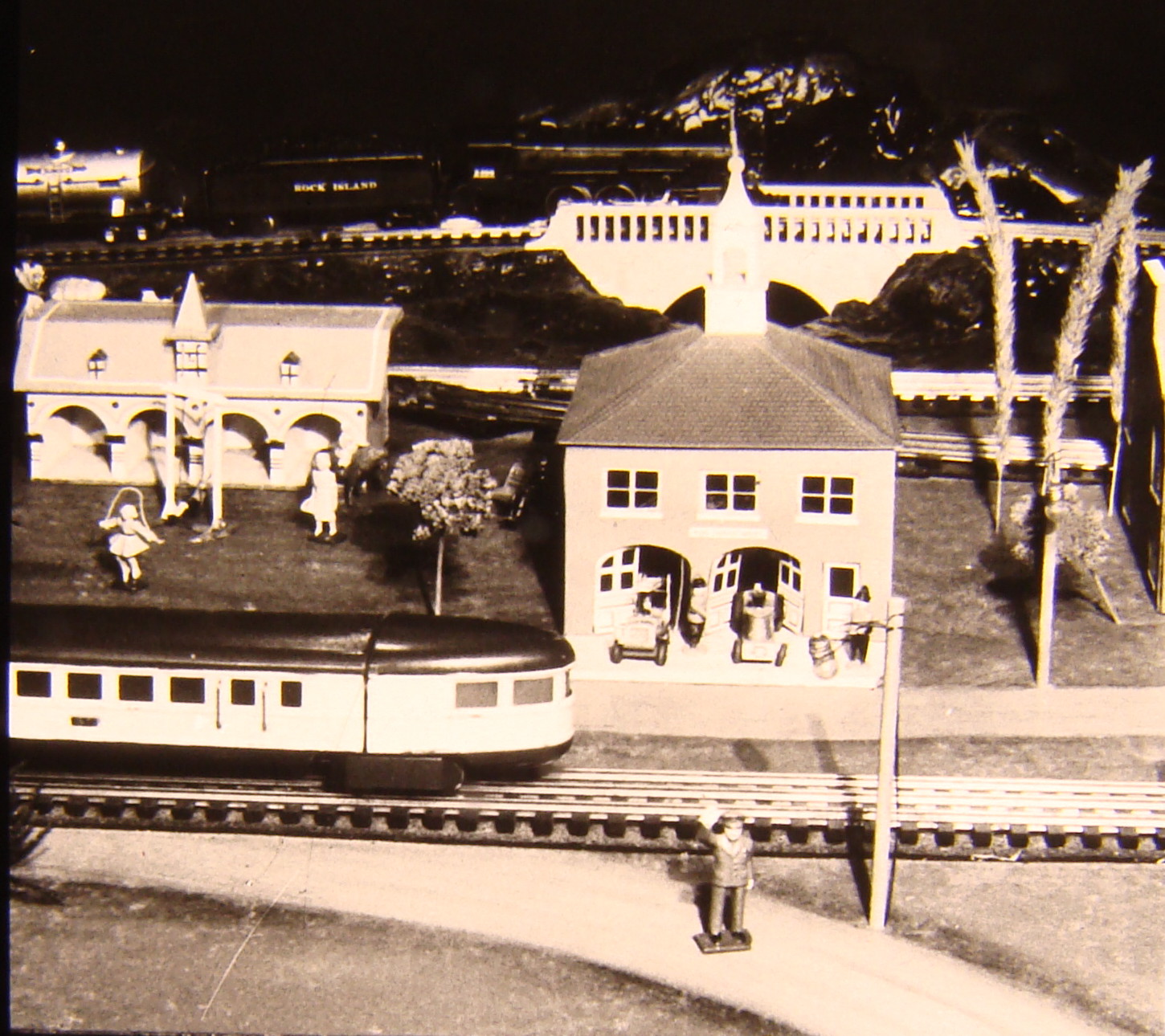

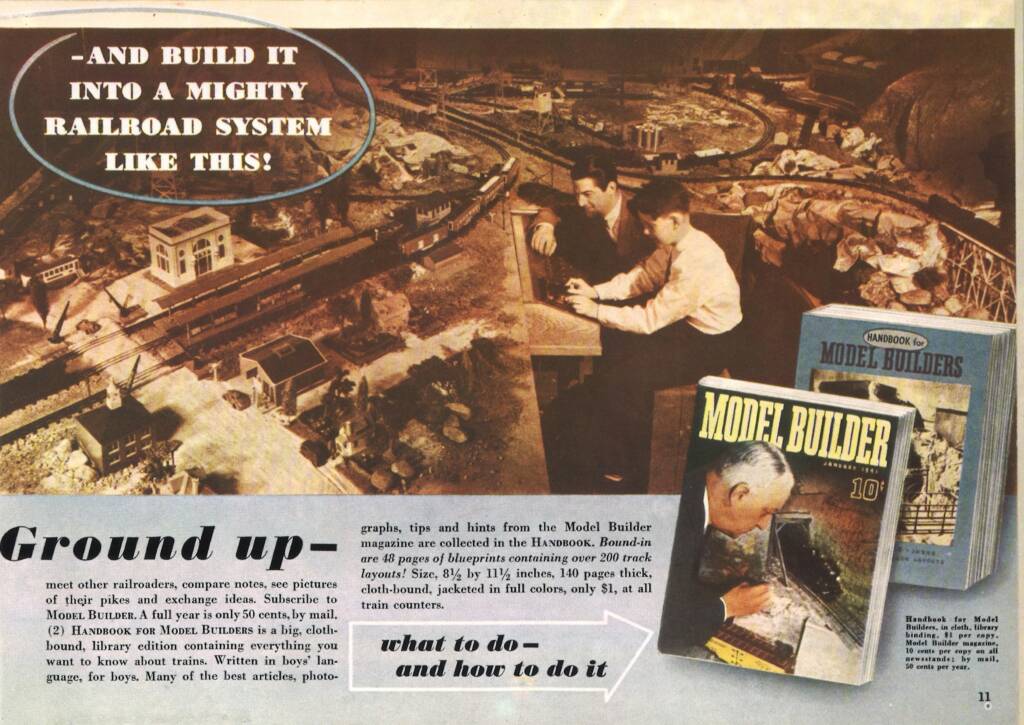

Talk about inspiring dreams of greatness! Sepia-tone photographs sprinkled about in the opening pages of Lionel’s consumer catalog for 1940 couldn’t have done a better job of persuading kids and their fathers to buy an electric train and build a model railroad. Especially convincing was the picture on page 11, the companion to one on the opposite page that showed a boy and his dad starting construction.

