EAST LANSING, Mich. — The Union Pacific-Norfolk Southern merger is unlikely to revive carload traffic — and it’s an open question whether it can unlock intermodal growth because of broader economic trends that are beyond railroads’ control, a Michigan State University supply chain management professor said during a webcast today.

UP says its proposed $85 billion acquisition of NS will improve service, create faster transit times, and lead to volume growth by eliminating interchange friction. The railroads also say that new single-line service will enable them to effectively tap the growth potential of the so-called watershed area in the country’s midsection. In all, they project $2 billion in net synergies.

But Jason Miller, the Eli Broad Endowed Professor of Supply Chain Management at MSU, questioned whether even a transcontinental railroad can reverse the declining fortunes of carload traffic.

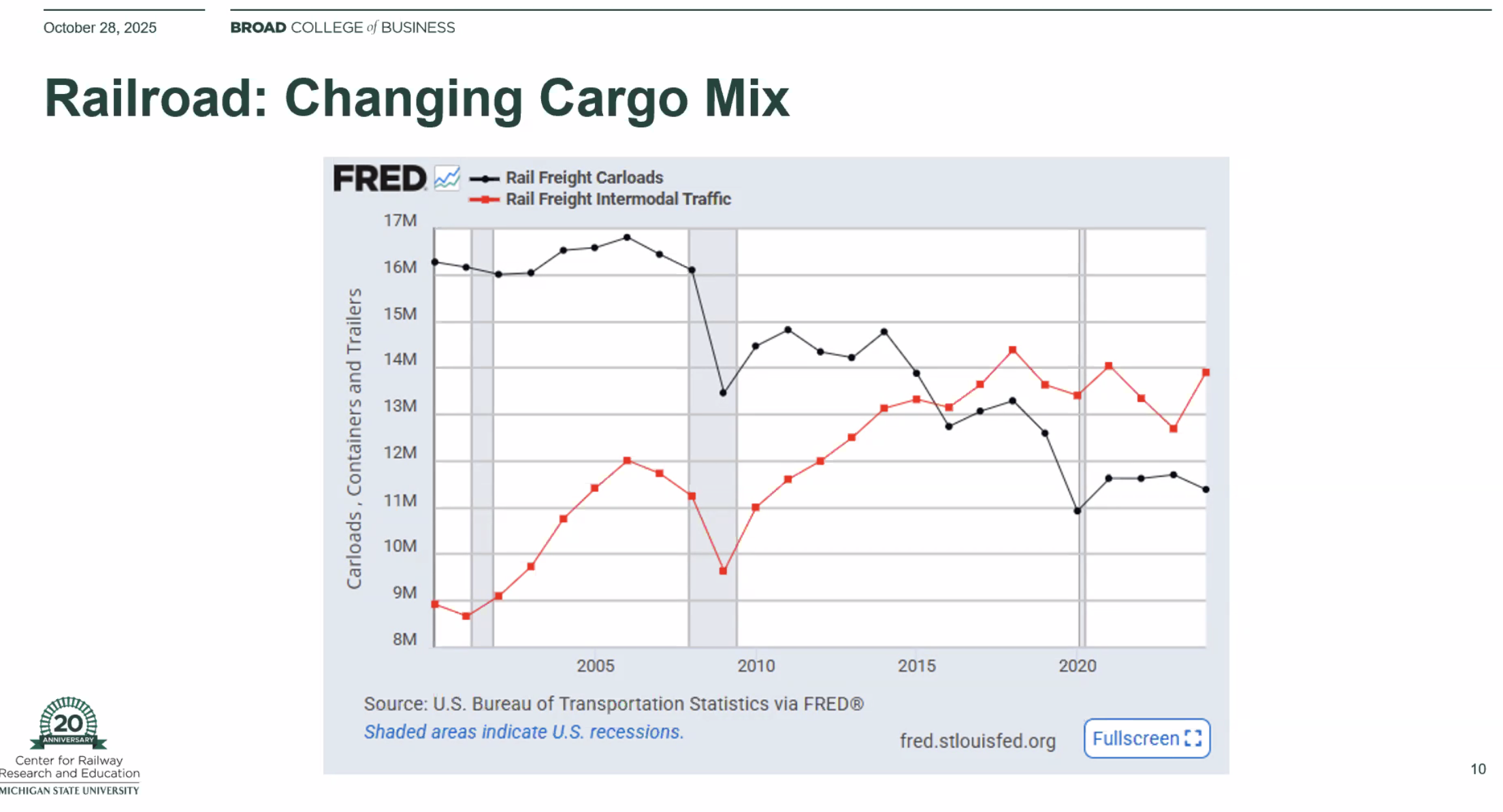

Rail traffic peaked in 2006, when railroads originated around 17 million carloads. Since then the long-term decline of coal — which remains the top carload commodity by volume — has dragged down overall volume.

