Pat Ottensmeyer, the late Kansas City Southern chief executive, had a favorite saying: Service begets growth. It’s not the most catchy phrase you’ll ever hear. But it’s true.

And nowhere is that more apparent than in New England, where Genesee & Wyoming’s Berkshire & Eastern is growing a bumper crop of freight in the middle of what for decades has been a traffic desert.

Before we get to the turnaround story, it’s important to understand the landscape and some complicated railroad history that led to B&E running the Pan Am Southern.

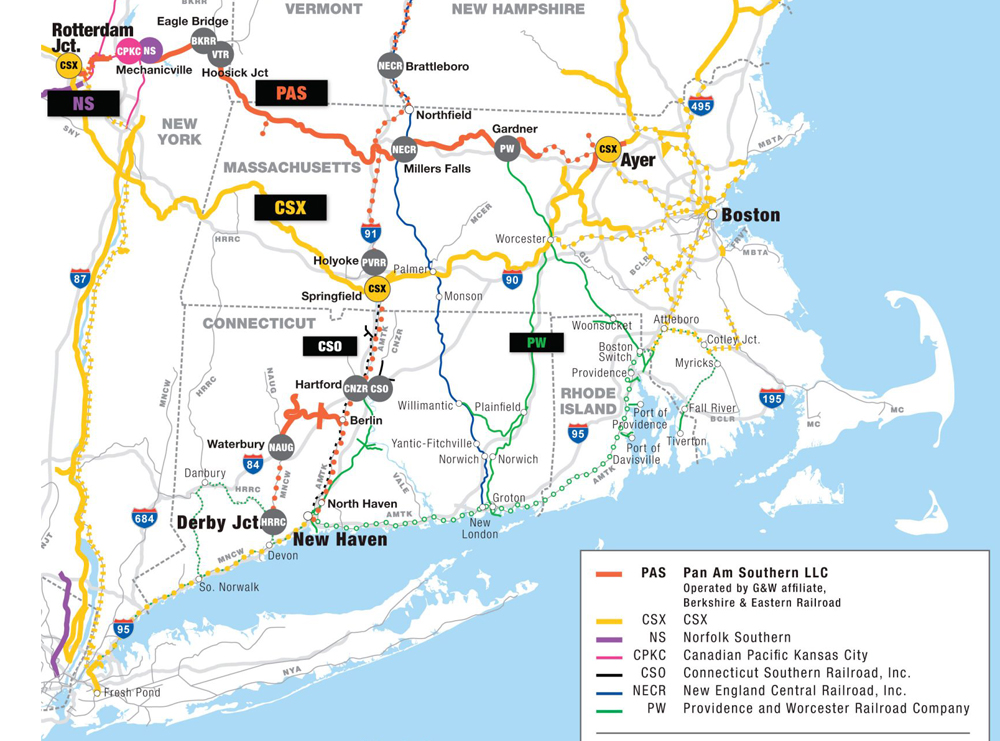

To provide Norfolk Southern with a direct route to New England, the Pan Am Southern was born in 2009 as a joint venture between Pan Am Railways and NS. The cross-shaped regional includes 414 miles of mostly former Boston & Maine trackage. It stretches from the Albany, N.Y., area to Ayer, Mass., 40 miles northwest of Boston, along with a north-south route through the Connecticut River valley in Vermont, New Hampshire, Massachusetts, and Connecticut, plus isolated trackage in Connecticut.

Pan Am Railways’ subsidiary Springfield Terminal ran the Pan Am Southern. Over the years the railroad eventually suffered from benign neglect, was speckled with 10-mph slow orders, and was chronically short of train crews. Things got worse when the pandemic hit in 2020 and Pan Am was compelled to cancel conductor training classes.

Freight just sat. Service was so poor for so long that customers with other options had largely abandoned the railroad. They either shifted freight to trucks or went to great lengths to route carloads around the regional.

On Sept. 1, 2023, the B&E became the neutral operator of Pan Am Southern, 16 months after NS rival CSX acquired PAR and became a partner in the PAS. The startup did not go smoothly. B&E had only 67 people in train and engine service when it needed 90.

Within three months, however, B&E’s crew boards filled up. The NS intermodal, auto, and merchandise trains began running on time and no longer required unplanned recrews. That freed up crews to provide reliable local service and keep cars pumping through the heart of the railroad, East Deerfield Yard in western Massachusetts. The 10 mph slow orders have been whittled down from 35 miles to just 7, with the bulk of that in and around the 4.75-mile Hoosac Tunnel.

The railroad’s 60 customers began to notice that B&E was doing what it said it would do: Show up on time and run a safer, predictable railroad that you could rely on. “The word was getting out in the marketplace that the Pan Am Southern can move trains,” says Jim Speed, the B&E’s director of sales and marketing.

The railroad rebuilt relationships with customers, who began rewarding the B&E with more business. Limestone slurry traffic came back first, followed by propane, scrap metal, grain, municipal waste, and finished vehicles. By the end of 2024, traffic had grown 28%. Through the first 10 months of 2025, traffic is up another 24% — and up 10% on B&E’s seven connecting short lines.

Those are huge figures for New England, where railroads have eked out a hardscrabble existence for decades as mill towns became former mill towns. Yet the growth didn’t surprise Blake Jones, G&W’s East Deerfield-based divisional vice president. “I thought the growth was here,” he says, based on his experience at G&W’s Rapid City, Pierre & Eastern, a similar service turnaround.

None of this is rocket science. “It’s Railroading 101,” Jones says. He adds: “There’s two priorities on this railroad. Safety and customer service, period.”

There was fear in some quarters that Pan Am Southern’s importance would diminish when Norfolk Southern shifts its daily Chicago-Ayer intermodal train pair to a faster, double-stack capable trackage rights route on CSX.

But guess what: B&E’s carload traffic has grown so much that NS has been running extra sections of its Binghamton, N.Y.-East Deerfield merchandise train three times per week. When the intermodal trains depart the Pan Am Southern, they’ll be replaced by a new daily merchandise train pair.

The B&E is proof that Ottensmeyer was right — that service does in fact beget growth. “One hundred percent,” Jones says.

You can reach Bill Stephens at bill.stephens@firecrown.com and follow him on LinkedIn and X @bybillstephens

— To report news or errors, contact trainsnewswire@firecrown.com.

Two thoughts.

1. It’s worth noting how CSX and NS just let things fall apart on PAS. Three rules for success are. 1) show up 2) know what you’re doing 3) pay attention.

2. Carload bounce back is interesting. But, it is a bounce back. This is recovery of previous customers, not growth from new ones. Car load is still dying and transitioning to boutique business.

Okay, a third one.

3) why extra sections of merchandise trains? No DPU thru Hoosic tunnel?

Don, at some point B&E may seek funding for repeaters that would permit DPU use through the tunnel.

Something is happening up here in Vermont. VTR is running 100 car trains from Ruland to the B&E at Hoosick Jct. Three times a week (???)

The Rutland never ran trains like that.

Nice to see “Safety and customer servive” instead of shareholder and OR.

Serve customers the way they expect and growth follows. The class 1s are so focused on “maximizing shareholder value” that they’ve lost sight of what really drives market share and growth.

New England was vehemently truck territory in the post-war years. Now it’s a matter of seeing how far the turnaround will go.