NEW YORK — BNSF Railway, Canadian National, and Canadian Pacific Kansas City are touting interline partnerships as a way to gain new volume without having the regulatory and service-meltdown risks associated with a merger.

But Union Pacific and Norfolk Southern say alliances are built on a foundation of sand, and can shift with the whims of each railroad in a partnership. “They just don’t hold up like one company that manages everything,” UP CEO Jim Vena told the RailTrends conference on Friday. “And they end. It’s as simple as that.”

Controlling service from end to end is one of the main selling points for UP’s proposed $85 billion acquisition of NS, the railroads have said.

Michael R. McClellan, Norfolk Southern’s chief strategy officer, drove that point home at the conference by going over the history of interline partnerships that have endured — or fallen apart — since the 1990s.

Since his days at Conrail, McClellan has been involved in 19 interline partnerships, from the creation of the EMP container pool in 1994 to the joint UP-NS intermodal service announced in September that links Louisville, Ky., with points on UP.

Eleven of those alliances are still in place today, including three joint ventures that are essentially permanent partnerships. “They’re all kind of operating,” McClellan says. “Some of them are doing great, some of them are kind of wobbly.”

Under the right circumstances, alliances can and do work, he says. But they are fragile: “These things can be temporary. And they change a lot,” he says.

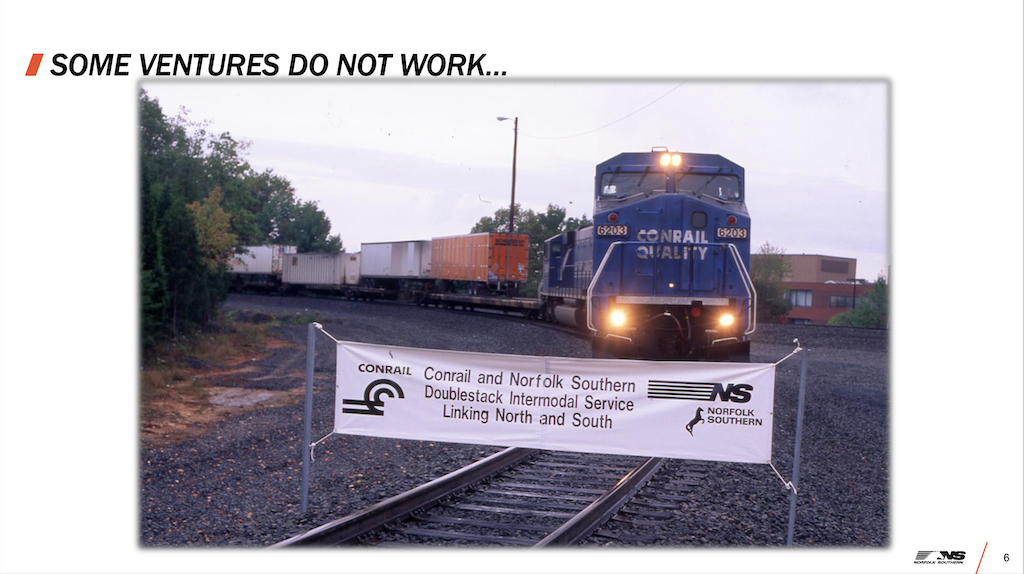

The classic example of a partnership that floundered right out of the gate was the 1995 deal between NS and Conrail for joint double-stack intermodal service linking Atlanta and Northern New Jersey via their interchange at Hagerstown, Md.

McClellan showed a photo of the inaugural run, with two Conrail locomotives on the point of a single-stack intermodal train heading for the traditional first train banner that was stretched across the tracks in Manassas, Va. The banner proclaimed “Conrail and Norfolk Southern Doublestack Intermodal Service Linking North and South.”

Look what’s missing, McClellan says: “Our inaugural double-stack train had no double stacks on it.”

What the photo didn’t show, he says, was that the first train was three hours late. Rather than break through the banner, as intended, the train ran over it. Scrawled on the side of one of the locomotives: “Jesus Saves and Clinton Sucks.” Those things may be true, one executive quipped, but you don’t need to put that on your locomotive.

The final indignity? The anchor customers on the service were J.B. Hunt and APL — but none of their containers were on the train. Instead, the train was hauling boxes from rivals Schneider and EMP.

“That was an inauspicious start,” McClellan says.