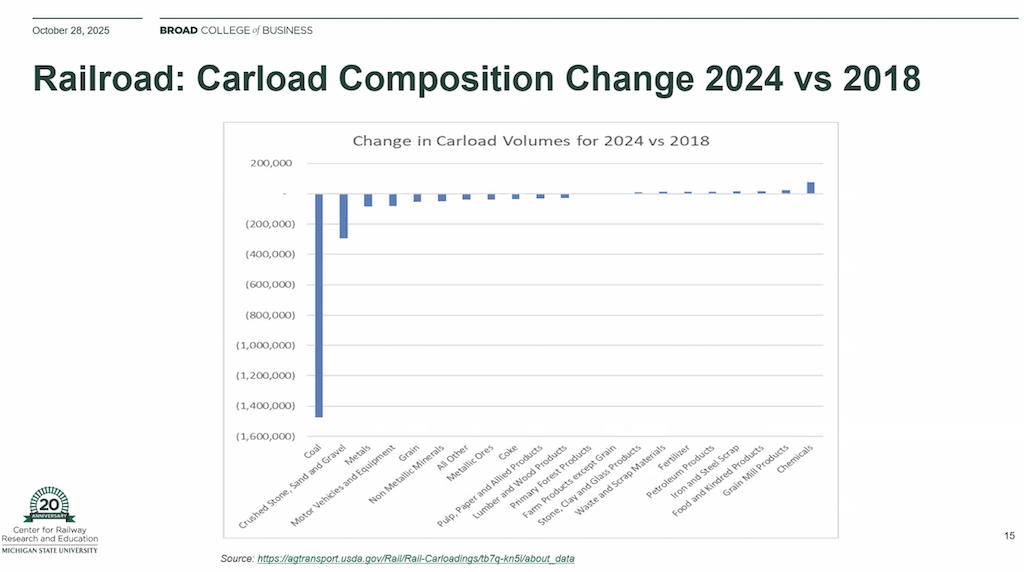

Comparing 2024 and 2018 carload volume shows that the decline is not just a coal phenomenon. Chemicals, the second-largest carload segment, has grown. It has not been enough, however, to offset the decline in 11 commodity segments, including major categories such as sand and gravel, metals, finished vehicles, grain, metallic ores, and petroleum products.

“We have passed peak carload. We will not get to 17 million car loads a year. That number is long gone. We can essentially forever forget about that,” Miller says.

Chopping a day or two off transit times through a transcontinental merger will not be enough of an incentive to lure shippers back to carload, he says.

“This is the brutal reality the Class Is face,” he says.

Intermodal has grown over the past 25 years. But Miller says that growth has been tied to two factors: The surge in containerized imports and years when trucking supply was tight.

Three recent intermodal peak years — 2018, 2021, and 2024 — show this dynamic at work, Miller says.

In 2017-18, truckload rates rose amid historically tight capacity. In 2018, imports grew in order to beat 2019 U.S. tariff deadlines. In late 2020 and 2021, volume surged as consumers, unable to spend on services during the pandemic, splurged on imported goods. And the 2024 spike in volume was again driven by retailers pulling forward imports to avoid tariffs.

Uncertainty over U.S. trade policy, the extent to which manufacturing returns to the U.S., and the potential for consumers to adjust their spending habits due to tariffs all might shape intermodal volumes in the coming years, Miller says.

The ebb and flow of trade and international intermodal volume will make it challenging for UP-NS to dramatically increase their intermodal traffic, Miller contends. Another trend running against the railroads is that more imported cargo bound for destinations in the Eastern U.S. is landing at East Coast ports, making the freight more likely to move in relatively short hauls via truck.

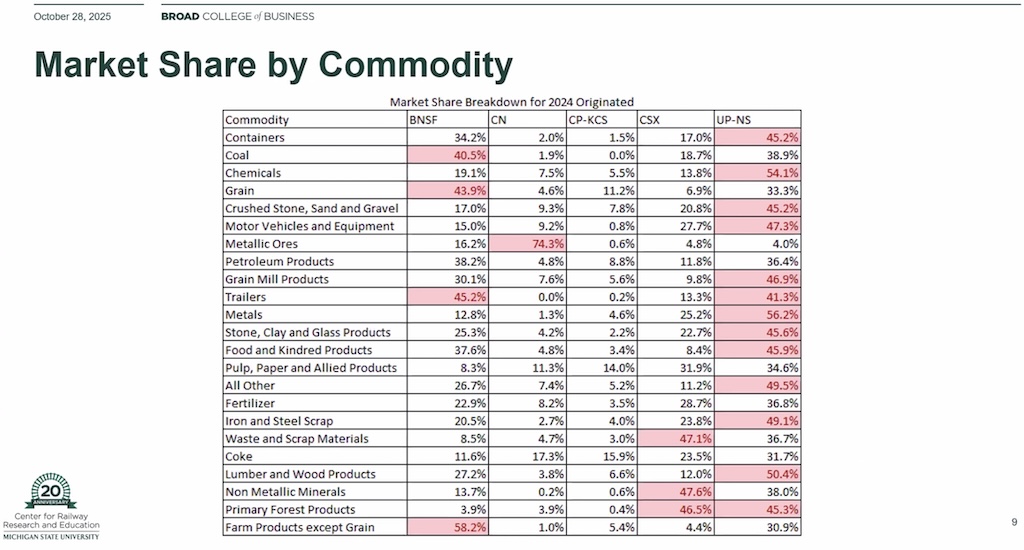

Although the direction of intermodal traffic is unclear, Miller says one thing’s for certain: UP and NS will be a “super Class I railroad.”

