Some of us are just plain tinkerers. We like to oil, adjust and run well-engineered pieces of machinery. Combine that with a love of railroading and you have the natural ingredients of someone who finds his way into operating small-scale live steam locomotives.

What are “small scales”?

The most popular scale is 1:32 scale, which operates on G gauge or 45mm track and are models of standard gauge prototypes. Aster Hobbies is the best-known manufacturer of these locomotives with models of American, British, German and Japanese prototypes. Denatured alcohol, butane gas or even coal fuels them.

Another scale is 1:20.3. Locomotives in this scale are models of two-foot or three-foot narrow gauge U.K. and U.S. prototypes. They operate on O gauge and G gauge track, and most can be changed from one gauge to the other by adjusting the wheels on the axles. Butane is the fuel of choice. Roundhouse Engineering Co. and Accucraft Trains are manufacturers in this scale.

What’s it like to fire up a small-scale steam locomotive?

First, take a look to see that the mechanical gear is in good condition. Are the nuts and bolts of the running gear loose? If not, now’s the time to tighten them up. After everything has been tightened up, lubricate the moving surfaces with a light grade of machine oil.

Next, you need to add steam oil to the lubricator. Just as with the prototype, the lubricator allows a small amount of steam oil, a special light grade of oil that is able to mix with steam from the boiler, to lubricate the internal portions of the cylinders and valves. After the lubricator has been topped off, add distilled (not tap) water to the boiler. Follow the manufacturer’s directions for the amount of water to add.

Finally, it’s time to add the fuel. Although some small-scale live steam locomotives run on denatured alcohol and still fewer on coal, the locomotive we’re firing up runs on butane. Add the butane into the gas tank through the fuel filler valve. It’s just like re-filling a butane cigarette lighter.

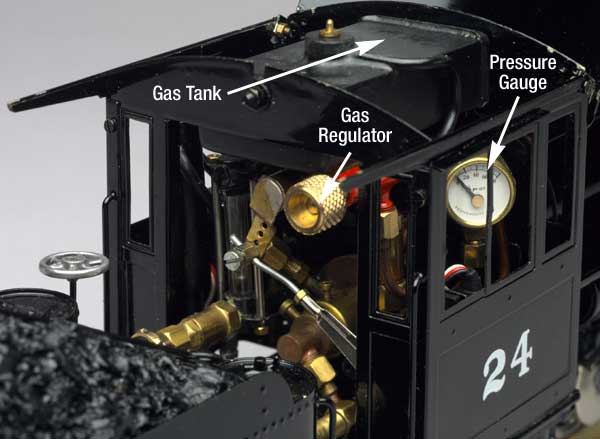

A look inside the cab of a live steam G scale locomotive. Now that everything has been checked, lubricated and filled up, we’re ready to light the burner. Hold a lighted match, cigarette lighter, or charcoal grill lighter over the top of the smokestack and slowly open the gas regulator. A small popping sound indicates that the gas has ignited, starting the process of converting water into steam.

Some locomotives have pressure gauges; some do not. It is fair to say that the locomotive is ready to run when the safety valve blows off excess steam. This usually happens when the water pressure in the boiler reaches 30 to 40 pounds per square inch. After that, the gas can be cut back to make enough, but not too much, steam.

Live steam accessories

Engage the locomotive’s valve gear in the forward position and open the throttle slightly. At first some water will discharge with steam from the smokestack. This happens because the cold cylinders condense the steam back into water. As the cylinders warm up, however, this initial priming process will cease. As the internal parts warm up, the locomotive will operate more smoothly.

Some locomotives are equipped with water refilling valves and some Gauge 1 locomotives have on-board pumps and bypass valves. These make long continuous runs quite possible. Without them, most locomotives will still operate 20-50 minutes without adding fuel or water.

When the run is at last done, the lubricator should be emptied and the engine wiped down. A final check of the mechanical bits and pieces and the locomotive is ready to be returned to the shelf or shed to await its next call to duty.

What’s the fascination with small-scale live steam?

Most model railroaders are interested in running a real but miniature railroad with all of the operating problems faced by real railroads. Some strive to build a realistic looking slice of the railroad world. Others find a grand challenge in building highly detailed rolling stock or locomotives.

