BNSF’s Truxton Flyover project

Truxton, Ariz., is not exactly one of the metropolitan centers of the American Southwest.

“Population: very small,” says Craig Rasmussen, BNSF Railway assistant vice president, engineering services and structures.

Officially, as of the 2020 census, 104 people live in the hamlet 42 miles northeast of Kingman, Ariz., on U.S. Route 66. Remote and obscure though it may be, Truxton plays an oversized role in BNSF’s efforts to maintain traffic flows on its Southern Transcon, the former Santa Fe Railway route between Los Angeles and Chicago.

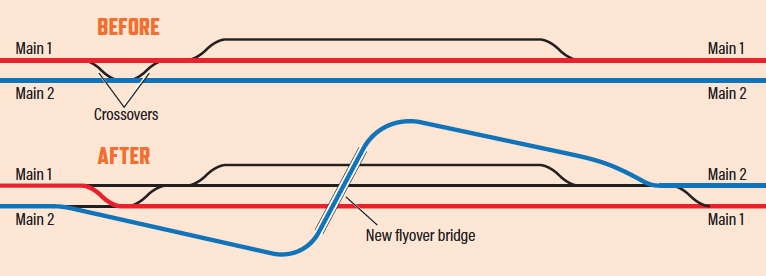

It is here that the railroad constructed its Truxton Natural Flyover, allowing trains to change main tracks to take advantage of more favorable grades when coming from Needles, Calif., while remaining properly aligned for refueling and inspections at the crew-change point in Belen, N.M.

“Eastbound trains have to be on the south track climbing through the canyons [in Western Arizona],” says Rasmussen, “and then they have to be over on the north track by the time they get to Belen.”

The flyover — which cost approximately $34 million — eliminates an estimated 35,000 at-grade crossover moves per year, and the accompanying operational disruptions. Rasmussen says it eliminates 900 operating conflicts a week — incidents when a train had to be stopped to allow another train to pass or cross over. Those added up to more than 17,000 hours of delays annually.

BNSF had “about a state and a half worth of railroad to deal with” in choosing the location, Rasmussen says, and looked at six potential sites. These were assessed according to four criteria: the ability to elevate one main line over the other; existing track geometry; the ability to minimize right-of-way (i.e., land) needs; and a spot where track speed was already lower, so trains didn’t lose time by slowing for the flyover. These criteria led the railroad to choose … not Truxton, but a location near Seligman, Ariz., which offered the best cost/benefit ratio.

“If you went out to this spot today, you would see this looks like a beautiful spot to build a natural crossover … You can see where, naturally, one main line could fly over the other one,” he says.

Flyover challenges

But the railroad did not own the required land. It belonged to Arizona’s Trust for Public Land and the Navajo Nation; the process of acquiring property from those two entities was complex and daunting enough that BNSF moved on to its second-choice site, Truxton.

There, it needed to acquire a 400-foot-wide by 1.8-mile-long strip of right of way from private owners and the federal Bureau of Land Management. To acquire that land, and expedite the permitting process, the project had to be designed to minimize the impact on the Truxton Wash, which runs through the site. While mostly dry, the area is subject to occasional torrential rains that can lead to water flows of up to 11,500 cubic feet per second — more than 5.1 million gallons per minute.

The project required five small culverts and one large double-arch culvert. The flyover bridge not only has to cross the railroad tracks below, but the wash area, and there are a number of measures to prevent erosion, including rip rap-lined bridge embankments, protective mats, and grouted slope protection at the end of the major culvert.

“From a structural standpoint,” says Audra Rogers, U.S. West Region Transit-Rail Sturctures Lead at AECOM, the project designer, “our goal was to minimize the impact to the jurisdictional waters for permitting purposes and also to accommodate the large hydraulic area of the wash, and deal with the rock depth and quality issues.”

The site’s geology posted challenges. The top soil is a sandy clay, requiring structures to be anchored to the underlying rock. But that topsoil extended to a depth of 50 feet in some areas. Over the 500-foot length of the arch culvert, the depth of the rock varied by up to 20 feet, and in highly unpredictable fashion, Rogers says: one supporting pile was 20 feet deep; the next, just 6 feet away, was only 7 feet.

The final design called for a 14,900 foot flyover, with 600,000 cubic yards of material brought in for the embankments leading to the 10-span bridge. Most of those are of a standard BNSF design; the center piece, providing 23 feet, 6 inches of clearance over the lower main line, is an 87 four-girden deck-plate steel span. Approaches to the bridge had to stay under the ruling grade for the area of 1.4%.

Ben Sullivan, project manager for builder Ames Construction, says the remote location brought its own challenges.

“We were about 45 minutes east of Kingman,” he says, “so some of our suppliers were a little leery to sign contracts. But our concrete supplier did a great job, without any issues. And the temperature in Arizona has a lot of highs and lows and varying temperatures, and we had a couple of mass concrete pours that we had to monitor.”

Flyover successes

The project required more than 100,000 man-hours of work, Sullivan points out, and was completed without any injuries, either on the part of the Ames team or BNSF workers. That, said Rasmussen, “is the gold standard, the benchmark of how we do projects anywhere.”

The flyover went from conception to completion in 24 months, another point of pride for Rasmussen, who says that underlines one of the advantages railroads have over other modes of transportation: the ability to “deliver capacity faster than the other modes can.”

Ultimately, though, the greatest significance is what the project means for the railroad and its customers.

“Every week, 900 fewer trains get stopped,” he says. “That’s capacity, that’s efficiency, that’s being friendly from an environmental standpoint and a fuel-consumption standpoint. And at the end of the day, it’s about our customers that are going to be able to better move their product.”

— David Lustig first wrote about the Truxton flyover in the February 2022 issue of Trains. This article includes details from that piece, and information from an American Railway Engineering and Maintenance-of-Way Association presentation by Rasmussen, Rogers, and Sullivan on Aug. 29, 2022.

Interesting that it has taken over 60 years to re-establish the flyover that was eliminated by construction of the Williams-Crookston cutoff and abandonment of the two separated mains on that segment in 1960. The pre-cutoff alignment had a flyover west of Ash Fork that put trains on the appropriate track for better grades. Santa Fe, and later BNSF, therefore had ample operational experience of the advantages procured by avoiding crossovers at grade in Winslow or wherever they could fit.

When did they break ground, and when was the new route turned over to BNSF?