Editors note: For more on the Rhätishe Bahn and its heritage fleet, including Switzerland’s one-of-a-kind snowplow, see the July 2025 issue of Trains Magazine.

PONTRESINA, Switzerland — Markus Zaugg, head of rolling stock for the Rhätische Bahn, is leading an informal tour of the railroad’s shop building in the mountain village of Pontresina. The town near St. Moritz is the southernmost connection between the rest of the RhB and its Bernina Line — completed as an independent railroad in 1910, but absorbed by the RhB in 1943. This independent beginning is why the Bernina Line uses a 1,000-volt DC electrical system, compared to the 11,000 volt AC for the rest of the railroad.

“A lot of the vehicles for the Bernina Line are one of a kind,” notes Zaugg. This reflects both that uncommon electrification and the demands created by a line that reaches 7,932 feet (2,253 meters), the highest railway crossing in Europe. “They’re specially made for this purpose and have no direct comparison to any other vehicles in the world.”

He says this as we look at the piece of rolling stock that may be the ultimate illustration of this observation.

In front of us is the world’s only self-propelled steam rotary snowplow: Xrot 9213, a six-cylinder superheated 0-6-6-0, using four cylinders to propel the machine and two to run the rotary. It was built in Winterthur in 1910 by SLM, the Swiss Locomotive and Machine Works. (Conveniently, the English translation has the same initials as the German name, Schweizerische Lokomotiv und Maschinenfabrik.) The idea of just calling it a snowplow apparently offended the builders.

“The definition from the works for this engine,” says Zaugg, “is ‘It’s a steam locomotive with the option to plow snow.’”

Along with his primary job, Zaugg oversees the extensive RhB heritage fleet. Our visit to the shop on this quiet September Saturday is because, during an earlier conversation, he immediately chose the snowplow when I asked if he had a favorite piece of heritage equipment.

“Such a unique engine,” he said then, “and it has its own soul. That’s my favorite, favorite vehicle.”

A second such plow built in 1912 also survives, but not in operating condition. It is a static display at the Blonay-Chamby Railway, a heritage line in western Switzerland.

The coal-fired rotary in front of us, however, is most definitely functional. A little more than a month before my visit, the plow had made its first test runs after a three-year restoration project. “I was there and made all the test runs,” Zaugg says. “Ah, it was beautiful. It worked so good.”

The plow’s longevity in part reflects its carefully formulated design. The cylinders for propulsion are mounted between the two sets of drivers; that pushes the first set of drivers closer to the front of the machine, keeping the rotary aligned with the track. The drive shaft for the plow can be heated, “so it will heat the propeller up just a little bit, so it won’t freeze in the housing,” Zaugg says. And that rotary propeller itself was built to last; the blades have never been replaced. “There are some nicks here and there,” he says, “but it’s still original. It’s so strong; it’s absolutely impossible to destroy.” He recalls hearing a grinding noise while clearing an avalanche. It was the sound of trees within the snow being chopped up by the blades.

As much as the plow was built to last, its current flawless condition also reflects the focused attention of a now-retired craftsman on the RhB shop staff.

“This was his last piece of work,” Zaugg said. “During restructuring the organization of all the workships, he kind of lost his job. … At the same time, it came up that this engine needs a revision, and he knows this engine like nobody else. So we said, hey, look, you’ve got three years now, and then you are retired, so just do this. And he put all this heart and all his sweat into this, and he made such a beauty.

“He was on the test run, and everything worked so well. … It’s a one-shot perfection, absolutely perfect. And after the day, and everything was finished, we were going into the restaurant to have a beer and celebrate a little, and he was in tears. He was so proud.”