“This would truly be a unique entity … The scope of the connectivity across the United States with a UP-NS is just something that we have never seen before,” Miller says.

A transcontinental UP would have a dominant market share of 40% or greater in the majority of commodities that railroads haul, from containers and autos to chemicals and sand and gravel, Miller says.

Miller spoke on Tuesday afternoon during a webcast, “Railroads Reimagined: The Proposed UP-NS Merger & Its Supply Chain Implications.”

Chris: one more thing on loss of single car traffic. In addition to those mentioned railroads also got rid of team tracks in smaller towns (and later larger towns) which was the way lumber companies received sheet rock, cement, lumber and other items. When any track improvement (new rail etc) was done those sidings were ripped out whether or not those sidings were busy, or occasionally used. So it all went to trucks. In my own small town MP and UP did that.

There is concern over the economic power that would be possessed by just two “transcons.” Well, then is four the “right” number of transcons (some reassembly required)?

a. Burlington Northern + Norfolk and Western

b. Union Pacific + Chessie System

c. Santa Fe + Seaboard System

d. Southern Pacific + Southern Railway

I think you forgot the Mid-Atlantic and New England and the eastern Midwest. They weren’t served by any of the legacy railroads you named.

The biggest problem… Those ships have sailed. The second biggest problem: Car Load traffic is never coming back to rail, except as part of intermodal shipments offered by FedEx and UPS, or specialty moves. There is no mechanism for handling car load freight, except in full carload commodities such as Oil/Petroleum products, Canned Goods, Grains and milled products, Chemicals and Minerals, and Specialty items that require special handling. Any other item will be in a container handled by UPS/FedEx or on a plane by these and other freight forwarders. When I was a kid, I remember my dad buying fruit tree seedlings from a nursery back east and delivered to my home area, Logan, UT, by REA Express on the local UP freight in the required baggage/passenger combine car next to the caboose. When those cars were no longer used then that specialty “package freight” was carried in the caboose. But eventually, that freight went by truck via parcel post or a nationwide common carrier like Consolidated Freightways (nee Conway) Yellow, Roadway or the Like. Now many of those carriers are gone as well. Railroads have tried to revive small package freight and all have given up. Even Amtrak Express died. The fact is, only BULK car load freight still survives but it is not fast so UPS and FedEx will have continue that lane, because its a dead end on the railroads. Intermodal or full car loads (Cabbed Goods, lumber, corrugated packaging, steel, etc;) are what is and will continue ti happen. Going to the train depot to pick up a package from a far off city was a real adventure back in the day. But time has rolled on an that day is extinct. Sad, but true…

One of the big scandals with trucking no one seems to talk about is the cluster of states issuing CDL’s to, often illegal, immigrants who are in no way qualified and often seem untested despite that being required for a CDL. So there is a flood of people willing to do the grunt work of trucking and likely for very low wages.

Without this, would trucks be taking so many carloads?

There is a lot of that going on, and not just in trucking. Employers are seeking cheap labor. They don’t care if employees are legally qualified. Just make sure that their paperwork looks good. I’m not against immigrant labor, most of our ancestors came here seeking a new life, but let’s get them properly trained.

True Thomas, but most of our ancestors also came legally, not under the cover of darkness, trying to beat the system… I agree, no one is against legal immigration. Its the illiegal immigration and all those who prey on these immigrants that needs to be fixed. AND IT IS MORE THAN PAST TIME for Congress to do what it was elected to do and fixed the lasck of a legal way to bring the best and the brightest to this country…

The professor didn’t address asset stripping PSR and its effects. Price increases above inflation and 40% margins had their effect on stock prices and driving away customers. The Trains print article on killing RoadRailer service by NS said it all; a 10% margin on short hauls wasn’t enough the greedy executives and their hedge fund masters.

Since deregulation in the early 80s the decline in carload traffic was almost inevitable. Railroads were able to easily rip out spur tracks serving customers who were considered less profitable. And this repeated itself yearly until now most businesses even when situated along rail lines don’t ship by rail. Add to this the consolidation of class ones, poor customer service, abandonment of thousands of miles of track, the advent of PSR and the laser focus on operating ratio and it’s a wonder railroads have held on to the business they still have.

Rail Intermodal is a euphemism for more trucks, albeit on shorter hauls.