Manufacturer

Accucraft Trains

33260 Central Ave

Union City, CA 94587

accucraftestore.com

Price: $1,775

Paint schemes:

Black, blue, green, maroon, and gray

Features:

Dimensions: Length, 9 1/8″ over buffer beams; height, 6 3/4″; width, 3 7/8″.

Weight: 5 pounds, 6 ounces

Brass, copper, and stainless-steel construction

Two working D-valve cylinders

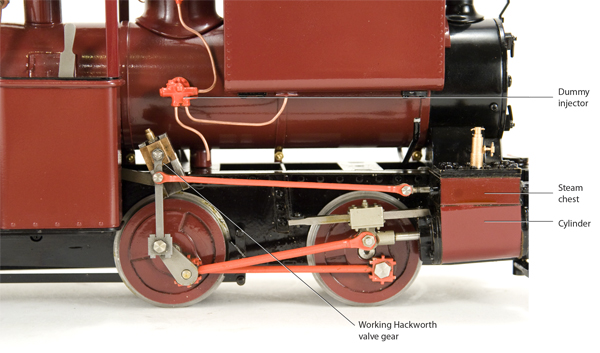

Working Hackworth valve gear, reversible by a lever in the cab

Single flue, gas-fired boiler

Blowoff pressure: 60 psi

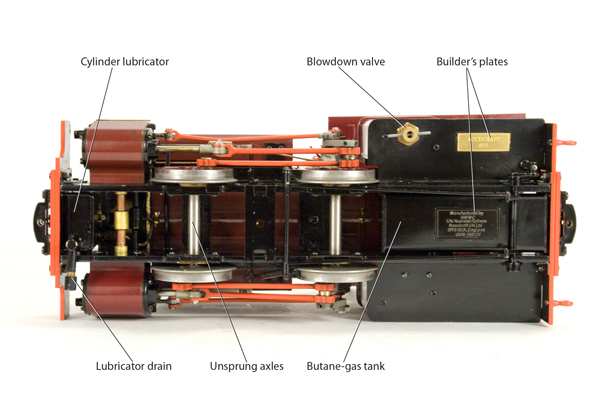

Displacement cylinder lubricator

Fittings include safety valve, water glass, pressure gauge, blowdown valve, superheater, and throttle

The prototype. Starting in 1903, they produced 163 of the diminutive “Wren” class of 0-4-0ST engines in a variety of variations. They saw service all over the world, doing light industrial work such as air-field construction, sewer construction, hauling munitions at factories, and so forth. Several of them have been preserved and are running today.

The model. Accucraft’s 7⁄8″-scale model, for gauge-1 track, is based on the so-called “new type” of engine, developed in 1915. The two-foot-gauge prototype had inside frames, Hackworth valve gear, and cast-iron wheels with shrunk-on steel tires. Accucraft’s model follows suit (except for the cast-iron drivers). It comes with a set of operating instructions, and a brief history of the company and the engine. Also included is Accucraft’s standard package of cotton gloves and assorted syringes, wrenches, and Allen keys.

An impressive model

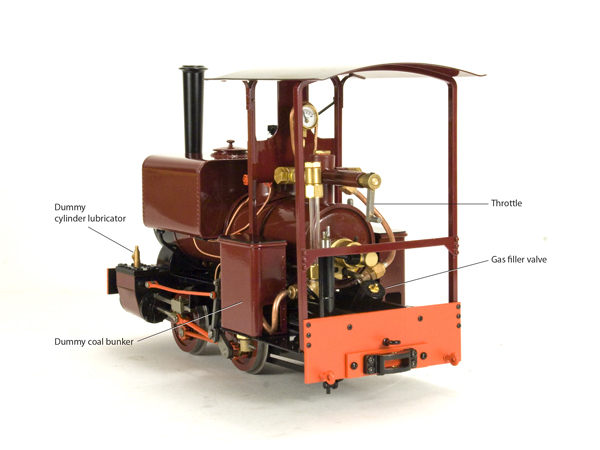

Accucraft has done an excellent job of replicating the original. Not only have the proportions been accurately captured, but much of the finer (cosmetic) detail has been included as well. The model has the prototype’s unusual rectangular water tank (in this case, a dummy) perched atop its boiler. The cab is rudimentary in the extreme, being little more than four uprights and a roof. Two small (dummy) coal bunkers reside in the cab, one on each side of the boiler.

