began building to Easton to compete with the parallel LV. Service began in 1867, the same year the “Back Track” opened. This was a 12½-mile conventional railroad between Ashley and Solomon’s Gap, supplementing the Ashley Planes by carrying passengers and westbound freight while the Planes hoisted eastbound anthracite.

Photograph by Jim McClellan

Anthracite and the Blue Comet

CNJ’s evolution from tidewater connection to competing anthracite road coincided with LV and DL&W developing their own routes to New York Harbor. CNJ originally based its Pennsylvania operations in Mauch Chunk (now called Jim Thorpe). Narrow-gauge “lokies” worked the Wanamie Colliery on the Nanticoke Branch until 1967, and CNJ hauled the anthracite to Ashley’s Huber Breaker. In 1892, Central States Dispatch, a fast freight route on B&O, Western Maryland, RDG, CNJ, Lehigh & Hudson River, and New Haven, commenced via Allentown Yard.

In 1893, America’s first automatic, motor-operated semaphore signal was installed on CNJ at Black Dan’s Cut east of Phillipsburg. Installation of twin McMyler car dumpers at Pier 18 in Jersey City in 1919 created CNJ’s foremost destination for anthracite and bituminous coal into the 1960s. In 1925, what is regarded as America’s first successful commercial diesel locomotive, CNJ 1000, a 300 h.p. box-cab, began a 27-year assignment at Bronx Terminal. The bridge over Newark Bay was replaced in 1926 by a 1.4-mile, 4-track, 2-span, lift-type drawbridge. In the 1930s, one of the country’s most modern traffic control towers was installed at Elizabethport to control the convergence of the multi-track Central Division main with the Newark and Perth Amboy branches. E’port also hosted CNJ’s main shops.

Two Blue Comet consists, Packard blue with gold lettering and window bands of Jersey cream, in 1929 introduced luxury coach service at no extra charge between Jersey City and Atlantic City. Later that year, The Bullet debuted similar service between Jersey City and Wilkes-Barre. Specially painted Pacifics handled both: royal and Packard blue with gold striping and lettering for the Comet and dark olive with gold striping and chromium trim for The Bullet. The latter ran only two years, but the Comet lasted until 1941.

CNJ entered a 10-year bankruptcy in 1939 while controlled by the Reading, which in turn was controlled by B&O. During World War II, the German submarine menace diverted eastbound oil products from tanker to tank car, and CNJ delivered up to 1,000 loads a day, half the New York area’s requirement, until pipelines were built. In 1944 CNJ became “Jersey Central Lines” and adopted the Statue of Liberty emblem.

Central Railroad of Pennsylvania was established in 1946 in a vain effort to shield Pennsylvania assets from heavy New Jersey taxation; it was dissolved December 31, 1952, succeeded by the Pennsylvania Division January 1, 1953. In 1961 when Lehigh & New England quit, CNJ bought the 40 miles of its Pennsylvania trackage generating cement and anthracite loads.

Photograph by Bob Wilt, J. David Ingles collection

Camelbacks and Baldwin diesels

Camelback 2-8-0s and 4-8-0s yielded mainline freight assignments to 86 heavy 2-8-2s in 1918–25; Pacifics supplemented Camelback 4-6-0s in passenger service, and huge 0-8-0s worked Pennsylvania yards. In 1946, the only double-cab diesels in the U.S., six 2,000 h.p. Baldwins, replaced 4-6-2s between Mauch Chunk and Jersey City. The 1947 arrival of CNJ’s first road freight diesels, five A-B-A sets each of EMD F3s and Baldwin DR-4-4-1500 “baby faces,” bumped many 2-8-2s, and on July 1, 1948, the Ashley Planes closed as diesels handled all freight on the Back Track at half the cost. Freights were dieselized in 1953 and passenger trains in ’54. Twelve SD35s in 1965, painted the dark green that had replaced an early blue-and-tangerine on road diesels, were CNJ’s last new-locomotive purchase, while ally B&O provided nine SD40s in 1967.

Cancellation of mail contracts in 1965 brought discontinuance of 18 CNJ passenger trains systemwide. Erstwhile competitors CNJ and LV, battling to survive, sought to reduce costs on parallel Pennsylvania routes, and, with the Reading, implemented a coordination program in November 1965. LV and Reading abandoned small yards and relocated into CNJ’s expanded Allentown Yard, while new connections at South Bethlehem and Lehighton permitted LV to run on CNJ Bethlehem–Lehighton. In 1967, CNJ re-entered bankruptcy and dropped its last non-commuter passenger trains (Allentown–Jersey City).

New Jersey DOT implemented the “Aldene Plan” in April 1967 to reduce passenger operating deficits. A new connection from CNJ up an embankment to LV’s main line at Aldene diverted CNJ trains from the Jersey City terminal to PRR’s station in Newark and eliminated CNJ’s Hudson River ferry service. A shuttle train preserved service between Cranford and Bayonne. Operational requirements of the Aldene Plan also caused CNJ to introduce push-pull trains with control cars converted from 1920s-era coaches. In November 1968, EMD delivered 13 GP40Ps, 3671–3683 (elongated GP40s with a steam generator), which replaced 13 FM Train Masters in passenger service. Numbered in B&O’s system, they were painted blue, visual evidence of B&O’s role in financing them.

CNJ’s 1971 “Blue Print for Survival” outlined steps to restore profitability, including abandonment of Pennsylvania operations. CNJ left Pennsylvania March 31, 1972, excluding its ex-L&NE trackage. LV assumed CNJ’s operations, expecting to keep the through traffic to/from the Erie Lackawanna, but CNJ began trains ES99/SE98 with EL between Elizabethport and Scranton via a new connection on the High Bridge Branch. LV and Reading took over CNJ’s ex-L&NE lines in January 1975. In ’72, CNJ had adopted a red with white trim livery that was applied to some RS3s and GP7s plus SD40 3067, dubbed “The Red Baron.” It was all in vain, of course, as a federal court in 1974 ruled CNJ, LV, RDG, and PC incapable of reorganization; all were absorbed into Conrail on April 1, 1976.

I grew up in Scranton in the 60’s, etc. knowing one thing about CNJ – they had something of a presence at some point because we drove past their old abandoned freight terminal many times over the years. I had no idea of how extensive a network they had in PA.

Today, I wonder how much if any of their old Scranton area trackage is in use – railroading in Scranton is far more alive than it was when I left Scranton in the late 70’s. Tracks I never saw in use then are used today.

I live in Bridgewater, between Bound Brook and Somerville, which is now a NJ Transit Station. I’ve seen the pictures, but whenever I ride a NJT train on what was once CNJ I have a hard imaging what it was like in the days of a 4-track main. It really must have been something back in the heyday of CNJ.

Mario