None of the executives gathered trackside had smiles on their faces. “The Conrail people were embarrassed. The NS people were unimpressed. And the shippers were pissed,” McClellan says.

McClellan’s father, longtime NS strategic planner Jim McClellan, said it was apparent that if Conrail didn’t care enough to get the inaugural run right they wouldn’t have a commitment to the service over the long run.

He was right. The interline service never worked. Given the choice of how to best use containers and well cars, Conrail would make the rational decision to prioritize the 900-mile run to Chicago instead of the 250-mile run to Hagerstown for its portion of the New Jersey-Atlanta service. “It was a terrible move for them,” McClellan says.

It’s a similar dynamic today in the watershed area, the swath of territory within a few hundred miles of the Mississippi River, the de facto dividing line between the Eastern and Western railroads. UP and NS say that by merging and eliminating interchange friction and short hauls for one or both railroads, they can pick up significant growth from the watershed.

What made a difference in the Atlanta-New Jersey lane was the Conrail split between CSX and NS.

“This never took off until we took over Conrail. We got this lane right, and now this is really one of the foundational intermodal lanes in our network,” McClellan says. “It would have never happened had we not acquired that part of Conrail.”

Each railroad in an interline agreement always works to protect its own interests, McClellan says, and are reluctant to invest when there’s no guarantee of an adequate return.

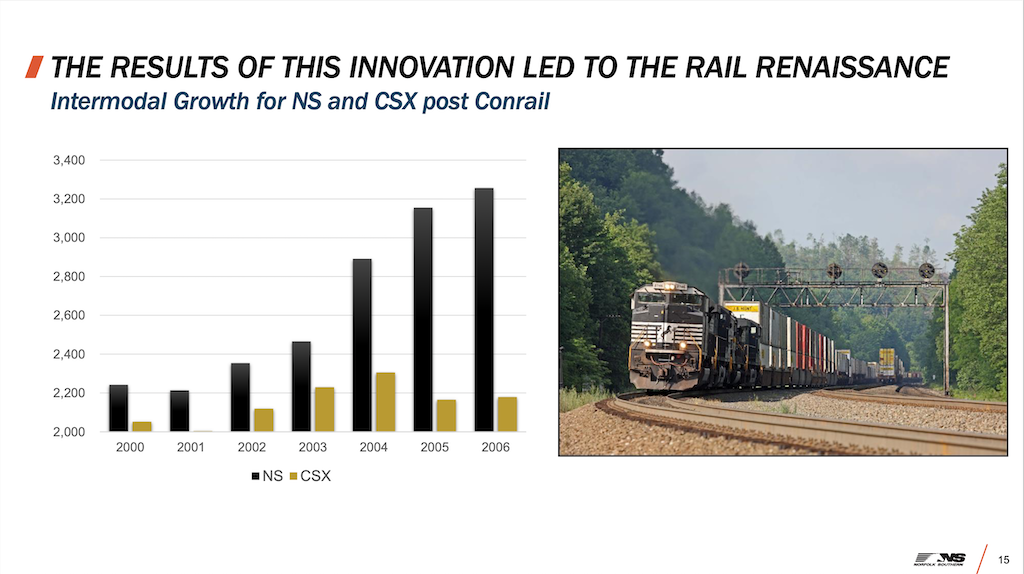

After the Conrail transaction, NS went on to make significant investments in intermodal corridors and terminals across its expanded network, which after a decade had led to 2.2 million additional container and trailer loads per year, McClellan says.

The UP-NS merger should unleash similar investments and growth and be a turning point for the rail industry, McClellan says. “The UP and the NS are going to spend a lot of money doing what we need to do, which is grow this business,” he says.

Earlier in the conference, BNSF Chief Marketing Officer Tom Williams touted the BNSF-CSX haulage rights deal that gives BNSF direct access to the Fairburn terminal outside Atlanta via the railroads’ interchange in Birmingham, Ala. The deal was signed in 2006.

BNSF and CSX built on that agreement in August, when they launched new interline service linking the Southwest and Southeast. This month they expanded the partnership by connecting Los Angeles with points on CSX in the Midwest and Northeast.

Several longtime rail executives say they have never seen so many new partnerships crop up as have been announced in the last couple of years. They include the CN-UP-Ferromex Falcon Premium service, CPKC and CSX service linking Mexico and Texas with the Southeast, and CN and CSX joint international intermodal service from Prince Rupert, British Columbia, to Nashville, Tenn., via their interchange in Memphis.

