Note: This article originally appeared in the September 2000 issue of Classic Toy Trains. In celebration of Lionel’s 125th anniversary this year, we’re sharing it online.

The Lion has just entered the big-top for his first show. He has plenty of fight, although/ he’s no longer a sleek cub. His tail is a bit frayed and his whiskers are slightly bent. But in the eyes of many, he’s still king, the star attraction, the one against whom all newcomers must ultimately measure themselves.

And that has been the case for much of the 20th century. From roughly 1920 on, Lionel has been a star, perhaps the main attraction, in the toy train circus. Lionel earned its place by overtaking older American and European rivals and fending off a horde of younger foes. Even now, no matter how enthusiastic operators might feel about new O gauge manufacturers, all comparisons center on Lionel.

Every collector can identify the strongest of the challengers, notably Ives, Gilbert, and MTH. But how about Carlisle & Finch? Or Kusan? As we celebrate Lionel’s centennial, it’s time to pay tribute to various competitors. The challenges they posed motivated Lionel to improve its trains and better its marketing to retain its toy train crown.

Old World beasts

Lionel pounced onto a scene a century ago that already was occupied by lines of electric and clockwork trains made by American and European companies. You may not be familiar with all of them, but rest assured that before too many years passed they came to know the lion. If they had spoken with candor, most would have admitted that they weren’t happy to have the growing cub nipping at their heels.

At the start of the 20th century the largest and most powerful beasts in the toy train kingdom primarily lived across the Atlantic Ocean. Märklin, Bing, Georges Carette, Schoenner, and Issmayer were all well-established German toy firms producing large live-steam trains for Continental markets and mainly smaller, inexpensive work trains for America.

The German locomotives and cars, known for attractive lithographed features, sold well despite typically being modeled after European prototypes. They were made of stamped tinplated steel, and most ran on No. 1 gauge track (1 3/4 inches between the rails). Eventually, to broaden the appeal of these trains, manufacturers “Americanized” them, modifying smokestacks and adding cowcatchers to locomotives, and decorating boxcars and passenger firms for American railroads. Making toy trains that looked more like what children saw every day was a strategy the lion would use later to revise what they were making for its German rivals.

Domestic tigers

American-made toy trains also caught the attention of youngsters at the start of the 20th century.

Producing electric trains was a logical progression for Carlisle & Finch Co. Established in 1893 by Morton Carlisle Clearly, and Robert Finch, the Cincinnati firm intended to produce “electrical novelties,” appliances, motors, military items, searchlights, and toys, but quickly became the leader in the toy train field.

Carlisle & Finch offered an electrically powered trolley in 1896. A year later, Carlisle & Finch expanded its line with a two-rail mining train, followed in 1899 by a steam-profile locomotive and tender as well as small baggage and passenger coaches, a gondola, and a boxcar. Many of these early trains were decorated using paper lithographed labels.

Electric trains proved enormously successful for Carlisle & Finch in the late 1890s and early 1900s, and the company stood tall as the largest manufacturer of such items. The young lion couldn’t miss the shadow cast by Carlisle & Finch.

As Carlisle & Finch grew, so did the Ives Manufacturing Corp., a mechanical toy maker founded in 1869 in Bridgeport, Conn. The first trains produced by Edward Ives (later succeeded by his son Harry) were pull toys. Clockwork trains made of tinplated steel came next. Ives was moving ahead with clockwork trains when a horrendous fire destroyed its plant in 1900. Rather than surrender, the Ives family returned with a vengeance and brought out the first clockworks in the country that ran on track–specifically O gauge track (1 ¼” between the rails). The black stamped-tin locomotives and handpainted passenger cars were a stunning step forward.

Ives, influenced by the practices of Märklin and Bing, marketed its trains and system of track, switches lights, signals, and stations with ingenuity, forging ahead with a growing line of clockwork trains that had growing appeal.

In fact, Ives challenged German firms for supremacy in the early 1900s with its familiar American prototypes. These new toys looked so much better than their imported rivals that Bing, Carette, Issmayer, Märklin, and others revised what they were making for the United States so their trains more closely resembled Ives’ production.

If longtime European toy makers believed they could learn a thing or two from ives, what might a feisty young lion learn?

