Railroad dome cars are a gleaming symbol of postwar passenger train status.

The streamliner era in North America bookended the World War II era in the U.S., since new streamlined passenger cars were not a priority between 1942 and 1945. Following the end of the war in the latter year, they began to appear again, with the railroads’ hope that the banner traffic experienced during the war would continue during peacetime.

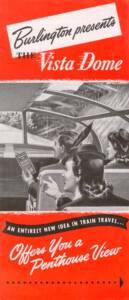

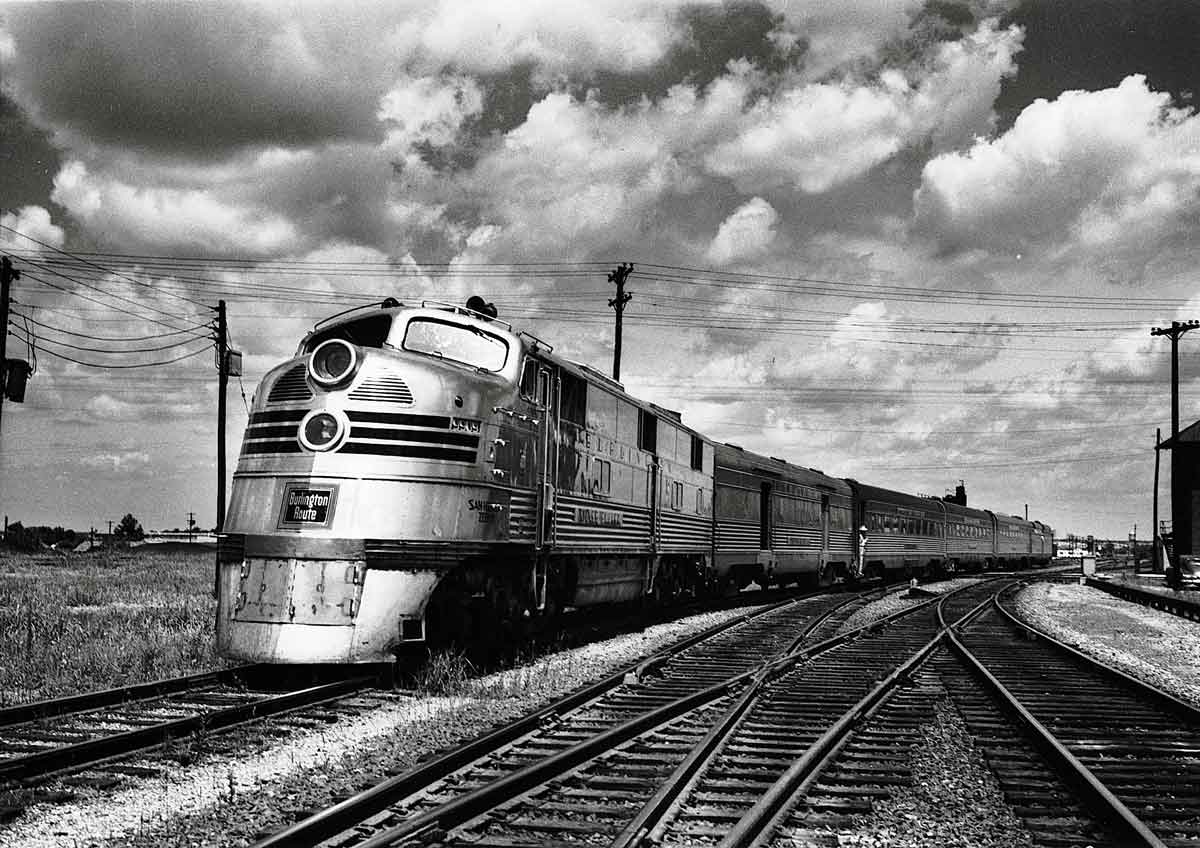

In 1945, the Chicago, Burlington & Quincy brought forth something both new and novel, in the form of the dome car, when it introduced a pair of Budd-built pre-war stainless-steel coaches with glass-topped domes (including seating for passengers) added above the cars’ previous rooflines. The “Q” then followed up in 1947 by taking delivery of its Twin Zephyrs, which plied the railroad’s route between Chicago and the Twin Cities of Minnesota via the scenic upper Mississippi River valley.

