Q: My father, who gave me my first train set in 1974, asked me a couple questions about steam locomotive power that I didn’t know the answers to, so I’m directing them to you. Which wheel configurations are better for pulling a train up a hill versus long freight loads a long distance, and why? Also, what is the relation between drive wheels and cylinders? — Peter Burris

A: The relationships between steam locomotive power and the locomotive’s moving parts are complicated. If they weren’t, there wouldn’t have been so many different cylinder, valve, firebox, boiler, and wheel combinations tried and built. But there are some general rules I can try to break down for you.

The wheel configurations of a steam locomotive come down to two factors: tractive effort and speed. The stronger the tractive effort (a.k.a. drawbar pull), the more cars the engine can pull. And the faster the engine can go, the faster those cars can get to their destinations. Unfortunately, there’s a direct tradeoff between the two factors. Larger drive wheels, which travel farther per revolution thanks to their larger circumference, make for a faster engine. Locomotives with smaller drive wheels, which have more mechanical advantage than large ones, pull harder — especially at low speeds, which is important when starting a heavy freight train — but move slower.

Think of a steam locomotive’s driver in terms of a lever. The axle is the fulcrum, the point where the drive rod meets the wheel is the effort, and the point where the wheel tread meets the rail is the load. The closer the effort is to the load, the more force is applied, but the load moves a shorter distance. Conversely, with a large diameter wheel, the load is farther from the effort, which means less power, but a longer distance moved — which means more speed.

Steam locomotive power is also related to cylinder size and shape. A larger diameter cylinder will provide more power than a small one. A large drive wheel needs a cylinder with a longer stroke, which — all other things (such as steam volume) being equal — means a smaller cylinder diameter, which also means less power.

The size of the cylinders is dependent on the amount of steam the boiler can produce, which is directly related to the size of the firebox grid. The bigger the firebox and boiler, the heavier the locomotive is, which generally means more length, which means more wheels. Heavier locomotives are less likely to slip on the rails under heavy load, so generally the more weight the locomotive will be called upon to pull, the more drivers it will have, vs. unpowered lead and trailing axles whose purpose is simply to carry the engine’s weight. Wheel slippage isn’t as much of an issue with passenger locomotives, because passenger trains are generally shorter and lighter than freights. When a bigger passenger engine is needed, its larger boiler and firebox can be supported by more leading and trailing axles, rather than more drivers.

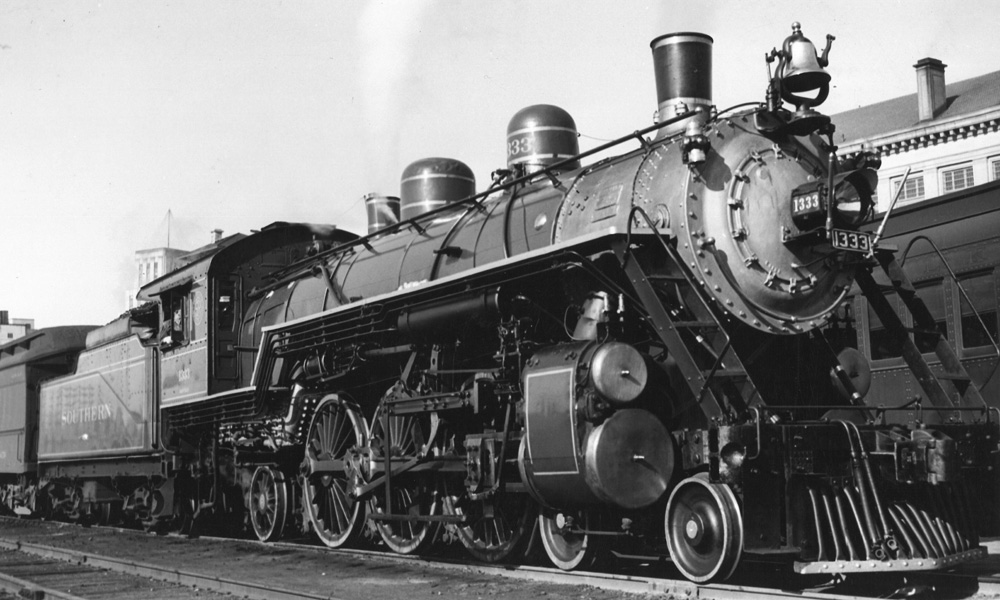

There are other factors that govern the number of drive wheels vs. leading and trailing axles, such as the fact that you can’t fit a large firebox between the drivers, so it has to be supported by a larger trailing truck. But in general, when you see a locomotive with a high number of small driver wheels vs. pilot and trailing axles, such as a 2-8-2 Mikado, 2-10-0 Decapod, or 4-6-6-4 Challenger, that’s generally a freight engine, built for pulling strength. An engine with a high proportion of pilot and trailing wheels compared to the number of drivers, like a 4-4-2 Atlantic, 4-6-2 Pacific, or 4-8-4 Northern, is usually passenger power, made for speed.

As for climbing hills, what you need there is more traction. So a railroad in mountainous territory may decide to assign what other roads would classify as freight power to its passenger trains. The trains will be slower, but they’ll get there more reliably.

If you want to dive deeper into how steam locomotives work, we’ve got a book for that — How Steam Locomotives Work, available now in the Kalmbach Hobby Store.

Send us your questions

Have a question about modeling, operation, or prototype railroads? Send it to us at AskTrains@Trains.com. Be sure to put “Ask MR” in the subject.