WINNIPEG, Manitoba — Rail creep was detected and track buckling was likely involved in the derailment of a Canadian National grain train near Devlin, Ontario, in June 2025, according to a Transportation Safety Board of Canada investigation report released today (Tuesday, Feb. 3, 2026).

The track issues reflect the forces exerted by heavy-tonnage traffic, most of which is moving in a single direction, the report indicates.

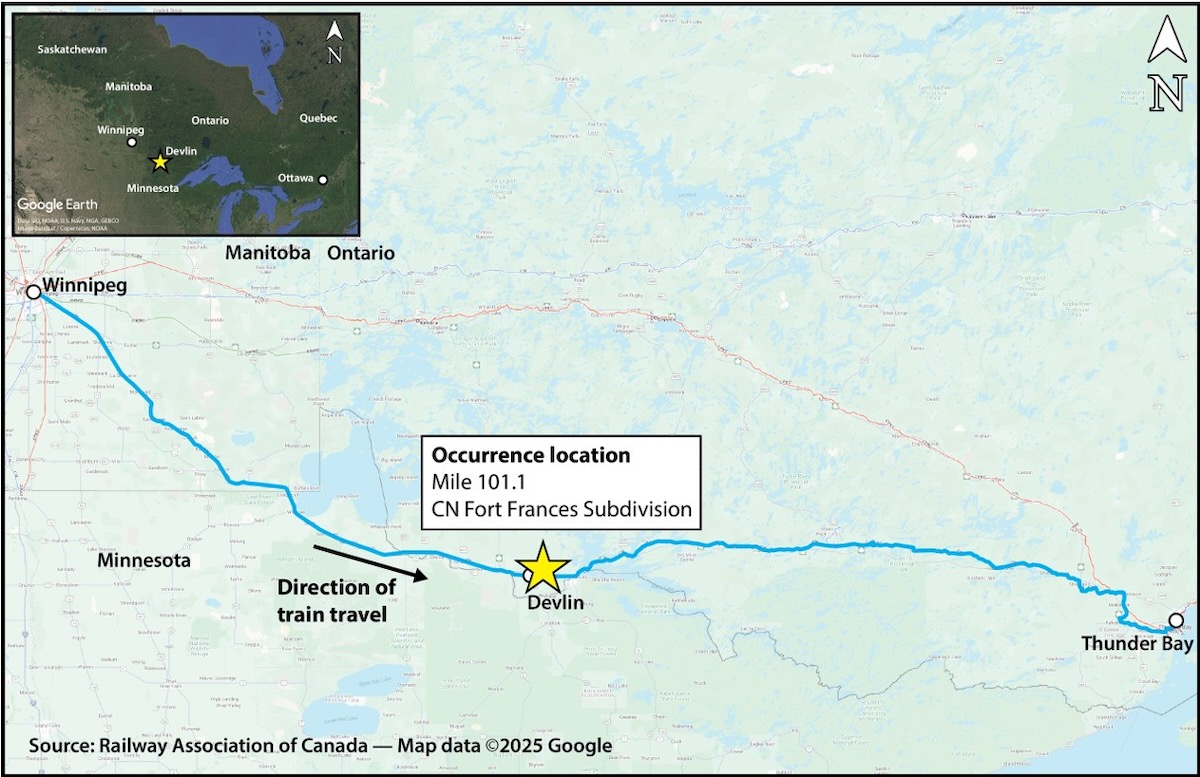

The June 28 derailment occurred at mile 101.1 on CN’s Fort Frances Subdivision, and involved a 134-car grain train eastbound from Winnipeg to Thunder Bay, Ont., with one locomotive on the head end and one distributed power unit at the rear. The train was 7,853 feet long and weighed 18,578 tons. It was traveling around a curve at 41 mph when a train-initiated emergency air brake application occurred about 1:40 p.m., after which the crew found 13 cars had derailed near the end of the train, in positions 119 to 132. Most were extensively damaged and spilled their cargo. There were no injuries.

A TSB track examination found signs of previous rail creep; during repairs after the derailment, rail anchors had been repositioned by up to 4 inches, and an adjacent siding showed anchors had been displaced by up to 6 inches. All displacement was eastward, the direction of the subdivision’s heavy-tonnage traffic. Displacement of 4 to 6 inches can take months or even years to develop, according to the report.

The TSB describes rail creep as a sign of compressive stress in the rail that can lead to rail buckling (lateral misalignment). Buckling can be caused by a combination of train dynamic forces (friction, braking, acceleration, and flanging on curves; elevated rail compressive forces; and weakened track conditions, as when rail anchors no longer provide the required resistance. All were present, the TSB found, and the location of the derailed cars near the end of the train indicate buckling likely occurred as the rear portion of the track traveled through the derailment site. Another derailment involving track buckling had occurred three weeks earlier at Mile 73.5 on the same subdivision.

In an October letter, the TSB advised Transport Canada that it might wish to review CN track inspection and maintenance practices on the Fort Frances Subdivision, particularly regarding rail de-stressing, securement, and movement. Transport Canada indicated in a December response that it would conduct a track inspect of the subdivision in 2026.

The TSB conducted a class 4, limited-scope investigation of the incident, which it describes as intended to advance transportation safety through greater awareness of potential safety issues.

— To report news or errors, contact trainsnewswire@firecrown.com.

“In an October letter, the TSB advised Transport Canada that it might wish to review CN track inspection and maintenance practices on the Fort Frances Subdivision, particularly regarding rail de-stressing, securement, and movement.”

Maybe? ‘Ya think?

“Transport Canada indicated in a December response that it would conduct a track inspect (sic) of the subdivision in 2026.”

So after two derailments in three weeks, both apparently attributed to maintenance deficiencies, CN walks away with no changes to their practices, no substantial fines or other regulatory pressures, and TC will take their time and mosey on down for a pre-announced future inspection months later? Talk about ineffective government regulation.

What will it take for CN to realize the value of having functioning rail anchors on mega-tonnage routes such as this one?

For once, we have a real explanation of a derailment. And it was a maintenance failure. Sound like they need heavier rail and perhaps concrete ties. Definitely more rail anchors.

What was not specified is how many ties were the rail anchors applied to. Was it every other tie that we see around here except at certain location it is every tie.

Rail creep is expected, especially on highly stressed tonnage lines, but it must be monitored and controlled.