Each set of equipment made a round trip daily and typically featured four dome coaches and a dome parlor observation; only the baggage-lounge and the dining car did not feature the new innovation. In the same year, Pullman-Standard built a four-car trainset that could be described as a proof of concept/demonstrator in conjunction with General Motors; this included a chair car, dining car, sleeping car and observation car, each with a dome. Following a barnstorming tour of various points in the U.S., the Union Pacific acquired the equipment in 1949 and used it in its “pool service” with the Northern Pacific between Seattle and Portland, Ore.

In 1948 a pair of other varieties of dome equipment appeared. Passenger service proponent Robert R. Young’s Chesapeake and Ohio took delivery from Budd of its planned Chessie daytime streamliner service which included both dome observations and dome sleepers, which were to be used as private day rooms.

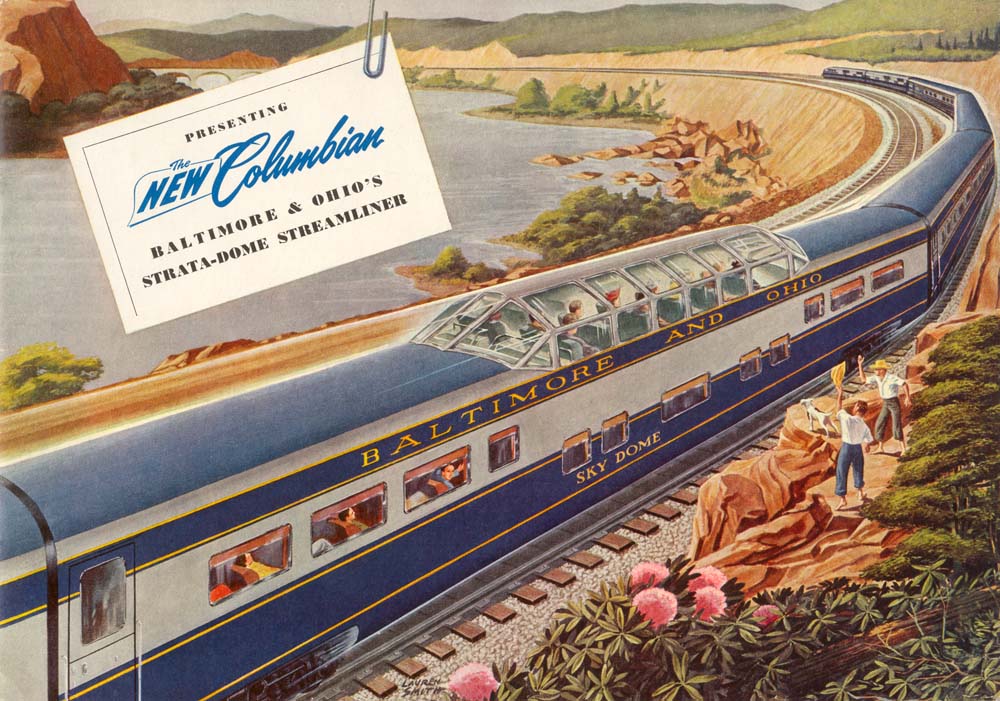

Since the Chessie never entered regular service, the sleepers were sold to the Baltimore & Ohio, which used them on its premier Capitol Limited, while the Denver & Rio Grande Western acquired the dome observations. Budd also supplied a trio of dome coaches to the Missouri Pacific for use on the Colorado Eagle between St. Louis and Denver.

The next year, 1949, the B&O took delivery of two dome coaches for use on its new all-coach Washington, D.C.-Chicago Columbian overnight streamliner. These were built by Pullman-Standard and had “low-profile” domes (as did the Chessie) due to tight clearances on this route. Interestingly, these two cars, along with eight other “regular” coaches were the only postwar lightweight coaches acquired new-from-the-manufacturer by the B&O.