Young, sharp claws

Clearly the world of toy trains was already crowded when Lionel became a fledgling cub a century ago. Still. J.L. Cowen’s new company saw ample opportunities for growth as it forged ahead with a touch of fear, but a larger measure of nerve.

Lionel’s first electric trains, cataloged from 1901 to 1905, departed from the then-current gauges and ran on track that, unlike any other seen in America, measured 2 1/8 inches between the outside rails. In 1906, it again ignored the pack and offered trains that ran on track with rails spaced 2 ⅛ inches apart, a new gauge that Lionel dared to call “Standard.” Over the next 15 years, as Lionel allotted more resources to developing a complete train line similar to what Ives offered, it gradually outpaced almost every competitor, foreign and domestic.

Despite early marketing successes, Lionel didn’t exactly break away from the pack. Until war erupted in Europe in 1914, German manufacturers matched Lionel, Carlisle & Finch, and Ives step for step.

However, the disruption of trade caused by World War I hurt Bing, Märklin, and others. More damaging still was Americans’ antipathy for all German products and their support from American-made items (encouraged by the formation of the American Toy Manufacturers Association in 1916). Those firms were further hindered by Lionel’s marketing effort that proclaimed Standard gauge better than Europe’s No. 1 gauge, and disparaged lithographed trains in general and clockwork ones in particular. Never again would Europe’s toy train makers contest for supremacy in the United States.

Other feisty cubs

Lionel encountered other newcomers that also believed they could emerge victorious from the hunt by producing electric, and not clockwork, trains. While nearly all of these firms guessed wrong and disappeared in a few years, they did advance the hobby and influence Lionel in subtle and not-so-subtle ways. Perhaps the most notable of these smaller rivals was Voltamp Electric Manufacturing Co., which entered the field in 1906 or 1907. Led by Manes Fuld, this Baltimore firm offered a small yet appealing line of two-rail, 2-inch gauge trains and trolleys, complemented by striking accessories built by German toy makers. What won Voltamp trains the highest praise was their beauty. They came hand-painted and enhanced with sprung trucks and embossed wheels.

Most important, Voltamp led the way with a line that was powered by household alternating current (AC) instead of dry-cell batteries or other “portable” sources of electricity.

Other newcomers announced their arrival slightly earlier. Howard Miniature Electric Lamp Co. and Knapp Electric & Novelty Co., both based in New York, manufactured electric 2-inch gauge trains that ran on two-rail sectional track.

Knapp had been around since 1890, but didn’t enter the toy train field until 1905. It marketed cast-iron and stamped metal steam locomotives, along with passenger and freight cars, trolleys, and switches and crossovers for rolling stock for eight years. Rising production costs and heated competition forced Knapp to abandon this part of its line in favor of electrical toys and games.

Howard didn’t make it even that long, but probably had a greater impact. For one thing, it was the first to produce toy locomotives with an illuminated headlight and brass drive wheels. For another, it developed a sizable line that included four different engines and an equal number of trolleys, not to mention a pleasing array of freight and passenger cars. Gone by 1910, Howard brought out a roster that surely influenced Lionel’s.

Less influential, if only because of a lifespan even shorter than Howard or Knapp, was the Elektoy brand, introduced by J.K. Osborn Osborn Manufacturing Co., of Harrison, NJ·, in 1911. These three-rail No. 1 gauge trains depended on electricity.

Meanwhile, American Miniature Railway Co. struggled for a share of the clockwork market. Two former employees at Ives formed the company in Bridgeport, Conn., in 1909. They brought out cast-iron and tin pieces in No. 1 and 0 that were modeled after similar Ives locomotives and rolling stock.

The timing must not have been right for either firm because American Miniature Railway was out of business by 1912 and Elektoy vanished from the market the next year.

Lionel had clawed past all but two of these American rivals by 1920. Carlisle & Finch threw in the towel in 1916, giving up toy trains and sticking with its Edmonds-Metzel Hardware Co. Voltamp tried to keep the lion at bay but by 1923 Voltamp’s train line was sold to H. E. Boucher Manufacturing Co., a New York concern that laterwould be known for its gorgeous model of the Blue Comet in Standard gauge.

Strong foes, old and new

Despite the fall of the Europeans and smaller U.S. firms, Lonel still had its paws full with hungry competitors, including a seasoned veteran and a high-flying newcomer who would prove to be a mainstay.

