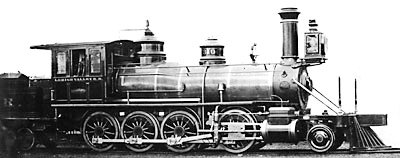

The first 2-8-0 was delivered to the Lehigh Valley in 1866 for operation over the mountain grades of the railroad’s Mount Carmel Branch in Pennsylvania. The locomotive was built by Baldwin, but had been designed by the master mechanic of one of Lehigh Valley’s predecessor railroads, the Lehigh & Mahanoy.

The new design incorporated a self-centering radial engine truck that was equalized with the driving wheels to form a three-point suspension system. As a result, the 2-8-0 was a stable riding engine – much more so than the early 0-8-0s used in road service – and this made it capable of greater speeds. With eight coupled drivers, the 2-8-0 also had excellent adhesion.

The engine quickly proved itself on the Lehigh Valley and the railroad ordered fourteen copies. The first LV locomotive was named Consolidation – the same year it was introduced the Lehigh Valley completed a strategic merger with the Lehigh & Mahanoy – and this name was later applied to all 2-8-0 locomotives.

The Consolidation turned out to be one of the all-time great locomotive designs. It could ably handle mountain grades, and a decade after its introduction it became the standard heavy freight engine.

Mountain railroads such as the Erie, Pennsylvania, and Baltimore & Ohio began replacing 4-4-0s with 2-8-0s in freight service. Compared to a 4-4-0, the 2-8-0 could pull trains that were twice as heavy at less cost. The widespread use of air brakes in the 1880s prompted railroads to run heavier trains, which the 2-8-0 proved more than capable of handling, further solidifying its position as America’s preeminent freight locomotive.

Consolidations were built continuously into the 1920s and received the latest advances in steam locomotive technology, such as superheaters, stokers, feedwater heaters, piston valves, outside radial valve gear, and more. Driving wheel size increased steadily from 51 inches to 63 inches, which increased the engine’s speed potential.

The size of the 2-8-0 grew from the small Lehigh Valley engines to those built by Baldwin for the Western Maryland and Reading, which had axle loadings in excess of 35 tons and weighed more than 280,000 lbs.

By the time the last 2-8-0s were delivered in the 1940s, more than 33,000 had been delivered – more than any other type of steam locomotive built in the U.S.

Competition for the 2-8-0 came principally from the 2-8-2. By 1920 it was no longer enough to just pull a big train – a locomotive also had to move it fast. While the 2-8-0 had adequate adhesion, it did not have the raw horsepower needed to lug heavy trains at anything other than drag freight speeds. The 2-8-0’s shallow firebox was located above the drivers and, as such, it did not have sufficient furnace volume to support the high rates of combustion needed to generate high horsepower.

The solution came in the form of the 2-8-2, which had a deep firebox placed behind the driving wheels, supported by a two-wheel trailer truck. While the 2-8-2 had no more adhesion than a large 2-8-0, the 2-8-2’s big firebox gave it the ability to evaporate water at a substantially higher rate. And this is what made the difference.

On most railroads – but not all – the 2-8-2 and other modern designs replaced Consolidations in main-line freight service. Older engines met the torch, while others gravitated to branch lines, local freights, or yard duty. Consolidations also became popular short line engines.

It was the diesel that ultimately vanquished the 2-8-0 from the rails. Many Consolidations remained active until the very end of steam.