Surface Transportation Board merger review rules require merging railroads to show that projected merger benefits cannot be achieved in other ways, such as alliances.

RailTrends is sponsored by independent analyst Anthony B. Hatch and trade publication Progressive Railroading.

— To report news or errors, contact trainsnewswire@firecrown.com.

It sounds like the person or persons responsible for the CR-NS partnership mentioned in the article should have been fired for having dirty locomotives, late train, fallen banner and the competitor’s containers aboard. I guess it was a feel good moment that CR-NS would start a new service but really didn’t want it in the first place. What a disappointment….

It would be interesting to see the growth numbers broken out by lane. I think NS is talking about (6) lanes, at 1000 units a day, to get to the 2.2 million increase. But that would only be 500 container/trailer units a day per direction, which would only be about 8% of the trucks on the parallel Interstate Highway. I wonder if they have kept up their % since 2000 relative to highway traffic?

Mike’s an optimist!

He would know, more than anyone – considering his job in the mid-1990s, that Conrail had nearly zero money to invest in anything in the 1990s. Expanding intermodal terminals to keep up with demand meant gravel parking lots, not pavement (don’t have to do run-off control) and bare minimum extensions of pad tracks. And bottom of the barrel contract terminal operators with falling apart Piggy-Packers.

Someone should note, that those locos in the photo are only 2-3 years old – dirty or not. Also, the NJ to Chicago traffic revenue was about $900 a box – with four crews, NJ to Atlanta about $600 (total) and 6(?) crews.

Interline service is a matter of will, and paying attention – as is service in general.

Money for transformation is a matter of having the cash – UP and NS do – and strong leadership – UP and NS don’t. The private equity folks will always have sway with them.

UP doesn’t have strong leadership. Funny, that is not what the analysts say. Its is because of Jim Vena that the analysts are lining up behind the UP acquisition of NS. You don’t make lots of money without having strong leadership…

I agree on the barbecues intermodal terminal comment. The Pittsburgh, PA terminal when built in 1996 had dirt loading ramps that were an absolute mess, 2 Pad tracks that are too short, especially today and the usual packer machine breakdowns. Sadly, the Pittsburgh Terminal had plenty of property to have a bit larger facility. And it still does, utilizing the former PRR Pitcairn Yard property.

Don, you hit the nail on the head!

My reply should say “bare bones intermodal terminal”, not barbecue, darn auto-correct.

Ask McLellan how the Crescent Corridor is doing nowadays. PSR has done nothing but close terminals and reduce service frequencies. And now, they will have to contend with a CSX route that can run double stacks.

It’s not difficult to debunk this argument. The only service a PSR railroad is interested in is one that it has total cost control over. That way, they can fulfill their big-bank mentality by sitting and waiting for customers to crawl up to use a subpar service offering merely because it exists.

J.B. Hunt recently publicly celebrated the 30th anniversary of their now famous partnership with Santa Fe now BNSF Railway. Like most relationships (ex. marriages) there have been a few bumps in the road but so far it is working great. JBHT now controls 25% of the domestic intermodal marketplace.

And don’t forget this partnership stated out with a simple handshake between two decent and honorable businessmen. We ran the business for almost two full years without a formal contractual agreement.

JAMES — We go into the Thanksgiving holiday having read your positive and uplifting post about a handshake between “two decent and honorable businessmen”.

I remember when we had an emergency at work, a structural failure. No time to solicit bids or write a contract, let alone go through all the legal procedures. Even though I was new at the job and had no certainty how my managers would react, I called a contractor to ask for help, a man (R.I.P.) who I knew to be an honorable man and a devout Catholic. The contractor agreed. I took it to a manager. The manager and the contractor sealed the deal with a phone call. The next day, heavy equipment and sheriff’s squad cars mobilized at the Milwaukee County sheriff yard in Wauwatosa and moved down the road. Eventually, the contractor was paid and I learned the value of trust.

Charles, the funniest part of the story is that when J.B. reached across to shake Mike’s hand he said “I think we got ourselves a deal” in that wonderful Arkansas drawl of his. However, Mike now recalls that neither one of them knew what the “deal” was at the time.

I often wonder if these partnerships work out well would they inevitably lead to a merger?