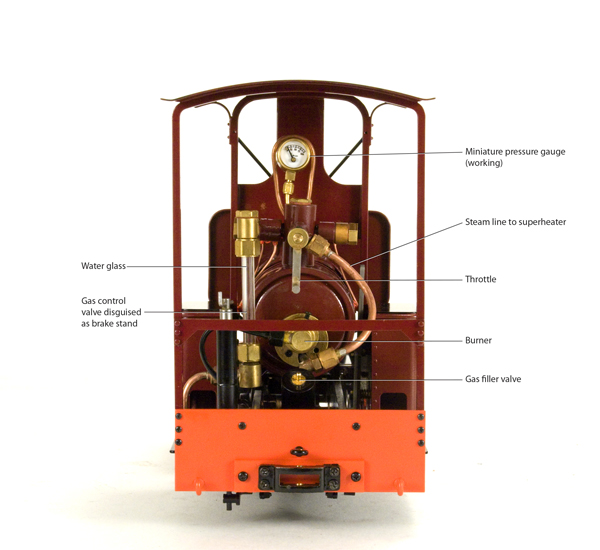

Our review sample is painted maroon and black, with crimson end beams, dummy valve handles, and other details. The level of construction is quite good. Paintwork is excellent and the detail level is high. All machine work is neatly done and there is no evidence of excess solder in any of the joints. Backhead fittings include the throttle, a large water glass, and a pressure gauge, with the nice added detail of the steam line to the gauge looping over the top in a prototypical manner. The ½”-diameter gauge is nearly scale for this engine. There is also a blowdown valve beneath the coal bunker on the left side. This is connected to the lower leg of the water glass, so can be used to momentarily blow down the glass (if it should get a bubble), as well as blowing down the boiler at the end of the run.

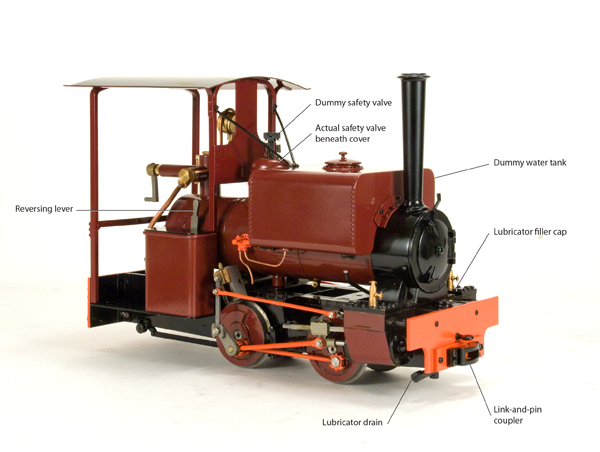

A dummy safety valve sits atop the steam dome. The actual valve is concealed beneath the dome cover, and exhausts through two small vents there. The vent holes can also be used as grab holes for a pair of pointy pliers or tweezers, to unscrew the top of the steam dome for access to the real safety. I tried it, just for grins, and found that the dome top unscrewed easily.

The locomotive is gas fired with butane. The small fuel tank is under the footplate, which is far enough away from the boiler that the heat shouldn’t affect it much. The filler valve projects upward from the footplate and toward the rear at about a 45° angle. You’ll need a little extension on your gas filler to reach it. The control valve for the gas to the burner is on the left side of the footplate, disguised as a brake stand.

Two D-valve fixed cylinders power this engine. Reversing is achieved via Hackworth valve gear, which is not often seen, though perfectly feasible, on model engines. The gear is controlled by a lever on the right side of the boiler, in the cab. There are three positions: full forward, neutral, and full reverse. Unlike Walschaerts or Stephenson’s valve gear, Hackworth is an industrial (as opposed to mainline) gear that does not lend itself to notching up, so the three-position reverser is perfectly prototypical.

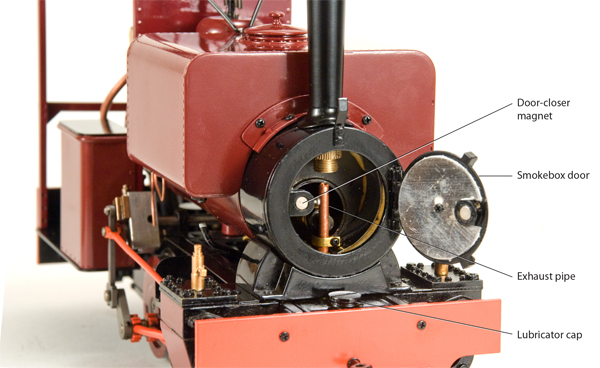

At the front of the engine, beneath the smokebox door, is the lubricator filler cap, accessible with a screwdriver. On the right side of the engine, just below and in front of the cylinder, is the lubricator drain. The lubricator should be drained of water and refilled with steam oil before each run.

