Lucius Beebe was a major figure in railroad literature and photography for nearly three decades, but contemporary readers might be amazed at just how far his reputation spread beyond railroading. He could have starred in the old TV show, “Lifestyles of the Rich and Famous.”

Beebe was born Dec. 9, 1902, in Wakefield, Mass. His father, Junius Beebe, was successful in several businesses, including leather, gas, and banking. Beebe grew up on the family’s 140-acre Beebe Farm, attended exclusive preparatory schools, and entered Yale in 1923. A congenital prankster and troublemaker, he managed to get himself kicked out of the university, then went down the road to Harvard, which also suspended him briefly, but he returned to graduate in 1926.

Beebe was drawn to a journalism career and worked for several papers in Boston before joining the New York Herald Tribune in 1929 at age 27. In 1933, he began writing a column called “This New York,” chronicling Manhattan’s high society. He made few bones about objectivity; he was as deeply involved in café society as the luminaries he wrote about. A 1939 appearance on the cover of Life magazine — in top hat and tails — underscored his penchant for making various “best dressed” lists. He remained on the Herald-Tribune staff for 21 years.

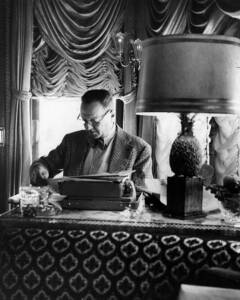

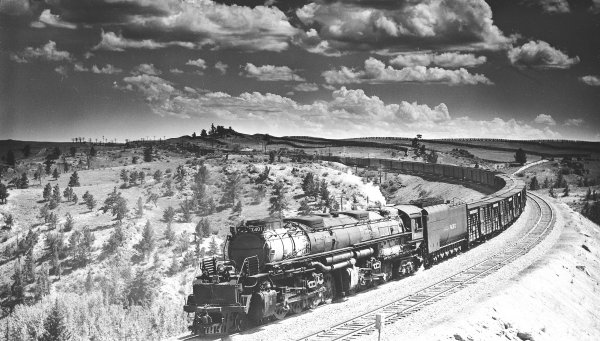

Even as he threw himself into the social whirl, Beebe was consumed by railroading and train travel and became a regular customer on New York Central’s Twentieth Century Limited, among other trains. Beebe also became a skilled photographer. Armed with a ponderous Speed Graphic camera, he perfected a style of three-quarter-angle action photography showcased in his groundbreaking books for Appleton-Century, beginning with High Iron (1938), and continuing through Highliners (1940), Trains in Transition (1941), and Highball (1945).

In 1950, Beebe and his partner/collaborator, Charles M. Clegg, moved to Virginia City, Nev., where they embarked on an astonishingly productive run of books for Berkeley, Calif.-based Howell-North, including Mixed Train Daily (1947), The Age of Steam (1957), Mansions on Rails (1959), and Twentieth Century Limited (1962). More than just a writer, Beebe also brought his considerable photo editing skills to bear on these books and, along with David P. Morgan, helped bring the work of Richard Steinheimer, Philip R. Hastings, Robert Hale, and Jim Shaughnessy to a wider audience.

As part of his migration west, Beebe in 1952 purchased Virginia City’s dormant Territorial Enterprise newspaper and revived it. By 1954, the weekly boasted a record circulation. He also continued to write for a number of national magazines — among them Gourmet, Esquire, Holiday, and Playboy — and in 1960 began writing the column “This Wild West” for the San Francisco Chronicle.

Beebe and Clegg continued to live the high life, especially aboard their two ostentatious private railroad cars, Virginia City and Gold Coast. Newspapers of the era were fascinated by what today would be called their “retro” lifestyle, and they appeared frequently in feature photos taken in the rococo surroundings of the Gold Coast’s observation salon. Usually at their side would be T-Bone Towser, their omnipresent St. Bernard. (Today the Gold Coast is exhibited at the California State Railroad Museum.)

Despite failing health, Lucius Beebe kept up a steady production of books into the 1960s. When he died of a heart attack on Feb. 4, 1966, at home in Hillsborough, Calif., he was working on the two-volume valedictory, The Trains We Rode.

Five must-read books by Lucious Beebe

Lucius Beebe was prolific; he wrote 40 books, most of them grandiose anthologies featuring his inimitable commentary and loaded with photographs from a host of big-name shooters (notably his partner, Charles Clegg). Although he occasionally produced books for New York publishers, his longtime collaborator was Howell-North Books. Of the Beebe canon, five are indispensable:

High Iron (Appleton-Century, 1938): The book that started it all, a hardbound showcase of classic three-quarter “wedge” action shots of trains, all of them behind steam locomotives going full-bore, usually rods-down and nearly jumping off the page.

Mixed Train Daily (Howell-North, 1947): A masterpiece, probably Beebe’s most fully realized book. Beebe adored short lines, a passion that comes through in this panoramic tribute to the famous (Virginia & Truckee, Rio Grande Southern) and the obscure (Prescott & Northwestern, Sylvania Central). Much of the prose is sheer poetry.

Hear the Train Blow (E.P. Dutton & Co. Inc., 1952): Beebe gathered up the whole century-plus history of American railroading with this overly ambitious but rollicking 416-page blockbuster. Best chapter: “The Grim Reaper,” about 19th century train wrecks.

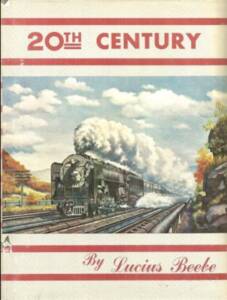

Twentieth Century Limited (Howell-North, 1962): This might have been Beebe’s favorite book, given his oft-professed love for New York Central’s legendary Chicago-New York extra-fare train. Beebe had his share of martinis on Nos. 25 and 26.

The Trains We Rode, Volumes I and II (Howell-North, 1965): Much of this majestic work was finished by Clegg after Beebe’s death in 1965, but the master’s fingerprints manifest themselves all over its pages. A dazzling curtain call, it amply supports the author’s thesis that the great passenger trains were, in essence, an extension of the world’s best hotels.

Beebe contributed mightily to my lifelong appreciation of language and evocative writing. One favorite – Beebe eschewed airplanes and aviation. I framed this early quote – “I think the circumstance that only fourteen percent of living Americans have ever been close enough to the Wright Brother’s folly to vomit into a plastic container, which has always seemed to me the perfect symbol of air transport, is the most heartening augury for the continued sanity of the Republic since the repeal of prohibition.”

Might have noted that Beebe and Clegg were a gay couple and fairly open about it. Quite bold for their time.

“When Beauty Rode the Rails” was the lone railroad book in our local library circa 1965.

At age eight I’d been interested in trains until borrowing the above named book.

Ergo Beebe dramatically improved my reading skills, vocabulary and fostering a lifelong love of all things railroad.

Historically accurate? Not by a mile —even at eight I could tell that Beebe loved a good yarn.

But his prose as well as his and Clegg’s visual art has provided me with a life filled with a love of language and trains.

Even though our worlds are/were poles apart, I’ll always be grateful that that first book in my local library!

Note about the above comment:

Predictive text is my worst enema …