The veteran, Ives, could justifiably be called the leading American toy trainmaker through the end of the first World War. Competition pushed Ives to take a number of risks. To start, it brought out the first American-made No. 1 gauge trains in 1904. Then to make its clockwork trains more appealing, it redesigned locomotives and rolling stock and added new series to both its 0 and No. 1 gauge lines. Third and perhaps most significant, Harry and his father announced in 1910 that they had developed the first electric O gauge trains in the United States.(Lionel waited until 1915 to expand into O gauge.) Favorable responses moved Ives to power its No. 1 gauge trains with electricity in 1912. No other toy maker in the country could boast full lines of clockwork and electric trains in one gauge, much less two.

Even before Lionel abandoned its 2 7/8-inch line after 1905, Ives saw the need to bring its freight and passenger cars up to date. Over the next decade or so, Ives expanded its rolling stock roster, resulting in longer, slimmer models with automatic couplers and additional road names. With larger rosters and cars with varying levels of detail, the company could aim product lines at diverse price points in hopes of regaining a greater share of the market. The same goal led Ives, in 1921, last accept Lionel’s challenge and introduce its own version of 2 7/8-inch gauge trains, known as Wide gauge.

Like the veteran Ives, a relative newcomer from Chicago also refused to be intimidated by Lionel’s roar.

In 1905, William F. Hafner designed an O gauge cast-iron locomotive and a lithographed passenger coach for the line of mechanical toys manufactured by the company using his name. Two years later, eager to find financial backing to expand his enterprise, he entered into partnership with William Coleman, who was affiliated with Edmonds-Metzel Hardware Co.

After deciding to concentrate on clockwork trains, they adopted the name American Flyer Manufacturing Co. three years later.

American Flyer sought to win a share of the low end of the market by producing cast-iron and sheet-metal clockwork trains in O gauge. It even marketed a cheaper brand under the

Hummer trade name. At first, American Flyer evidently aimed to compete not so much against Lionel as Ives, American Miniature Railway, and German makers of clockwork toys.

Not until 1918 did the firm supplement its line with electric trains. American Flyer improved its steam locomotives with battery-operated headlights and ringing bells. Then it developed electric-profile engines and skillfully decorated them. These beauties pulled colorfully painted and lithographed freight and passenger cars that also were redesigned to make them look longer and of better quality. Coleman handled things on his own because, in1914, Hafner split from American Flyer and launched his own business to make O gauge clockwork trains only.

For the most part, Hafner Manufacturing Co. never posed much of a threat to Lionel. Its Overland Flyer line was meant to win customers away from Ives and American Flyer at the lower end of the market, where clockwork trains and lithography remained popular.

All the same, Lionel had reason to worry that it was losing the business of families with smaller incomes. That concern grew once such mail-order giants as Sears, Roebuck & Co. and Butler Brothers started to market Hafner trains aggressively.

Big, wide cats at war

With the passing of early rivals, the 1920s gave Lionel reason to fluff up its mane and roar with vigor. Surviving competitors resigned themselves to fighting for second place in the Standardand 0 gauge markets, but Ives and American Flyer didn’t just roll over and play dead.

Ives initiated a new challenge to Lionel in the Wide gauge market in 1921, a year after abandoning No. 1 gauge. Over the next few years, it brought out both steam- and electric-profile locomotives, along with beautifully painted freight and passenger cars. Enthusiasts today celebrate a number of the Ives Wide gauge outfits, notably the National Limited, the Olympian, and the Prosperity Special. They consider them true classics, equal to anything Lionel cataloged at the time.

Unfortunately for Harry Ives, his attractive and well-built Wide gauge trains could not stave off the financial problems that dogged his family’s business. Rising costs associated with the development of new, die-cast Wide gauge locomotives and stamped-steel passenger cars, widespread distribution of the annual catalog, and generous repair policies weakened the company. Ives filed for bankruptcy in 1928.

Lionel, American Flyer, and Hafner kept the line afloat for a couple of years by using bodies they manufactured as the basis for outfits marketed under the still-respected Ives name. These desirable sets are known as “Ives-transition.”) Eventually, Lionel acquired the Ives’ assets and produced Ives trains in 1931 and 1932 in its own plant in New Jersey before putting an end to the line in 1933. The lion had devoured its chief American foe.

