Hide the mechanics

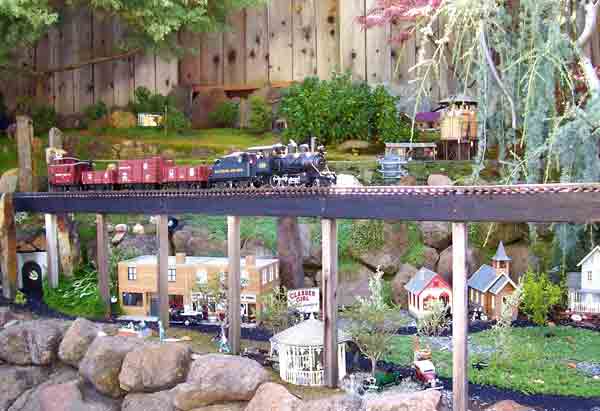

The surveyors and civil engineers of the Vista del Bahia Railway (photo 1) rose to the challenge of respecting the integrity of the natural setting and lush gardens already in place. In fact, when trains aren’t running, it’s difficult to find the roadbed or see where its owners, Steve and Darci Smith, installed 300′ of track. Much of the dual-track mainline seems to float along the top of a hedge.

Where the dogbone trackplan opens up to a loop, he needed another technique. On the bottom of his roadbed bench of ripped bender board (plastic lawn edging), mounted on metal fence stakes, he drills holes for wires to support clinging vines (photo 2). Along a fence, he arched a chicken-wire frame to support a tunnel of vines.

As our bodies age, our railways can evolve to keep us active in the hobby. By necessity and for the love of running trains, John and Janet Morrison retrofitted their gardeny, ground-level Dunckley Northern Railway (GR, June 2008) into a beautiful, all-benchwork railway. Shrubs and taller plantings replaced their low garden, although groundcover still flourishes between posts and pathways. Now Japanese maples, with their lacy leaves, provide a canopy over the roadbed in several areas, forming green tunnels (photo 3). Even their rail yard got a makeover on a chest-high platform (photo 4). It makes sense to place industries where plants can’t grow. By consolidating the rail yard near the house, the busy scene captivates our attention and provides a handy transition from their indoor rail yard. As a bonus, the scale, post-raised office, water, and fuel tanks camouflage the fence.

After completing a miniature town for their Heavy Metal Railroad, Gary and Carol Garnas circled their yard with a long “fence” doubling as roadbed. You could say they hid the benchwork in plain sight because trestling fills the gaps between every post (photo 5). The fine trestlework scales down this rugged large-radius benchwork, and trains are assured a fast ride back to town.

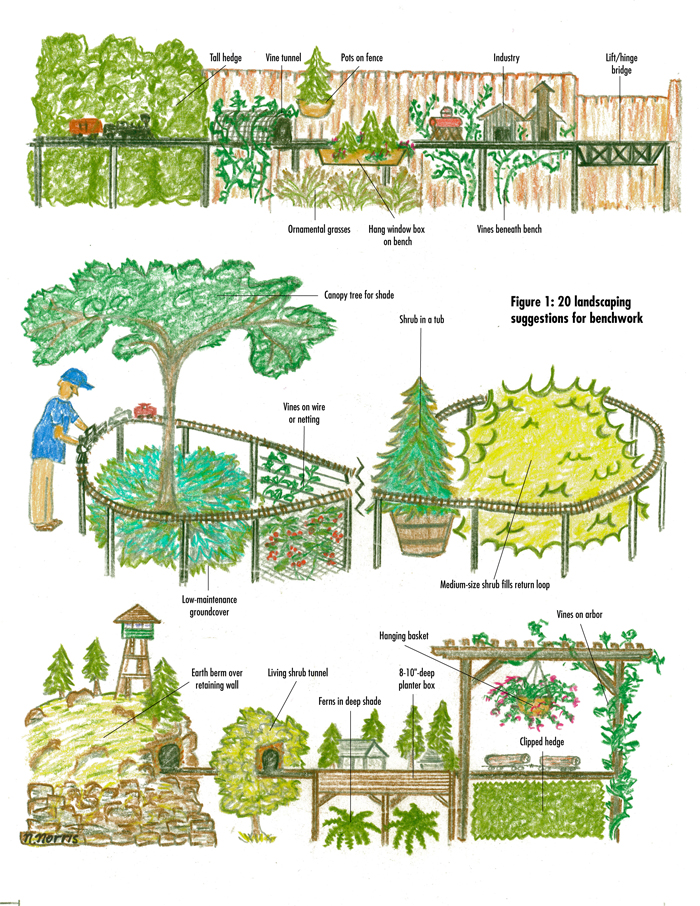

Different like snowflakes

The regional gardening reports and photos 6 and 7 depict some of the many construction/planting choices, also sketched in figure 1. For example, Pete and Carol Comley’s mostly benchwork railway needed access for the lawn mower, so they built an arched bridge over that opening in the lawn (photo 6). Then they planted their arborvitae hedge just behind the benchwork in this sunny spot and grew ivy vines on a shaded fence.