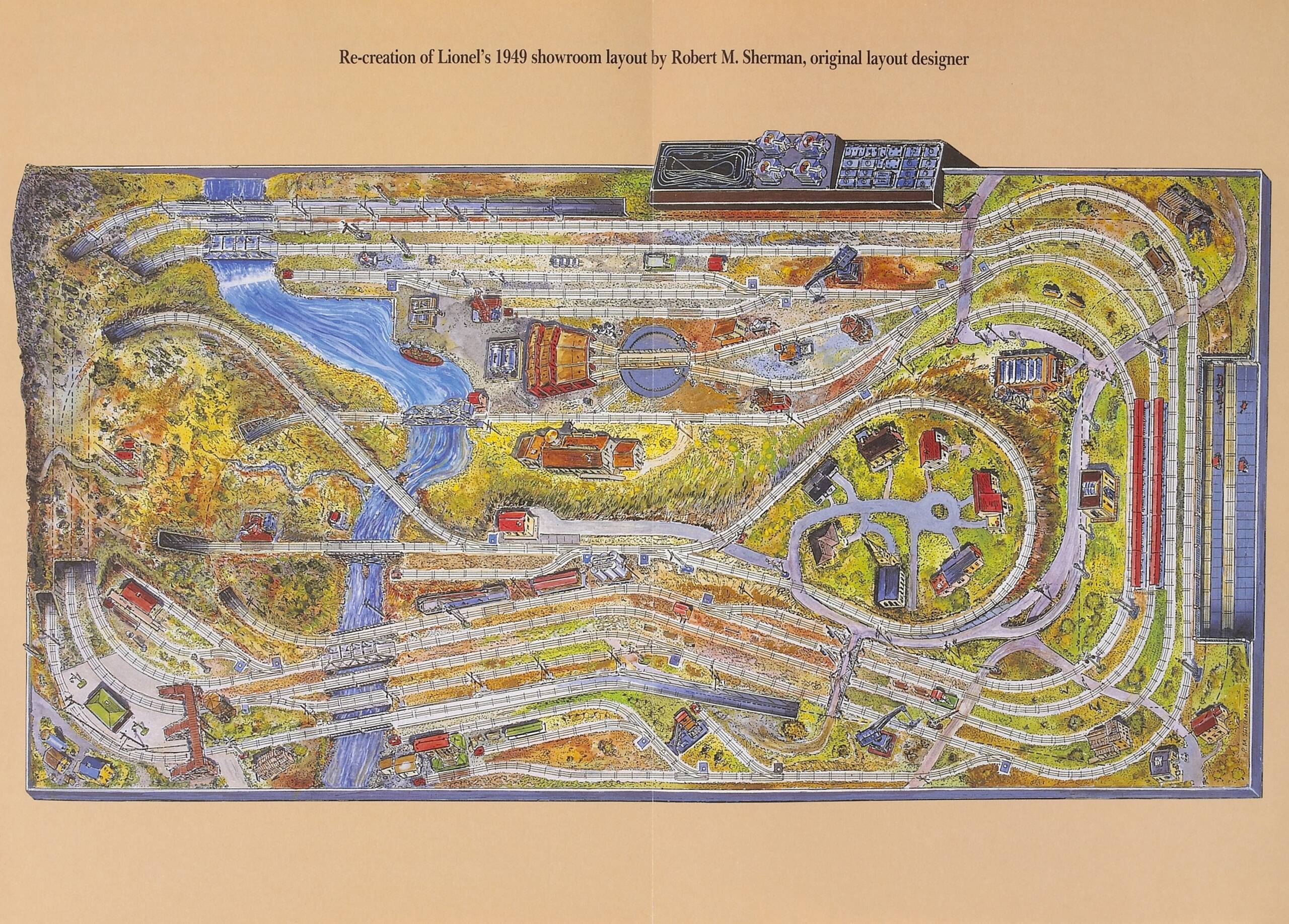

One glance at the sprawling O gauge layout (the text referred to it as “a mighty railroad system”) was enough to ignite a passion to plan and build in any hobbyist. The rows of No. 156 Station Platforms adjacent to the No. 115 Station looked so realistic, and the scattered freight loaders on the right side guaranteed fun. The layout captured the glory of Lionel amid the company’s 40th anniversary.

