What do switch crews know? If you want to know how trains operate smoothly, ask the experts — the railroaders themselves.

Things happen for a reason in the real world. Take switch-stand locations. Railroads hate to have brakemen crossing and recrossing tracks. It’s dangerous. It’s far safer to put all the switch stands on one side or the other. The engineer’s side is best (in cases where that can be known). Railroads also generally align turnouts so that most traffic goes straight and, ideally, prefer to locate industry spurs off a siding (the railroad version of an access road).

Railroads need to allow space for switchmen and brakemen to do their work so the roadbed is extended out to 10 feet or so from the track centerline to serve as a walking surface around switch stands and derail stands. (This gravel pad is called “headblock dressing” – the headblocks are the long ties where switch stands are mounted.)

Room is also allowed for vehicles to drive alongside the tracks in areas where there will be crew changes or the need for signal maintenance.

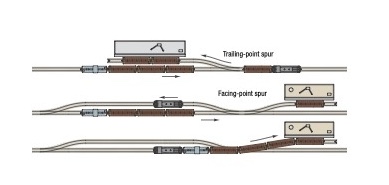

Given any sort of choice at all in picking up or setting out cars, a crew will usually opt for trailing-point pickups and setouts (see the top example in the diagram above). Runaround moves needed to handle cars through a facing point turnout take a lot of extra time. Some locals or “mainline locals” will only switch trailing point industries, leaving the others for their return trip (or for their counterpart that goes in the opposite direction). Rear-end pickups take more time and are more dangerous because the engineer can’t tell if the crew on the ground are in a safe position.

Given any sort of choice at all in picking up or setting out cars, a crew will usually opt for trailing-point pickups and setouts (see the top example in the diagram above). Runaround moves needed to handle cars through a facing point turnout take a lot of extra time. Some locals or “mainline locals” will only switch trailing point industries, leaving the others for their return trip (or for their counterpart that goes in the opposite direction). Rear-end pickups take more time and are more dangerous because the engineer can’t tell if the crew on the ground are in a safe position.

When the work is done, an engineer will often back up the entire train to retrieve a brakeman (if there isn’t a caboose), because that’s much faster than waiting while he walks the length of the train to the locomotive. This happens only in areas where the train doesn’t have to back across a grade crossing in the process. Why do crews place so much emphasis on saving time? Partly because there’s a certain amount of pride involved in performing a difficult job with smooth efficiency. Not infrequently, a crew may be working quickly because the “track-and-time” allowance from the dispatcher is due to expire, and with higher-priority trains due, they can’t expect an extension.

But mostly it’s about money. Mainline crews are paid by the mile, not by the hour, so they tend to work as fast as the rules and safe operation allows. Yard crews are paid by the shift, but they also generally work as fast as possible in hopes of completing their assigned tasks an hour or two early and being allowed to go home (an “early quit”).

Railroaders also know when to take it slow. The guys over in the yard would love an early quit, but they’re coupling cars at not much more than walking speed. A hard coupling can damage equipment and cargo. On the main line, a passenger train has slowed to a crawl because a track inspector has spotted a problem and imposed a slow order on a section of track. Down the line a bit, an engine idles outside of a warehouse while a switchman walks inside to make sure no one is working on or near the car they’re supposed to pick up and that the cargos are secured inside any loaded cars that must be moved.

What do switch crews know? They know that a properly designed railroad operates like a dream, while an awkward track arrangement is like a headache that never goes away. They understand when to work quickly and when to exercise caution. Most of all, they know that true efficiency depends on a perfectly executed sequence of moves.