Conversely, Pat and Jo Ann Peterson run trains just behind their clipped hedge (photo 7). From that benchwork, curved girder bridges turn the trains past a wooded garden on the way to more benchwork along the house, where trains travel through the guest bedroom.

Dave Hartwig needed a spur to show off his detailed logging industry, so he built a raised planter box along a walkway (photo 8). With no room for an earthy landmass, the gardener in him built the box strong enough to plant trees around the sawmill and greened it underneath with ferns.

Plumbers will use PVC pipe for posts, carpenters will choose pressure-treated wood, welders like metal, and the handyman will find something stashed in the shed on which to run trains. It’s up

to you—hide the sub-roadbed or flaunt it. Take a look at your specific needs and where the train has to go, to make it as accessible and pleasing, as your purse allows.

Regional gardening reports

Zones listed are USDA Hardiness Zones

Question: What techniques help to keep the mystique alive when hiding the mechanics of your non-scale roadbed?

Doug Matheson

Manotick, Ontario, Canada, Zone 4

Multi-engineering

My prior experience of regularly running trains on a mostly elevated railroad influenced my decision to build elevated track—it makes operating and working on the railroad so much more pleasurable. But I also wanted a garden, to increase the pleasure of being in my own little world. Because of the rather ponderous look of pressure-treated 2 x 8″ roadbed on 4 x 4″ posts set into deck blocks within the garden, I’ve evolved four strategies for integrating the railroad:

• Lattice. In areas where the track must be handily reached, I’ve used a wooden lattice, often hiding parts or all of it with ferns (I garden in the shade, hence the choice of planting).

• Terracing. In other areas, I’ve raised the garden using walls, rockeries, or eathern berms.

• Grading. I’ve sloped the railway roadbed up on a more gentle angle where there is enough space.

• Spanning. Lastly, to avoid really extensive earthen berm-like gardens, I have spanned raised gardens with some lengthy bridges. In one place, a 16′ span of four deck-girder bridges crosses my garden 30″ above ground, while, in another place, a bridge made of three trusses spans 24′ at a height of 20″.

Ultimately, the goal is to provide a pleasing garden space in which to enjoy operating trains, hiding the unsightly heavy construction needed to achieve it.

Ray Turner

San Jose, California, Zone 9

It takes thyme

Mystic Mountain Railroad gains elevation on a steep part of my yard via a 412-turn double helix in an area about 12′ x 15′. I covered the visible part of the helix with concrete rock castings. While this is a point of high interest on the MMRR, it does create a large area of bare rock, and I wanted to soften it a bit. I chose to mount a planter on the backside (interior) of the rockwork, where it can’t be seen from the front. I planted thyme, which will eventually hang over the edge of the rockwork to break it up with some green. The planter is fed from a drip-watering line with another tube for a drain to the ground, so it doesn’t water the tracks below.

Frank Lucas

Pleasant Hill, California, Zone 9

It takes two

I must admit that I was impatient to get a train running when we built our garden railroad, so I took many shortcuts (which I must now do over, the right way). I laid the track with little thought to greenery or scenery but I did get my little Mogul running around just 12 months after we started. One day, while I was happily doing this, Donna appeared with a paintbrush in one hand and a can of black paint in the other, and attacked the bender-board (plastic lumber) garden edging that I used to create the elevated section above the village. Voila! It is now a girder bridge that spans the open space and disappears beneath our Japanese maples.

Bill Hewitt

Mansfield, Massachusetts, Zone 5

Hedgerows

We used dwarf barberry to line the sides of our raised line in the European section of the Southpark & Dogbark Garden Railway. It requires frequent trimming to maintain but works beautifully to hide the raised roadbed. In other areas, a perimeter hedge of this thorny plant keeps our dogs at bay.

Christina Brittain

Washougal, Washington, Zone 6-7

Veering vines

Christina Brittain photo

Many annual vines, like nasturtiums, grow too large for our Quinn Mountain Railroad. However, there are a few with good scale proportions. Some climb with their own supports—twining stems or tendrils that easily ascend bare, vertical, metal and wood surfaces and trellises, or cascade down benchwork and rock walls.

Our favorite small vine is black-eyed Susan (Thunbergia alata, Zone 9-10), which produces black-centered yellow flowers until the fall frost. It takes heat well, full sun to part shade, and moderate water. Seeds can be started indoors in early spring or sown outdoors after the last frost; they may self-seed in zones warmer than Zone 5.

We discovered this vine after installing a unique curved stone as a short tunnel. We supported it over the tracks by drilling two holes (1″ deep, 10″ apart) into one end of its underside, driving 12″ rebar into the ground, then setting the drilled holes onto the rebar. A narrow, vertical rock now disguises one rebar and a black-eyed-Susan vine the other.

Earth islands

View a gardeny railway of raised planter “islands” growing miniature scenery. Larry Staver’s Steamup hosted dozens of steamheads. They ran their live-steam trains from indoor benchwork onto outdoor benchwork, which bridged mountain scenes built on affordably constructed retaining walls.

http://youtu.be/_9ashTZMVoo