In the 1920s, as Argentina’s economy boomed and its railway system expanded, toy trains began to capture the imaginations of children and adults.

Because British investors and engineers played a key role in Argentina’s railroad development, it made sense that the first toy trains came from European manufacturers like Hornby. It was a simple matter for Hornby to add a bit of paint or special lettering and begin selling “Argentine” trains to compete with toys from other German, English, and American manufacturers.

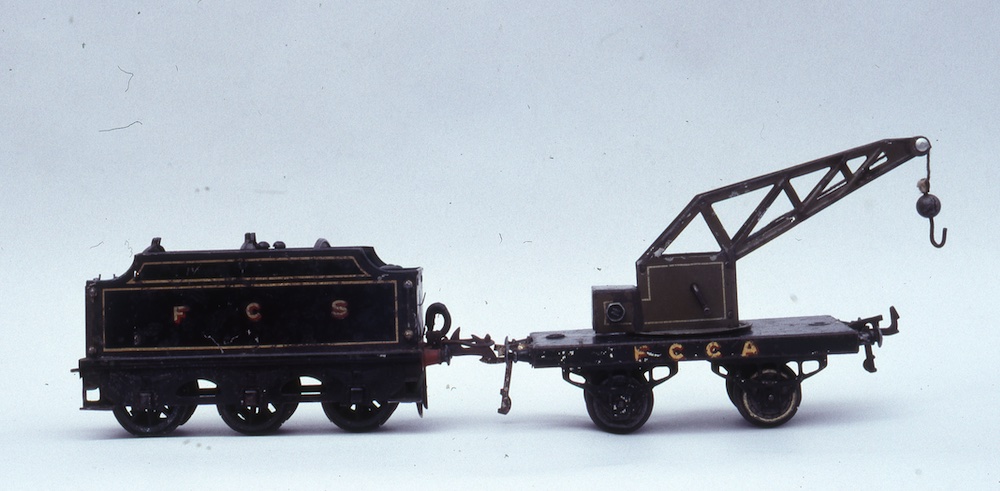

Many Homby trains during this period (from 1925 to approximately 1939) were lettered for the four main Argentine railways: Ferrocarril Central de Argentina (FCCA), Ferrocarril del Sud (FCS), Ferrocarril del Oeste (FCO), and Buenos Aires al Pacifico (BAP, possibly the rarest).

In addition to the railroad initials, most cars also had a bottom decal advising “Fabrique en Angleterra,” indicating production for export. A limited number of cars also had an English “Hornby Series” label.

Some cars of the period came without any road name but with English inscriptions (such as “Wine Wagon). All of the passenger sets exported to Argentina carried the full British regalia. For freight equipment, there were two styles of lettering, one with large painted initials and the other with smaller (and more elegant) letters.

Around 1939, a local toy company named C. Matarazzo, S.A. started producing a line of clockwork O gauge trains. Matarazzo initially produced the lowest-cost toy trains possible, using the lightest weight tin for its cars, locomotive, and tight-radius track. Matarazzo had obviously studied the American market, as their box shows graphics similar to Lionel’s M-10000 streamliner heading under a Hell Gate Bridge, despite having no connection to the inexpensive toy train found inside.

A look at a catalog from the early 1950s shows a small toy train line with a few accessories. Production consisted of a single clockwork locomotive, with tender and one style of passenger car. Optionally or as a set, this locomotive was available with three styles of freight cars: a boxcar, cattle car, and a tank car (lettered for YPF, the Argentine oil company).

Consumers could add a tin tunnel and a small station (named Palermo) with five lead figures. The catalog also lists a large, well-made clockwork two-car streamlined passenger train set, with wide-radius curved track. These cars were lettered for “Constitucion” (a Buenos Aires station) and resembled a streamlined train that operated south to a popular resort in the early 50s.

Sometime in the mid 1950s, Matarazzo changed its lithography to reflect railway name changes that occurred after the 1948 government purchase of the railways. The same engine and cars continued but the colors became brighter and the tender was lettered for the General Roca Railway (FGR). The one surviving example of a modem passenger car improbably displays a single window with an artist’s vision of the dining car interior, equipped with just one table!

Additional buildings were added to the line, which included a “Cabina de Senal” equipped with a semaphore signal (sold separately from the building). The Cabina received different lithography and became a suburban station after losing its signal.

Other known changes included the electrification, three rail track, and a transformer. It is likely the freight cars received new lithography and it is possible that other sets were developed. They did produce a bizarre looking monorail that looked like a streamlined diesel locomotive (an Alco PA). This elaborately lithographed clockwork engine pulls itself along a string hanging between tin girders. No add-on cars were ever produced.

Matarazzo marked its products with a stylized “M,” the company name, and the phrase “Industria Argentina.”

It is thought that Elektro, a little-known manufacturer that started making toy trains in the 1930s, made the only set in two different colors before ending business sometime in the 1960s. This brought an end to O gauge production in Argentina.

Note: All information is based upon one undated Matarazzo catalog (thought to be early 1950s) and reports from local citizens, except for Hornby, which has been well documented in books.

Great to see some toy/model trains from other than USA mentioned in a Classic Toy Trains article. There were quite a few interesting models made in other countries.