Specifically, on one night shift in the early 1950s in Benwood, 5 miles south of Wheeling, W.Va., along the Ohio River, our yard crew witnessed a dramatic sight that few people have seen. I was fireman on our engine, an old 0-8-0.

Our vantage point was on the high part of a grade of a large reversing loop. Beyond the upper edge of the yard and the reversing loop was a steel mill, and high above the entrance to the loop was a long, elevated approach to the B&O bridge spanning the Ohio River. The elevation was necessary because the Ohio is a navigable river. Older bridges spanning navigable waterways had to be high enough to clear boats (years before, steamboats with tall stacks) during periods of high water.

The large, 0.6-mile reversing loop was used primarily for westbound passenger trains out of Wheeling, headed for Cleveland, Chicago, or Cincinnati. They would depart the Wheeling station, travel 4.4 miles to the south, and enter the loop. At the upper end of the loop, at the edge of Benwood Yard, the trains would pass through two double-slip switches and go upgrade past the small Benwood station. At this point the train would have completed a 180-degree turn.

Continuing upgrade on elevated tracks, it would cross high over the entrance to the reversing loop and travel in a northwesterly direction until it reached the bridge over the Ohio River. (B&O’s passenger station at Bellaire, Ohio, at the west end of the bridge, was up on the third floor of the building.)

About 3 a.m. on this early summer night, the yardmaster at the Upper Yard Office told our crew foreman that a boxcar containing valuable machinery had to be turned because it could be unloaded from only one side. He also said that once that was done, to stay out of the yard for a short time because space was needed for an important incoming freight train.

We coupled onto the boxcar, backed out of the yard onto a main track and through the first double-slip switch. Once clear, we went forward and up and around the top of the loop, then stopped on the high point of the loop. A brakeman set the handbrakes on the boxcar, and then uncoupled it from the front of our 0-8-0.

We backed around, went through the slip switch, set it for the proper direction, and then backed down the southbound main track several hundred yards until we came to the switch at the bottom of the loop. There we stopped; the switch was thrown, and we went up and around, slowed, and coupled onto the boxcar from the other end. Once we had backed down through the loop and entered the yard again, the boxcar would be properly turned.

We’d been told to stay out of the yard for a while, and since no passenger trains were scheduled to use the loop for hours, we could park there. The engineer and I hauled out our lunch buckets and enjoyed a sandwich and some coffee. The rest of the crew sat on the ends of ties and relaxed. It was a dark, moonless night, and, oddly enough, tonight there was no fog moving in from the river.

Soon a long freight train powered by a big 7100-series 2-8-8-0 Mallet chuffed slowly across the bridge from Ohio and started down the long, curved track that led past Benwood station and into the upper end of the yard. During the warm months, coal moved out of the north-central West Virginia coalfields and up the Ohio River valley to Benwood, crossed the river, and was hauled upgrade to Holloway, Ohio. From there, in several stages, the coal was taken to the transloading docks on Lake Erie at Lorain, Ohio, to be transported by lake boat to northern and western markets. B&O trains would bring iron ore and other raw materials from Lake Erie down to the steel mills in the Wheeling area. As long as the Great Lakes ports remained open, the B&O carried loads both ways.

The train we were waiting for was returning with a long string of gondolas loaded with manganese, an ore needed for certain types of special steel. Manganese is extremely heavy — in standard gondolas, it was loaded only above the trucks at either end of the car. From a distance, the only indication the cars were loaded were small mounds of ore visible above the sides of the cars.