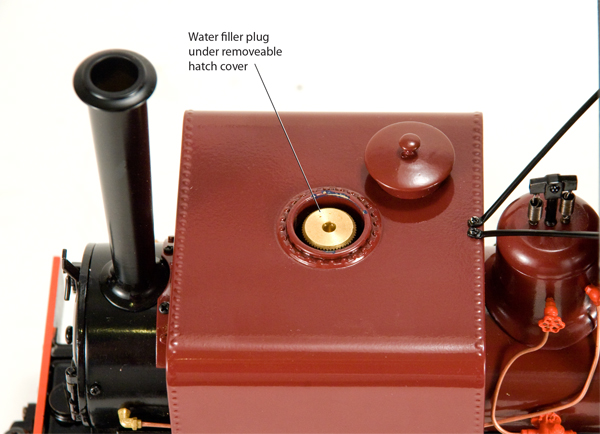

The boiler filler plug is located under the dummy hatch cover on top of the square tank. The instructions say, “Lift the dummy cap off and undo the knurled cap with a screwdriver to fill with water.” The problem was that there was no screwdriver slot in the cap, and the cap was buried in the tank. Using a pair of fine-nosed pliers, I was able to unscrew the cap. I immediately cut a screwdriver slot into it. After that, all was good.

To light the engine, the smokebox door must be opened, the gas valve cracked, and a fire or spark introduced into the smokebox. The fire should catch immediately and flash back into the flue. The smokebox door, according to the directions, should be left open for a couple of minutes, after which time it may be closed. Strong, tiny magnets keep the door closed—an improvement over Accucraft’s usual door clips.

verall, this engine looks great. But how does it run? First, I read the instruction manual. It suggests a couple of things you might not be used to. One is starting the engine in reverse, which is supposed to help in clearing condensate from the cold cylinders. The manual is well written and has a lot of good tips, especially for beginners. Read it.

Preparing for a run

Before firing up the engine, I oiled all of the moving parts with a lightweight machine oil, then I filled the displacement lubricator with steam-cylinder oil. After that I filled the boiler with distilled water until it showed about three-quarters full on the water glass, as per the instructions. Finally, I filled the gas tank with butane, using a long-snout filler.

I opened the smokebox door, then cracked the gas valve a little until I could hear the escaping gas in the flue. I lit it off and the fire immediately popped back into the flue as expected. While waiting for pressure to come up, I did a quick look around to make sure the track was clear.

Pressure was up to 40 psi in around eight minutes. I put the engine into reverse and opened the throttle. Nothing happened. The mechanism on our review sample was somewhat stiff, which was concerning. I rocked the reverse lever back and forth a couple of times. All of a sudden, a geyser of water and steam oil was ejected from the stack and the engine showed definite signs of life. After a little more cylinder clearing, it was off.

Off and running

The first run around my loop was alarmingly fast, despite my 13-foot-radius curves. I snagged the engine as it passed and closed the throttle some. The throttle spindle has an O-ring on it to seal it. This causes a little bit of “springback,” which means that it’s difficult to precisely set the throttle. You must open or close it just a little more than intended, so it will spring back into position. A longer throttle lever would help. I was able to close it enough that the engine traveled at a more sedate speed. The lumpiness in the motion was still evident but, despite this, the engine ran well in both directions.

The second run was better. I filled the boiler to two-thirds of a glass instead of three-quarters. When the throttle was opened the first time, much less condensate was ejected. It was easier to get the engine started, and a more satisfactory run was achieved. Like every miniature steam locomotive, this one must be learned to get the best performance.

By the third run, the mechanism had worn in some and was running more smoothly. I was learning the best throttle setting for a reasonable speed. I timed this run. Pressure was up to 40 psi in around seven minutes. The actual run lasted another seven. Thus, the run is limited by the duration of the gas tank, which is around 15 minutes. This can vary depending on burner setting, ambient temperature, and load, but this running time is acceptable for a small engine.

One thing that can be done to increase the actual running time is, once pressure is up, to shut down the fire and refill the gas tank. I did this on the fourth run and got a solid 14-minute run out of it.

For the fifth run, the smoothest yet, I gave the engine a load of a single open car filled with three or four pounds of scrap iron. The “Wren” easily walked away with this burden and could have easily handled much more.

Because of the minimal cab, this would be a difficult engine to radio control inconspicuously. There are no obvious places to hide servos, receiver, and batteries. I’m not saying it can’t be done, but I think you’d have a hard time concealing the gear.

Accucraft’s “Wren” is a quintessential British industrial locomotive. It runs great and is remarkably quiet for a gas-fired engine. Because it has an open cab, accessing the controls is a joy. Accucraft has done an excellent job in capturing the character and spirit of the prototype in this a good-running machine.