Water features in our garden railroads are popular for good reasons. They add the realism of real water, moving and highly reflective, and they are a delight to the eye and ear. At the same time, they present unique challenges in building and maintaining. One of these challenges is getting the water feature to blend in with the rest of the landscape, to appear like it belongs in the setting without that “pasted in” look. This has a lot to do with the edging material used and the artistry in effectively handling the interface between two different elements, land and water. I’ll share some ideas on the subject and give you a look at a unique approach to the challenge.

Choosing the right edging material

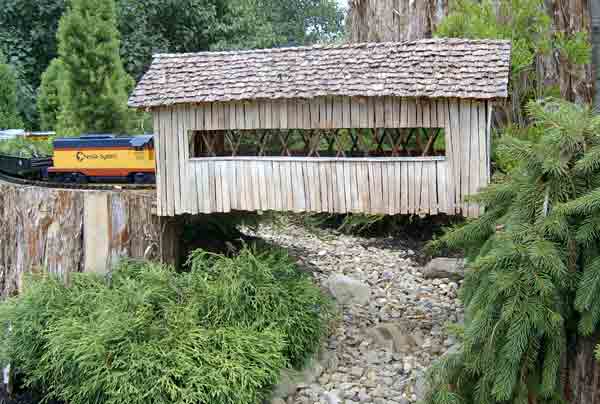

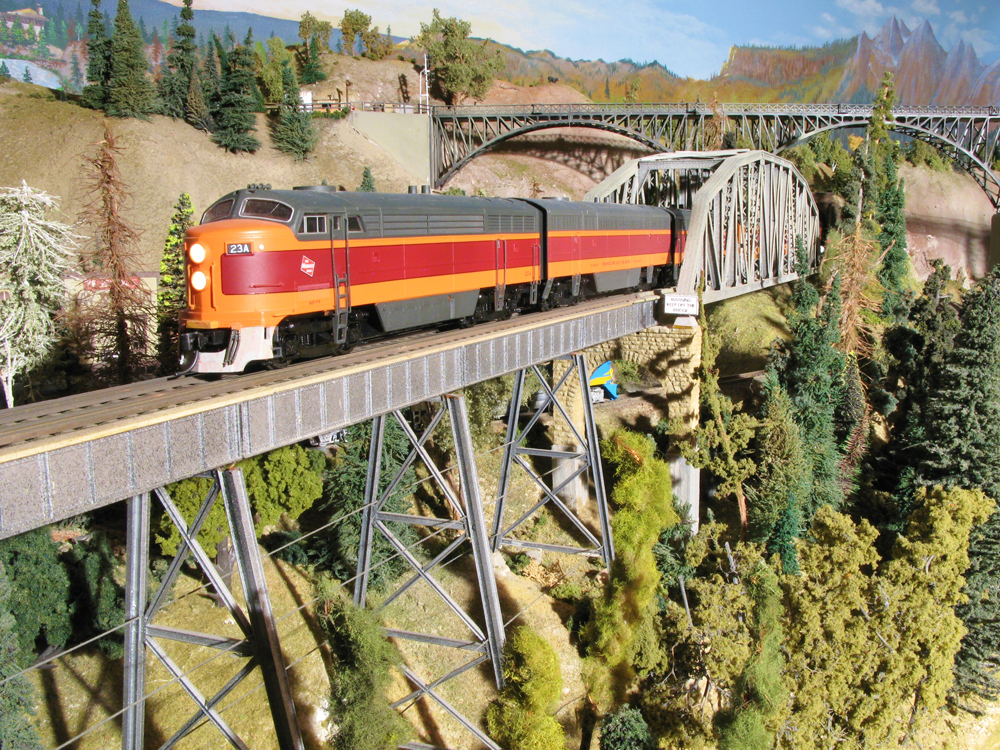

The choice of material to use in edging a water feature depends a lot on the surrounding landscape. A stream that runs through a rugged, stony terrain will be lined with rocks that match the surrounding landscape. This situation is typical of mountain streams that cascade down steep inclines (photo 1). Streams that meander through more level terrain will be lined with rounded, water-weathered stones. A mix of smaller and larger stones will add to the interest and realism of the stream bed (photo 2). A stream that flows through an environment that flourishes with plant life will be lined with water-edge vegetation.