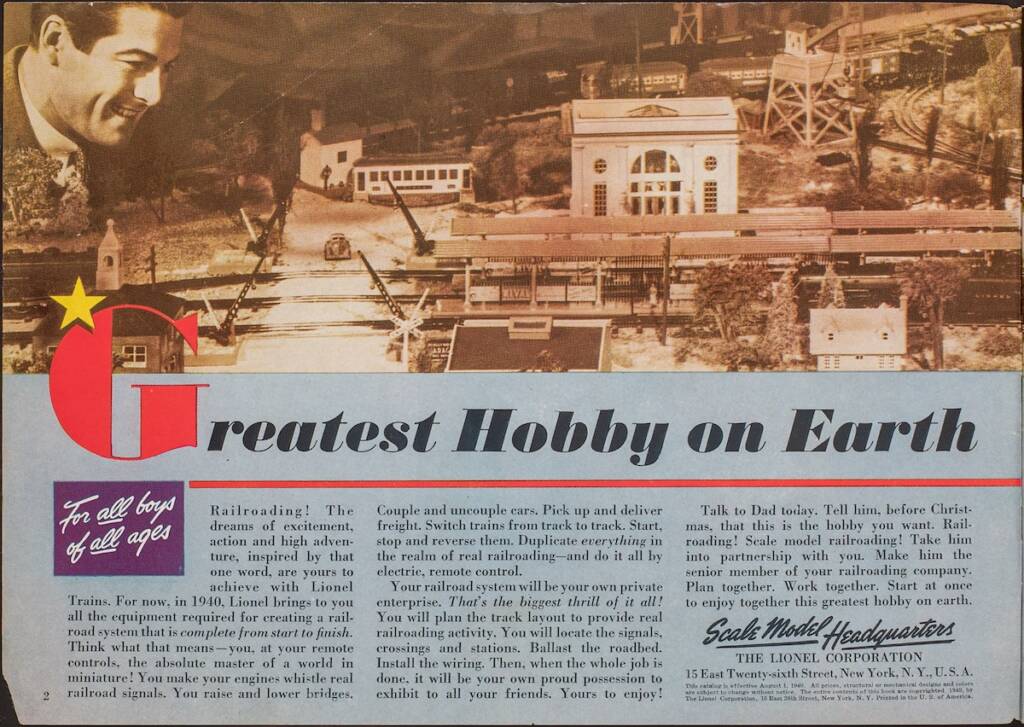

You might think the individuals in the Advertising Department who were in charge of developing the consumer catalog would have been eager to promote the three-rail empire. They certainly emphasized its importance, reproducing more photos, notably the detailed shots on pages 2 and 3 of the catalog used to proclaim scale model railroading by Lionel to be the “Greatest Hobby on Earth.”

Yet to the frustration and disappointment of Lionel enthusiasts in 1940 and ever since, the magnificent layout was never identified. Let’s make a valiant effort to learn about it while trying to relate it to the World’s Fair held in 1939-40.

Very mysterious

The closeup shot on the inside front cover of the massive 64-page catalog truly justified the declaration that readers were engaged in the “Greatest Hobby on Earth.” Who wouldn’t want to enlist in the corps of Lionel fans after seeing it?

Anyone capable of appreciating the landscaped scenes hosting lines of three-rail track surrounded by trackside items and other impressive accessories quickly asks the most elementary question: Where was this incredible layout?

About all we can conclude with assurance is when the railroad was built. A few items on it were making their debut in 1940, so that had to be the year the layout was assembled. The examples of the Nos. 156 Station Platform and 165 Triple-Action Magnetic Crane evidently removed doubts about when it was built.

Anything else about the immense and complex display remained shrouded in mystery. Let me see what I can do to shed a little light on the classic railroad.

Earlier displays

To start, however, we need to put the images from Lionel’s 1940 catalog in context. And it’s not a pleasant one. Few photos of displays of any kind from the first four decades of the 20th century exist. Think of the outstanding layouts, both small and large, that must have been built during the prewar period for Ives, Lionel, and other brands of toy trains. Virtually all records and pictures of the displays at trade shows, department stores, and public expositions have vanished.

Luckily for us, “virtually all” doesn’t mean every single one of them! A smattering of black-and-white pictures showing toy trains in such settings have survived. Publications from Lionel and its competitors as well as toy industry periodicals (primarily, Playthings and Toys & Novelties) do have photographs.

Unfortunately, nearly all of those vintage images offer only views of static presentations of sets, engines, stations, and signals in store windows or arranged on shelves or counters. Photos of actual operating displays seldom were shown.

The best source of pictures of O gauge railroads that operated are Lionel catalogs. The ones aimed at consumers often featured photographs of layouts, typically placed next to artwork and descriptions of the latest outfits and trackside accessories. To state it more accurately, they featured photos of one layout — namely the display filling the middle area of the Lionel showroom in New York.

Research proved that pictures of the display having four concentric loops of O gauge track were printed in the 1936 and ’37 catalogs. Photos of the T-Rail Layout completed in 1938 became the central draw in the 1938 and ’39 catalogs.

The only opportunity to see toy trains in action from the prewar era is to head to the movies, where they occasionally served as props. Comedian Buster Keaton launched that wonderful trend in 1922 with his silent short, The Electric House. American Flyer and Lionel sets made regular appearances in motion pictures released during the following decade. Audiences delighted in being able to watch locomotives pull freight and passenger cars on layouts varying in size.

World’s Fairs

The absence of vintage photographs of operating displays from the prewar era doesn’t mean few such displays were being constructed. To the contrary. As the financial impact of the Great Depression lessened during the second half of the 1930s, interest in miniature trains of different scales and gauges increased. Marketers searched for arenas in which to promote the little engines, cars, and ancillary items. International trade and cultural fairs met their needs perfectly.

A noteworthy example occurred in 1933 and 1934, when Chicago hosted “A Century of Progress” International Exposition. The American Flyer Manufacturing Corp., whose plant and headquarters were located in that city, made sure to display its sets and other wares in a prominent spot at the big fair.

Just a few years later, when New York City hosted an even larger event, Lionel made certain to be there. According to an article in the November 1939 issue of Lionel Lines (an inhouse publication for employees), a group of foremen and supervisors from the company’s factory had spent a day on the fairgrounds.

