By 1840, the nation had 2,800 miles of railroad track. In his book American Notes, novelist Charles Dickens captured the flavor of an 1842 trip on the Boston & Lowell Railroad. “On it whirls headlong, dives through the woods again, emerges in the light, clatters over frail arches, rumbles upon the heavy ground, shoots beneath a wooden bridge which intercepts the light for a second like a wink, suddenly awakens all the slumbering echoes in the main street of a large town, and dashes on haphazard, pell-mell, neck-or-nothing, down the middle of the road.”

As the years rolled on, passenger trains became faster, safer, and more comfortable. In the 50 years between 1865 and 1916, the American rail network grew from 35,000 miles to more than 250,000 miles. Every town of consequence had passenger service, and you could take a train from anywhere to anywhere.In 1902, New York Central launched its luxurious 20th Century Limited between New York City and Chicago. Some years later, author Lucius Beebe would write this: “Showpiece, legend, article of railroad faith, the 20th Century Limited is a national institution, moving with the exactitude of sidereal time, as implacable as fate.”

When the United States entered World War I in 1917, the nation’s railroads were ill-prepared for a sudden 30 percent increase in business. Debt-laden and over-regulated, the system was on the verge of chaos when President Woodrow Wilson ordered the Federal government to take control of 90 of the largest railroads. By the time railroads returned to private control in 1920, a new form of transportation had caught the public’s fancy. In that year automobile registrations passed the 8 million mark. In 1928, rail passenger volume was 33 percent lower than it had been in 1920, and automobile registrations topped 21 million.

The Great Depression compounded the financial difficulties already facing the railroads. By 1933, rail passenger-miles dipped to a third of the 1920 level, and some railroads were forced into receivership. But there were bright spots in the gloom. In 1935, the Chicago & North Western introduced its 400, a train named after its schedule, which allowed just 400 minutes to cover the 400 miles between Chicago and Minnesota’s Twin Cities. North Western’s rivals, the Chicago, Burlington & Quincy and the Milwaukee Road, fielded fast trains of their own.

In the East, New York Central and Pennsylvania Railroad, normally the most bitter of competitors, jointly placed orders for radically new, lightweight, streamlined, air-conditioned passenger cars to re-equip their flagship trains. The Pennsylvania’s Broadway Limited and the NYC’s 20th Century Limited both entered service on June 15, 1938, with identical 16-hour schedules between New York City and Chicago.

The new trains were undeniably luxurious — the Century even had a barbershop. But the railroads no longer had a monopoly on transportation. Highways were improving and millions of cars, trucks, and buses were using them.

Railroads threw themselves wholeheartedly into the war effort in 1941. Freight and passenger business doubled the levels seen during World War I, yet there was no repeat of the confusion of the earlier war, and the government remained on the sidelines.

The boom that never happened

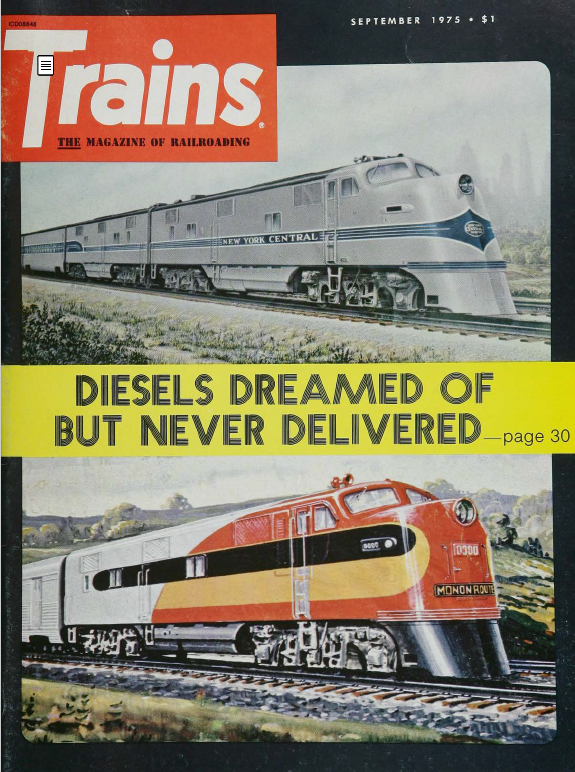

The end of the war found the railroads ready for a new era. Orders were placed for billions of dollars of new cars and locomotives, including vast numbers of diesel locomotives to replace steam engines. The optimism of the railroad companies extended to passenger service as well. Drab and worn prewar passenger cars were swiftly replaced by gleaming stainless-steel streamliners. A new era in rail travel was at hand, but it would be short-lived.

On October 26, 1958, the Boeing 707 took to the air on its first commercial flight, ushering in the age of jet-powered commercial airline travel. The Highway Act of 1956 authorized $25 billion to build Interstate highways. These developments hit rail travel hard.

By 1960, rail passenger counts were at 20 percent of 1944 levels, and railroads reported an annual passenger service deficit of $300 million. When the Century stopped running in 1967, the railroad’s president said it was the riders, not the company, that had abandoned the train.

With ridership dwindling and no end to the red ink in sight, the Federal government approved the creation of a national passenger rail system in 1970. Amtrak took over the operation of most passenger service in 1971, although a few railroads opted out of the national system and continued to field their own trains for several more years. Amtrak kept a semblance of rail passenger service running and even introduced a few innovations of its own, but the grand era of the streamliner was over.

So where’s the story about what happened to that equipment? Gone to Mexico? Saudi Arabia? Rusting away on a siding running out the equipment trusts? Commuter service like the Roger Williams? That’s what I thought this article was going to be rather than yet another rehashing of the demise of the American psgr train.

So do a piece on where those post WWII streamliners went.

“What happened to the great passenger trains” in North America? They are gone but never forgotten! As we all know, it is sadly true that, railfan or not, most of the passengers in North America had abandoned trains long ago due to the whopping impact of Jet Age and highways… Note that the revolutionary Jet Age similarly brought an end to the uniquely luxurious and comfortable regular ocean liner crossings between North America and Europe.

Dr. Güntürk Üstün

“Railroading’s a lifetime proposition.” So is railfanning!

Dr. Güntürk Üstün