Out in Chicago, American Flyer entered the Wide gauge field in 1925 with a line of handsome electric-profile locomotives and lithographed passenger cars. To offset its late entrance into this market, Coleman’s company priced its trains below comparable models from Lionel and Ives yet added enameled finish, brass or nickel trim, and other features. Over the next few years, it introduced a number of outstanding sets that included the Mayflower, the Pocahontas, and the President’s Special.

Pulling the lion’s tail

Lionel felt another tug on its tail in the mid-1920s, this time from a German competitor with an American cousin. Dorfan, established in 1924 by Julius and Milton Forchheimer in Newark,NJ., had links with Joseph Kraus & Co.,a German firm that exported Fandor 0 gauge trains to the United States before World War I (“Dorfan” and “Fandor”were derived from Dora and Fanny, the mothers of the Forchheimer cousins.)

Dorfan began by marketing clockwork and electric locomotives and cars in 0 gauge in 1925; it added electric trains in Wide gauge a year later. Soon, both its lines featured different series of engines and rolling stock at various price levels.

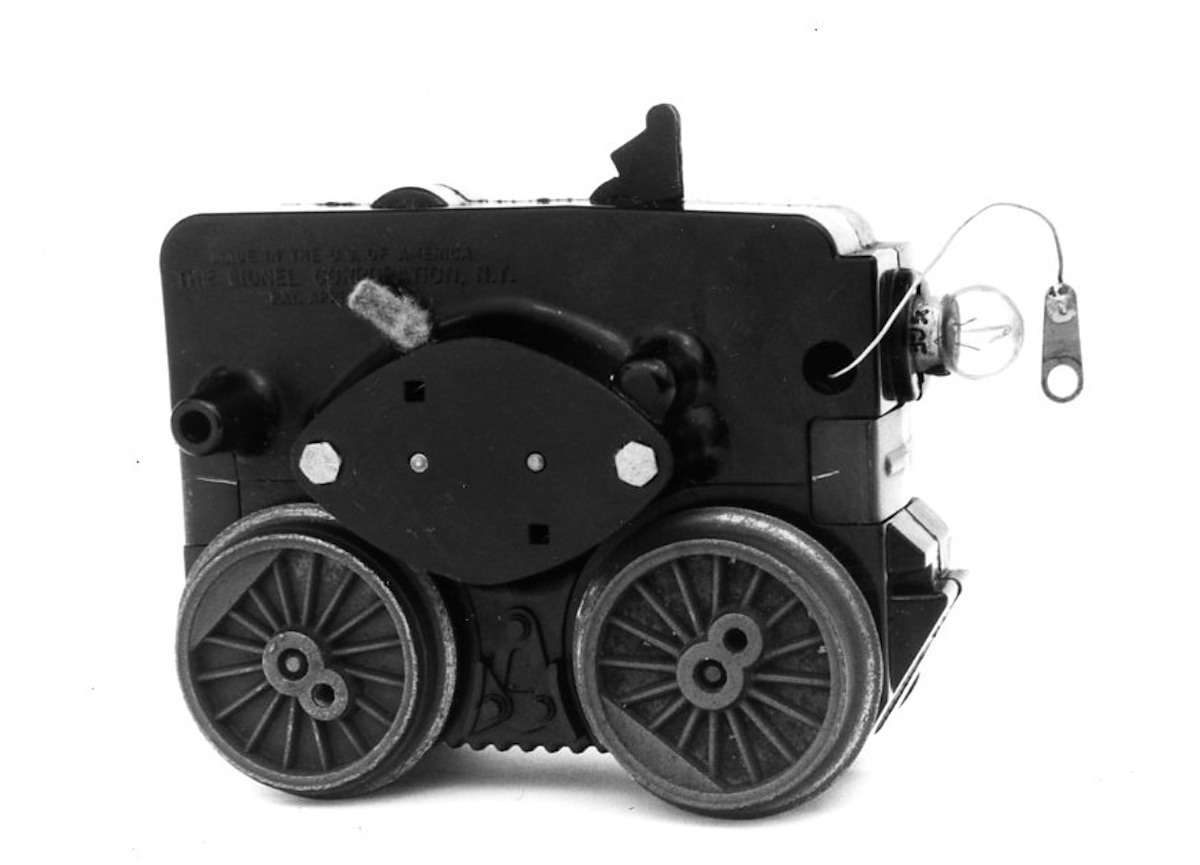

Though never a threat to Lionel’s dominance, Dorfan still left its mark as an innovator in terms of production techniques. It was the first toy train maker to rely on a zinc-copper alloy as its primary die-casting material. Using the new process of pressure die-casting, Dorfan built trains whose unbreakable body shells held their wheels in place and therefore eliminated the need for a frame. Light bodies, husky motors, and ball bearings on drive axles gave the locomotives more pulling power than their Lionel and American Flyer counterparts, which gave Dorfan quite a marketing angle.

Before many years went by, however, impurities in the zinc-copper alloy oxidized and caused the material to warp and crack until models literally fell apart. Suddenly, Dorfan’s engines weren’t so marvelous.

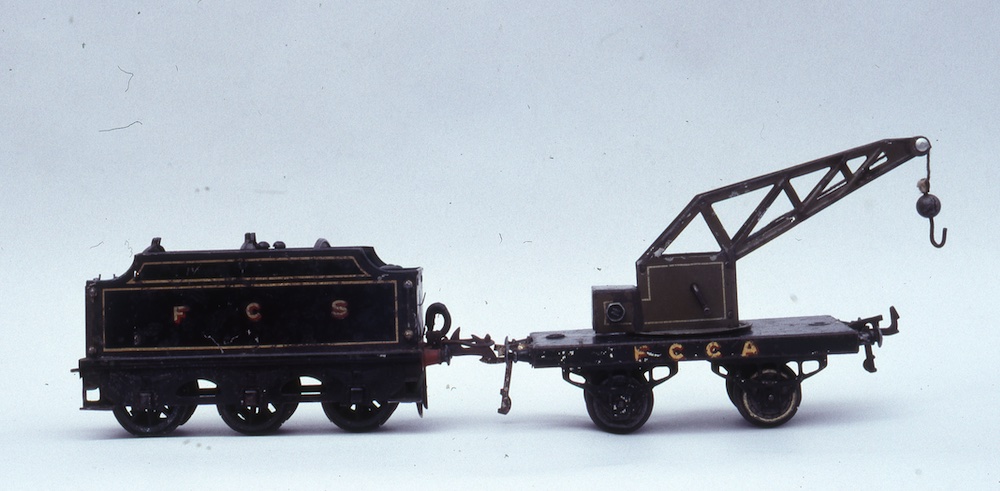