First Lionel exhibit

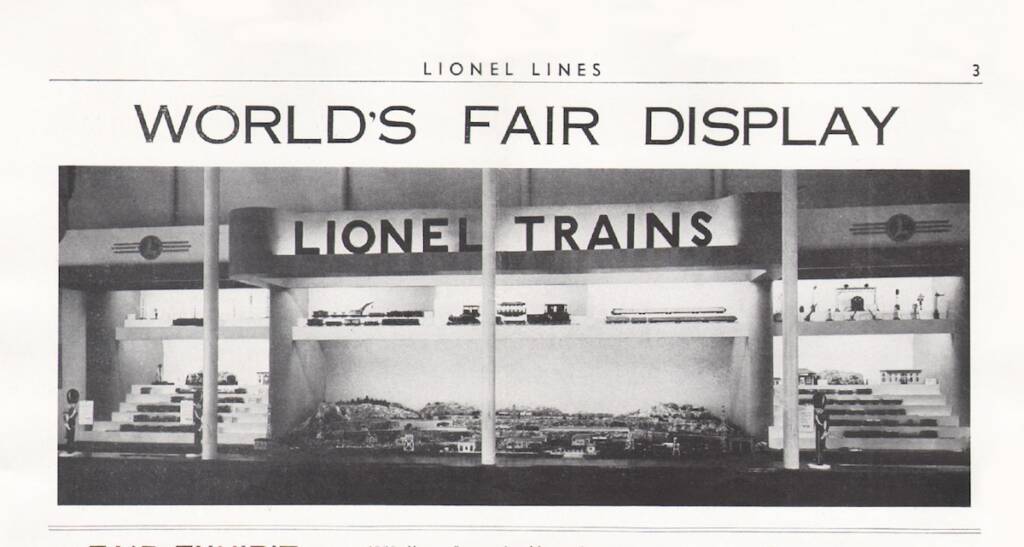

The Lionel exhibit was at the top of the men’s itinerary. A picture printed in the June 1939 issue of Lionel Lines, along with a brief article, showed the 10 x 40-foot display. The unidentified author of the item noted that Lionel’s exhibit was housed in the R.H. Macy’s Building, which was located in the Children’s World Section. The latter was, in turn, a part of the Amusement Area at the fair.

What Lionel had provided consisted of three sections. On the right and left sides were static displays of new and vintage outfits, locomotives, and accessories arranged on ascending steps. Over them were shelves filled with premier pieces.

A 7 x 20-foot O gauge layout filled the middle of the exhibit. As described in Lionel Lines, the operating display featured “a scenic diorama embodying topographical features of mountains, tunnels, waterfalls, also super-highways, bridges, and residential districts.” Four long trains could be run simultaneously.

Despite the shortcomings of the photo’s composition and clarity, enough can be discerned to prove this layout was not the model railroad shown in the consumer catalog for 1940. The dimensions and accessories missed the mark.

Bigger in 1940

Organizers of the New York World’s Fair, cognizant of problems that had hurt attendance in 1939, revamped the exposition over the following winter. The international event reopened early the next year with additional exhibits, along with some that had been updated. Among the changes was the opening of the Hall of Inventions. It took over where the Distilled Spirits exhibit had been.

According to an account published in the August 1940 issue of Playthings (a periodical aimed at members of the toy industry), Lionel had been invited to join the firms in the Hall of Inventions. That facility paid tribute to “feats of ingenuity from the mechanized age.” Specifically, the preeminent manufacturer of toy trains in America “was honored with a ‘center-stage’ revolving display spotlighting the numerous innovations born in the Lionel shops.”