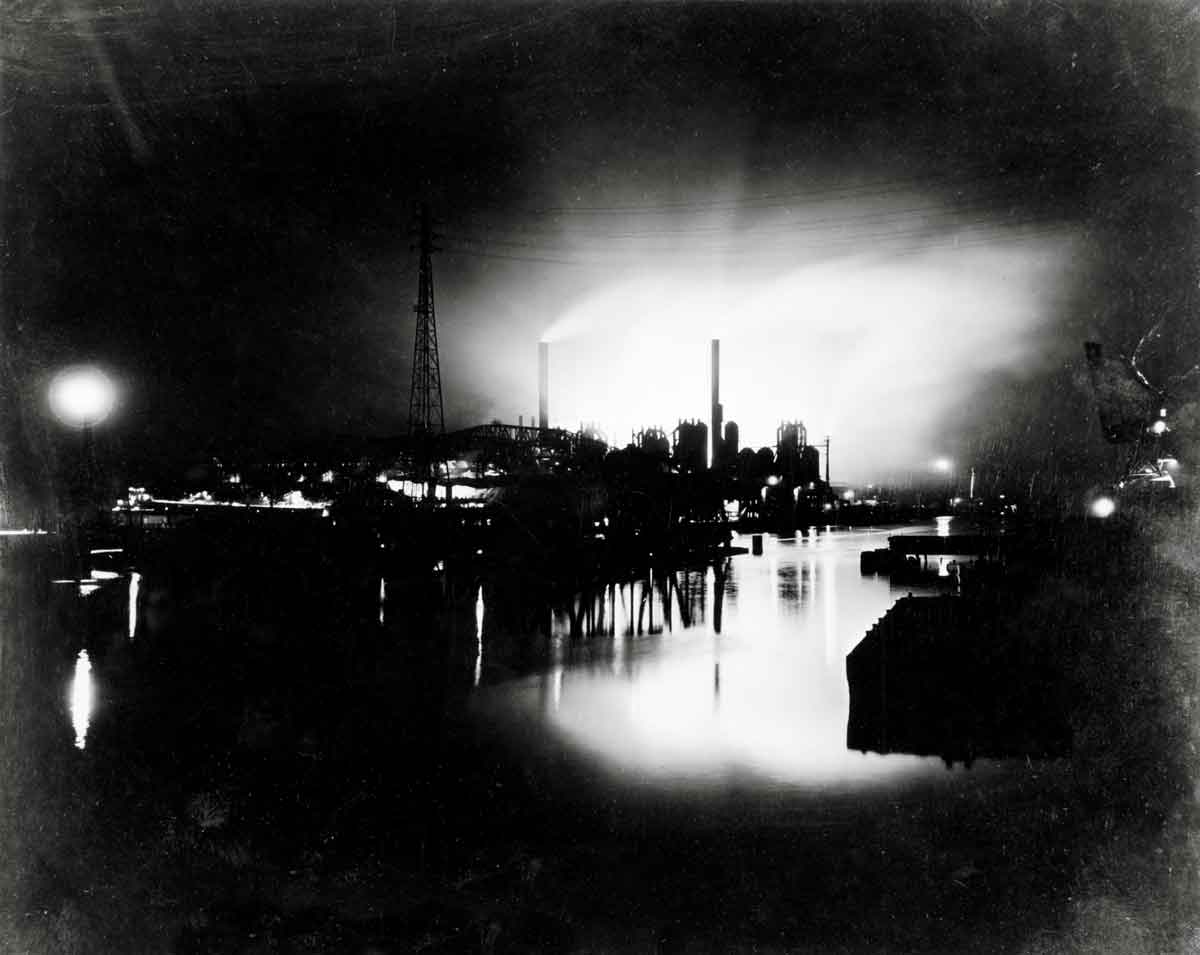

Just as the train on the elevated track came between us and the dim lights of the Benwood steel plant, a huge red-orange light lit up the night sky. The immense glare lit the lower side of the steel mill, Benwood Yard, and nearby houses on both sides of the river.

The steel company used the open-hearth process to make steel. Fourth of July fireworks in a big city would appear anemic when compared to the Technicolor operations at an open-hearth furnace.

The demand for steel during World War II and for years following was insatiable — production went on 24 hours a day. Open-hearth operations were hardly noticeable during daylight hours, but at night they produced spectacular displays of light.

Our entire crew watched in silent appreciation as the train with its loads of manganese ore was outlined against the glare from the plant where the molten steel was being poured. The industrial strength of our region more than 60 years ago was summed up in that awesome view of the silhouetted train passing in front of the pyrotechnic display at the steel mill.

It was a stirring sight, long to be remembered.

First published in Summer 2010 Classic Trains magazine.

Learn more about railroad history by signing up for the Classic Trains e-mail newsletter. It’s a free monthly e-mail devoted to the golden years of railroading.

This is really interesting on several levels. The references to nighttime in the rail yards brings back numerous memories: of the switch lamps, fusees, lantern signals, hobos, a late night lunch in a caboose, etc. So much has already disappeared of the vast infrastructure once necessary for both passenger operations and switching activity. And it is enjoyable to read about the mills; the prevalence of which was simply amazing. Their presence was unforgettable, as your piece so eloquently and enjoyably relates.

Terrific! I felt like I was sitting in the cab with the writer. I had read the article in the original publication but forgot about it. It was even better the second time around. Thanks.

What a great article. I rode the B&O veterans train to Chippewa Lake that ran from Benwood to the Lake, up through Holloway, Dover and Massillon to Medina, OH. Been on the loop many times as well as the small station. Wheeling Steel owned the mill, and I had a great Aunt who remembered when it was built in a field and later demolished. We could sit on her porch in the Summer on Marshall Street and hear the switching that went on in the Benwood Yard, day and night. Freights and passenger trains would come off of the loop and run below grade to the beautiful Wheeling passenger station which is now a college, and went north to Pittsburgh. Thanks for your reminisces.