The company’s freight and passenger cars experienced far fewer problems. Whether made for the Wide or O gauge lines, Dorfan’s rolling stock featured stamped-steel bodies, superb lithography, and noteworthy details, particularly hand-painted, three dimensional figures inLionel’s prewar competitors passenger cars and the first die-cast trucks and wheels installed on toy trains.

Pulling these cars over Dorfan’s three-rail track were electric-profilei locomotives with outstanding power. The O gauge line later incorporated1 clockwork and electrically powered steam locomotives, as well as a handful of lithographed accessories.

Dorfan might have been able to carve out its own niche, but its appeal eroded due to casting problems combined with the need to lower production costs by removing details. The firm scraped by during the first years of theGreat Depression, only to quit producing trains in 1934.

By that time, American Flyer was seeking new ways to win customers. It invested in new tooling, vigorously advertised its new O gauge steam engines (including a New York Central Hudson that anticipated Lionel’s celebrated No. 700E), and upgraded passenger and freight cars. Best of all, it introduced models of the Burlington Zephyr, Milwaukee Road Hiawatha, and other streamlined trains that were entrancing people across America. Cast-aluminum versions were directed at the high end of the market, sheet-metal ones at the low end.

The future appeared bright William Coleman Jr.’s high-flying firm, so it was a shock when he quit cataloging Wide gauge trains in 1936 and sold his O gauge line to A. C. Gilbert Co. of New Haven, Conn., in 1938.

Already known for its Erector sets and Mysto-Magic outfits, Gilbert as jumped right into the toy train arena. In 1938, it marketed handsome O gauge models of Atlantic and Pacific steam locomotives and tenders under and motor the American Flyer name (almost certainly holdovers from the Chicago line). A year later, Gilbert announced the Tru-Model American Flyer brand of 3/16-inch scale trains. These highly detailed beauties included some fine die-cast steamers and several new die-cast and sheet-metal freight and passenger cars. Collectors now covet these models, the forerunners of the distinguished S gauge line that made its debut in 1946.