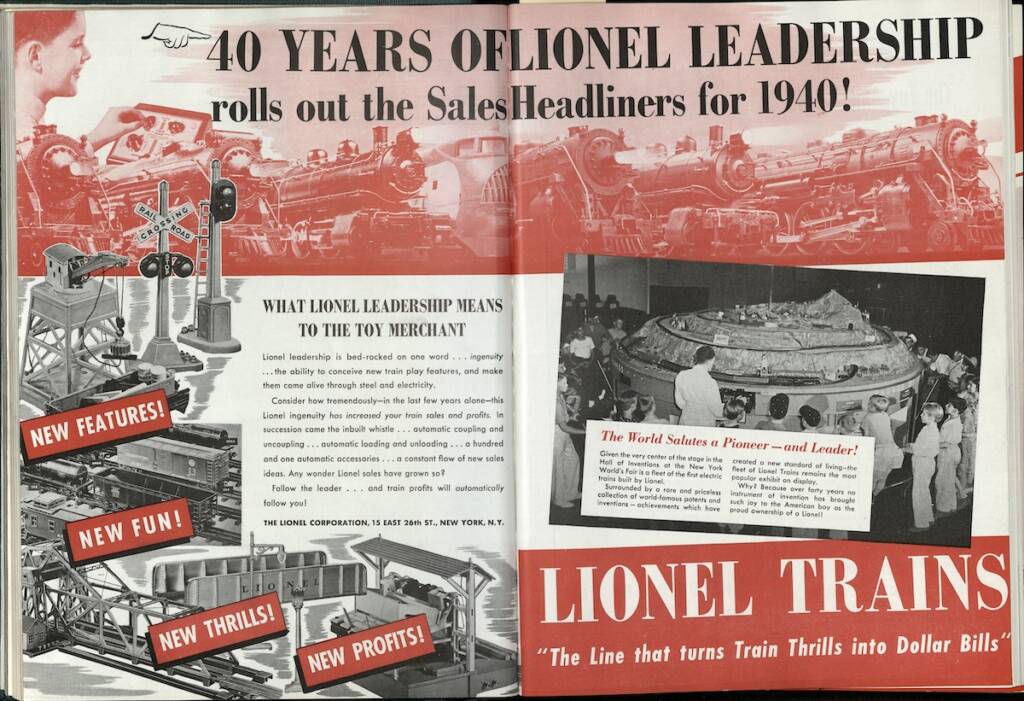

The same article in Playthings contained a black-and-white picture of the Lionel display. Elsewhere in the issue, that photograph appeared in a two-page advertisement that heralded “40 Years of Lionel Leadership.”

The huge operating display consisted of a mountain boasting three independent levels of track plus numerous structures and accessories. The trains running before crowds of thrilled fairgoers presented the impressive variety of engineering innovations Lionel had introduced in recent years.

Both the short article and the ad placed by Lionel listed the steps ahead: an onboard locomotive whistle, automatic coupling and uncoupling, electrically actuated loading and unloading cars, remote-control reversing, non-derailing switches, and “a hundred and one automatic accessories.”

Any answers?

After studying the advertisement and the article in Playthings — and feeling disappointment that the same photograph was used to illustrate both of them — I wondered whether the layout shown in the Lionel consumer catalog for 1940 might be the one erected at the New York World’s Fair. The rugged and drab scenery seemed similar, and the accessories I spied were identical. But the flat nature of the layout in the catalog images, not to mention all the trees and big rocks noticeable there, definitely set it apart.

Consequently, I tend to doubt that Lionel photographed scenes on its layout at the New York World’s Fair in 1940 for the catalog put together in that year. My hopes for solving the mystery ended up badly deflated.

Where to go next?

Adding to my frustration was realizing that, to the very best of my knowledge, the layout in the 1940 catalog didn’t remind me of any of the O gauge railroads I knew had been constructed in the Lionel showroom in New York City. The mysterious and enormous layout had a unique look.

Nor did it bring to mind any of the private or club three-rail layouts shown in Lionel’s catalogs from the late prewar era. I doubted as well that anything like it had been pictured in Model Builder, the publication Lionel put out to promote its products as well as the hobby of model railroading.