Ponds, like lowland streams, are usually surrounded with vegetation, unless they represent high mountain lakes where vegetation is sparse. Most natural ponds have dense plant populations on their banks, whereas impounded ponds may have gravelly shores and rock-lined edges, along with some plant material. One example of an impounded, or dammed, pond is a mill pond, providing hydraulic power for a grist mill or a sawmill. The material lining the shores of these water features will depend on where they are located. The nature and look of the landscape around them should blend with the edging (photo 3).

Rocks or no rocks

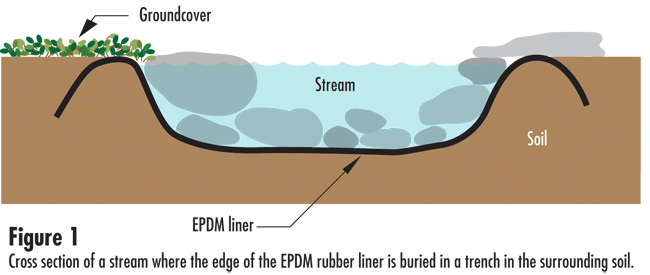

One of the limitations that makes it hard to disguise our water features’ edges is the lining material that is used. EPDM (ethylene-propylene-diene-monomer) rubber and polyvinyl plastic liners must be anchored at the edge to keep them from rolling or sliding back into the waterway. This makes the use of rocks more or less essential.

However, there is an alternate method of anchoring the liner without relying on rocks for anchoring weight. This involves burying the edge of the liner in a trough, using the weight of the dirt to hold it in place (figure 1). The surrounding soil will need to be lower than the shoulder of the liner to keep dirt from being washed into the water. Groundcover or other low vegetation can be planted in the soil near the buried liner and will eventually grow over and hide the liner edging. Although soil doesn’t actually touch the water’s edge, this technique comes close and makes the waterway look natural.

One of the streams I built on my previous garden railroad did have soil and rocks at the water’s edge. This was not a recirculating system (which must be maintained dirt-free for the pump’s sake), as I used water from the nearby lake, pumped to the headwaters of the stream. Vegetation grew thickly along and into the stream, giving it a wetlands-waterway look (photo 4).

A hanging garden

One of the more unusual ways of disguising a pond edge that I have seen is used by Mark Langan, of Mulberry Creek Herb Farm. He has a preformed plastic pond shell in his garden railway that is typically difficult to blend with the surrounding landscape (photo 5). His technique uses chicken-wire forms that he drapes over the edge of the pond (photo 6). Water-loving plants, with their root balls wrapped in course sphagnum moss, are worked into the wire webbing. The moss will wick up water from the pond to supply the plants. Golden spikemoss, a.k.a. clubmoss (Selaginella braunii or S. kraussiana ‘Aurea’, Zones 6-11) can be used as filler, providing a subtle background for the more showy plants (photo 7).

Some of the plants Mark Langan finds that work well in this method include dwarf horsetail, or scouring rush, (Equisetum scirpoides, Zones 5-11), Japanese mini sweet flag (Acorus gramineus ‘Oborozuki’, Zones 4-11), and small hostas, such as Lemon Frost, Baby Bunting, and Teeny-Weeny Bikini (all about 2″ tall and rated for Hardiness Zones 5-9). This is a labor-intensive process that will need to be, at least partially, repeated each year. However, the lush look and convincing pond-edge treatment make it worth a try.

Other edging

In nature, streams also run through dense, wooded areas. It’s not possible, with our usual lining materials, to grow scale trees on the banks of our streams and ponds. However, this can be suggested with dry stream beds. Miniature trees and shrubs can be planted on the very verge of a dry stream bed. The rounded stones along the edge of this represented stream can nestle right up against the roots and trunks of trees. The effect evokes a wilderness seasonal stream cutting through a stand of conifer trees (in the west) or willows and alders (in the east, photo 8).