Claw “Marx”

While Gilbert moved American Flyer toward a direct challenge with Lionel, Louis Marx & Co. sought only to capture part ofLionel’s kingdom – the low end of the toy train market.

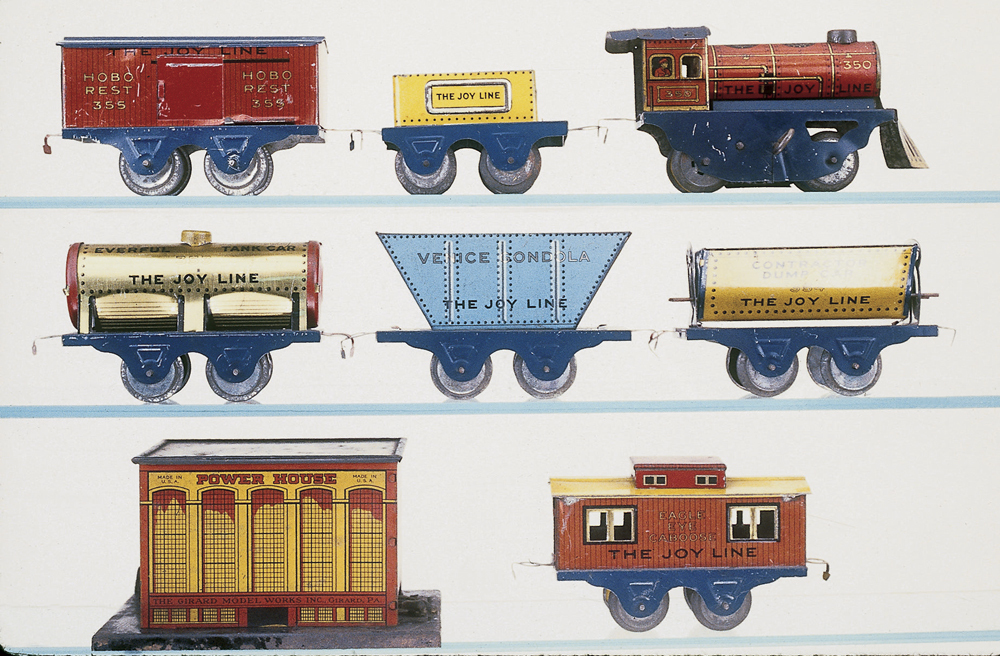

In 1928, Marx expanded its line of mechanical toys with Joy Line clockwork trains made by Girard Model Works. Tivo years later, it added Joy Line’s electric engine. Subsequently, Girard suffered financial difficulties and declared bankruptcy in 1934. At that point Louis Marx purchased control of the business, thereby strengthening his manufacturing capabilities. By the end of the 1930s, Marx had factories in Erie, and Girard, Pa., and Glendale Va., while its business offices remained in New York.

In the early 1930s, Joy Line (whether Girard or Marx) consisted of elementary types of freight and passenger cars that rode on the most basic of trucks with simple couplers. Improvements came in the middle and later years of the decade, after Marx gained control, when it brought out toylike models of. Union Pacific and other streamliners. These cost less than comparable trains offered by Lionel and American Flyer, but lacked detail and size. Marx also released bright models’ of the Commodore Vanderbilt and the Mercury, both New York Central engines, along with six-inch passenger and freight cars. As the shadow of World War II grew, Marx added military trains to its mix.

Time out for war

And so, as war came and production of electric trains ended in 1942, Lionel found itself dominating the market in ways its.leaders could barely have imagined four decades before. American firms were virtually all that competed in the toy train market, and they did so principally with O and O-27 gauge trains. German companies played a lesser role, and No. 1 and 2-inch gauge, even Standard/Wide gauge, were gone.

Except for the low end of the market, where Marx and perhaps Hafner had strength, the Lionel Corp. faced few serious challengers. The feisty lion had grown powerful and it prowled its territory with confidence. Whether any new rivals would emerge remained the big story for the next half-century.

The author wishes to acknowledge assistance provided ded by Ron Antonetti and Frank Loveland.