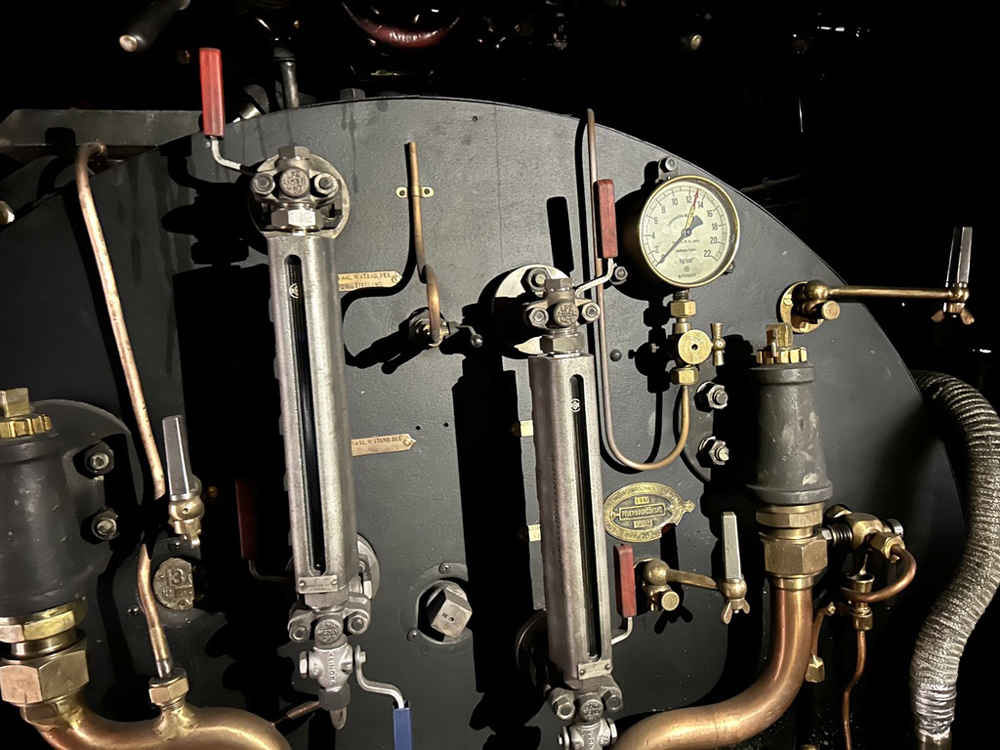

His pride in his work shows when you step into the carbody. Every piece of hardware looks as if is brand new, rather than being on a 115-year-old piece of machinery. A perfect example is a toolbox mounted on one of the sidewalls that would be the envy of any mechanic; every tool is spotless and has a very specific spot where it is attached. “Everything in its place,” says Zaugg with satisfaction. “Every bolt and everything, it has a tool, here on the engine. So you don’t need to bring any additional tools when you go in service.”

While it only takes an engineer (driver, in the European terminology) and fireman to run the plow — at least when moving it from place to place — during actual plowing work, operation is a four-person operation: In the front are the driver and an assistant who watches the track ahead — “the eyes of the driver, so to speak,” says Zaugg, “because when you drive and you go through the snow, you just listen to the engine and watch how the snow goes, and you have no idea what comes in front.” At the rear are the fireman and someone who communicates with the driver.

While that crew is equipped with radios, the reality is that they do their communicating the old-fashioned way. “It’s very difficult to use [radios] because it’s so noisy in here and you can’t hear,” Zaugg says. “So we do it mostly with whistle signals. It’s the easiest way. You have just to be a good team, and then it works fine.”

Top speed when the rotary is at work is about 6 miles an hour. That may not sound fast, but it’s twice the speed of the RhB’s modern rotaries. “You can only go as fast as the [current] rotaries can take in the snow,” Zaugg says. “That’s why you have to drive so slowly. With this kind of system [for the steam rotary], you just push in the snow, and if it’s not able to take in the snow, you just push it forward and take it in later.”

And while it is self-propelled, that doesn’t mean it sometimes doesn’t get help from another locomotive.

“If you have to plow snow away on a 7% grade, you need a vehicle that pushes you also,” he says. “But grades of 3.5% or 4%, up to 2 meters of snow, it’s no problem. You can drive through it; the engine has enough power for that.”

In the plow’s long history, there has been precisely one change from its original design. And it took a tragedy to bring that about.

“The safety valves — they were originally sitting directly on the boiler inside here, and it has just a small window for the steam that could go out,” Zaugg says. “And then there was an accident, an avalanche that threw the machine on the side, and the safety valve got cut off and the boiler just emptied here inside, and it burned up about six people that were in here.

“So after this accident, they put the safety valves on the roof, (added) additional piping and put it on the roof. That was the only change in the lifespan of the engine.”

That lifespan, from a working standpoint, was even longer than you might suspect. The plow almost made it to the 2020s on the active roster.

“Only since six years [ago] it’s officially a historic engine,” Zaugg says. “’Til then, we had it for an emergency backup, and until about 10 years ago, we had it fired up in October and shut it down in April again. It was warm the whole winter, and we used it about 10 to 12 times during the winter season.”

Today, the rotary runs about twice a year for railfan excursions. At the time of my visit, plans for operation in 2025 were uncertain, but Zaugg says it will definitely run in 2026.

“You can buy a ticket, it’s around 250 to 300 dollars, but there are only about 50 places. They go very fast,” he says. “This is publicized on the internet, and the home page from the Rhaetian Railway. It is a very unique experience.”

Of course, there’s another option: you can charter your own excursion. Zaugg was not sure what that would cost, but estimates it’s double the cost of a normal steam excursion because of the high manpower requirements. “For whole-day operation, about 15,000 to 20,000?” he guesses. “But if you get enough people ….”

Well, you can have a genuinely one-of-a-kind experience.

And if you do, let me know, will you?