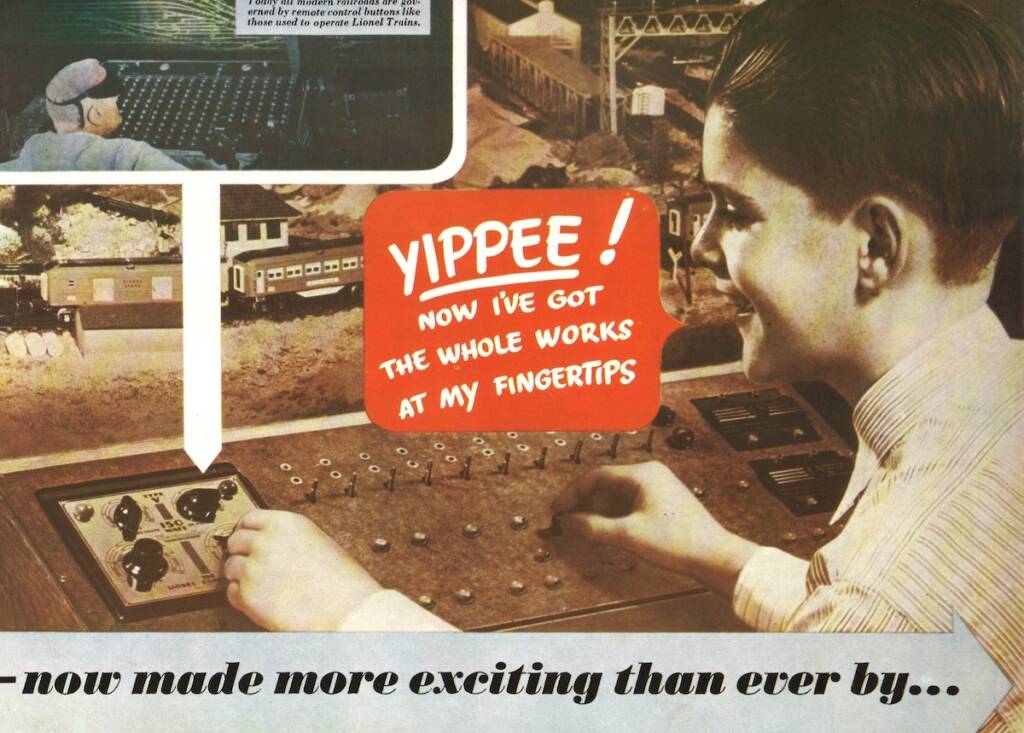

One glimmer of hope appeared after a conversation with Lionel historian Joe Mania. He pointed out similarities between the elaborate control panel shown in a photograph of the layout in the catalog and one that was illustrated in Handbook for Model Builders: Fun and Facts for the Amateur Model Railroader, which was published by Lionel in 1940.

What seemed to be black-and-white photos and not drawings of two quite sophisticated control panels appeared on pages 165 and 166 of the handbook. Since Advertising Manager Archer St. John compiled it with articles previously published in Model Builder, Joe hoped a more thorough search of Lionel’s hobby magazine might yield clues about the panel and whether it might somehow be connected with the mysterious 1940 layout.

Maybe so. Until then — or the day when additional documents or photographs of the layout surface — all we can do is believe its identity and location will miraculously be known. Then we should be able to finally pay our respects to the people or the organization that built this great layout.

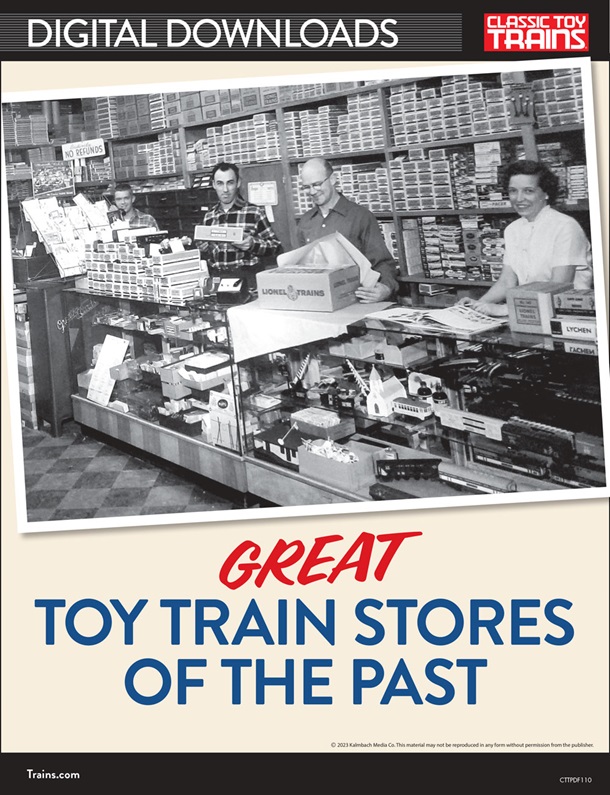

Like this article? Read more stories like this one in our special issue, Display Layouts & Showrooms.