The big news in 1949, however, was the delivery of the cars for the California Zephyr, utilizing a trio of railroads (Burlington; Rio Grande; Western Pacific) for this service between Chicago and the San Francisco Bay area. Each consist had five domes: three coaches, a lounge-dormitory, and a sleeper observation.

Surprisingly, in 1950, the Wabash became a dome operator with the launch of its Budd-built Blue Bird, operating a daily round trip between Chicago and St. Louis. The consist bore more than a superficial resemblance to the Twin Zephyrs, with a flat-topped baggage lounge and diner, plus a dome parlor observation and dome coaches, although only three of the latter for the Wabash version, as opposed to four on the Burlington’s trains.

Surprisingly, except for the California Zephyr, the only other dome cars that regularly ventured west of the Mississippi River at this point were the Mopac’s on the Colorado Eagle, and they didn’t get west of the Continental divide. This situation was altered by the Santa Fe’s acquisition of the Pullman-Standard dome lounges for the railroad’s Super Chief in 1950; these “Pleasure Dome” cars also contained the famous premium-service Turquoise Room dining accommodations.

However, it’s interesting to note that as of 1951, many of the trains in the west that we now look back on fondly as domeliners had yet to have this type of equipment added to their consists. 1952 featured several re-orders from roads already operating dome cars, including the Missouri Pacific for additional dome coaches, this time from Pullman-Standard; an additional CZ sleeper observation; and a dome-parlor for the Blue Bird, also from Pullman.

There was a noteworthy “new in ‘52” event on the dome front, in the form of the Milwaukee Road’s acquisition of 10 full-length “Super Domes” from Pullman-Standard. Six of these were for the road’s Olympian Hiawatha between Chicago and Seattle/Tacoma, thus introducing dome service on the “northern transcon” route.

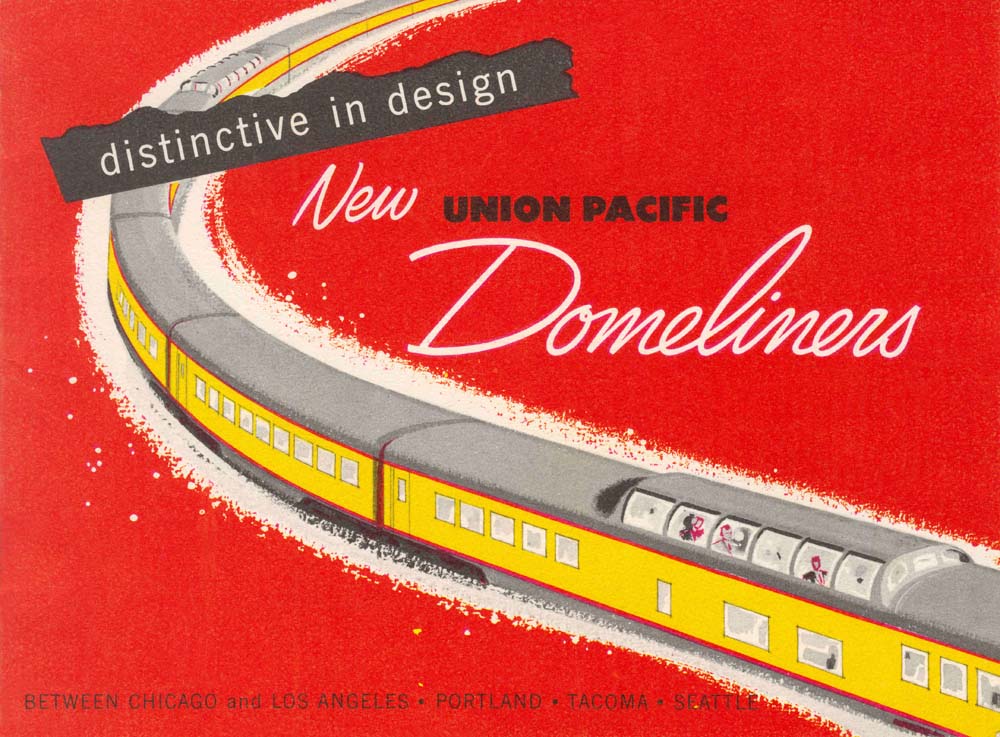

1953 featured only the addition of a pair of dome-coach/dormitory/buffet lounge cars for the Burlington’s Kansas City Zephyr. 1954 was a banner year for new dome cars, however, with the Union Pacific adding dome coaches, observation lounges and what would be the only dome diners. The Santa Fe acquired full-length dome coach/lounges in two slightly different configurations, and the Northern Pacific met the Milwaukee Road’s competition with the addition of both (regular/short) dome coaches and sleepers.

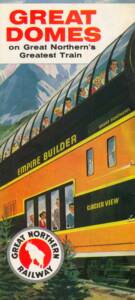

By 1955, the Great Northern had gotten the memo, and put both dome coaches and full-length dome lounges into service on the Empire Builder. In chromatic terms, certainly the Chicago-Pacific Northwest route took the prize for best-looking domeliners, with the Builder’s green/orange with yellow stripes, the NCL’s post-1956 two-tone green paint scheme devised by famed designer Raymond Lowey, as well as the Milwaukee Road’s initial maroon and orange, as well as the Milwaukee’s later adoption of UP’s Armour yellow.

Two other noteworthy events in 1955 were the Southern Pacific’s rebuilding of various early lightweight cars into semi-full length low-profile domes (to deal with clearance issues), and the large (18 trainsets) for the new Canadian transcontinental streamliner, and re-equipping of the Dominon; each set included a dome coach and a dome sleeper-observation much like those on the California Zephyr.

1956 brought the re-equipping of the Burlington’s Denver Zephyr, which added a pair of three kinds of dome cars, including buffet lounges, coach and parlor observation to the Burlington’s substantial roster of Budd dome cars. That year the same manufacturer also introduced the “Hi-level” El Capitan for the Santa Fe, which offered upper-level accommodations to the full length of the train; this arguably prefigured the later Amtrak Superliners.

Finally, to use a musical term, there was a coda for domes in 1958, when six dome coaches arrived to make the UP’s City of St. Louis a domeliner (one was owned by the Wabash). The fact that the UP was willing to invest in new, and beyond-the-ordinary equipment for a train that had no effective competition at its namesake city this late in the postwar passenger service game (the so-called Hosmer Report, with its famous “no passenger trains by 1970” prediction appeared in the same year) suggests that not all rail management fit the “heartless robber baron” description.

Another correction for 1953. The Kansas City Zephyr order also had a pair of dome-parlor-observation cars – the first flat-end observations acquired by the CB&Q.

One small correction: the North Coast Limited’s two-tone green paint scheme was designed by Raymond Loewy by March of 1953 and repainting of the rolling stock was complete by 1955.

The statement that Union Pacific had the only dome diners is incorrect. The Santa Fe “Pleasure Domes” diner-lounges included the “Turquoise Room” seating 12.

By dome diners it is meant that the dining room is in the actual dome section of the car. UP was the only road to have this type of diner in the time before Amtrak.

I remember seeing a dome coach on Amtrak’s CHI-MIA ‘Floridian’ in ’73-’75. It had a low profile, probably ex B&O. That was a nice ride Miami to Waycross: dinner in the diner soon after leaving Miami, then enjoying the ride in the dome straight up the ‘S’ line to JAX, and then on toward Waycross.(where I got off to mark up on the extra board at SCL the next day). The N&W ‘Powhatan Arrow’ had a dome coach, Cincinnatti-Norfolk in the mid-late ’60s. Probably ex Wabash?

I rode the City of Los Angeles from Pomona, CA to North Platte, NE several times in the 1960’s.

This train had two Dome Liners, one strictly for observation, and the second was a dining car.

My mother gave me money for food during the trip with the stipulation that I could only eat in the dome diner once. It cost more to dine in the dome diner.

My best memories of those trips was the funny stories the staff told me after the diner closed.

Considering the “tariffs” that the administration has put into effect on foreign steel and the associated countries that are now producing Amtrak and all other forms of transit equipment, maybe the time has come for a resurgence in building this equipment in the USA.

I love domes. Twice I’ve been inside of dome car Challenger first time I rode it second time it was on display over at Ogden but it is great to be inside that thing.