But what stirs the imagination and efforts of the small-scale live steam crowd? For most of us, we are looking for the ultimate steam run. For some that means the length of a run. Can the engineer conserve fuel and water and coax an extra few minutes out of the engine? For others it is seeing their locomotive strain to pull a long train of freight or passenger cars. Many simply savor the sight of a fine plume of exhaust steam and the smell of steam and hot oil mixed together. They enjoy watching little wheels whirling around as the result of miniature mechanical parts coming into concert in response to the press of steam.

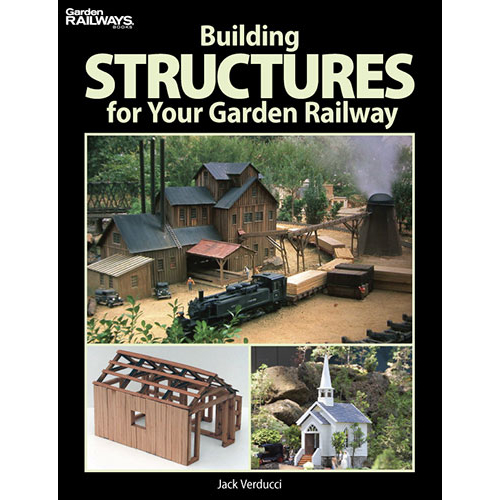

But that’s not all. Many small-scale live steamers build highly detailed trains to run behind their locomotives. They build line-side structures to give a greater feeling of railroad realism to their locomotive operations. Because most live steam railways are built outdoors, the whole family can get involved by growing a garden to complement the railway. Live steam can coexist with track-powered railways and brings an extra dimension to garden railroading. Small-scale live steamers also use battery-powered locomotives when there’s not enough time to raise steam.

How much does it cost?

This English-profile locomotive is a beginner’s live steam model and retails for $580

Beginner locomotives cost in the $400-600 range. The largest locomotives require an investment of several thousands of dollars. Most live-steam enthusiasts own one or two or a few locomotives and a few cars and buildings. The overall cost may be less than the average N or HO scale modeler spends on a small layout and equipment. Fuel, oil, and water cost less than a dollar per run.

Where can I learn more?

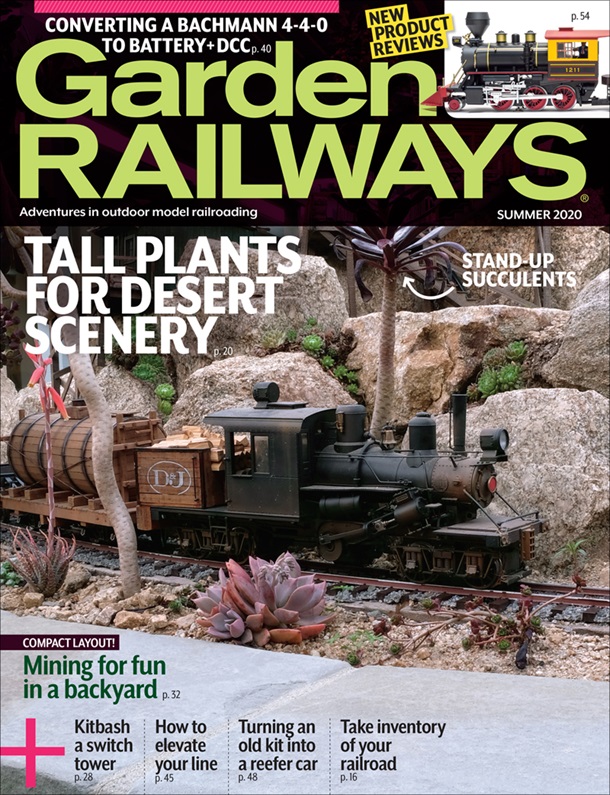

Garden Railways magazine often has articles about small-scale live steam. Steam in the Garden is another magazine devoted to small-scale live steam.

There are also regional and national steam-ups where people gather to run their locomotives. The best known steam-up in the U.S. occurs each January in Diamondhead, Miss., (one hour east of New Orleans). Nine years ago 52 live-steamers gathered for the first Diamondhead meet and ran locomotives for three days. Last month over 200 people from the U.S. and around the world gathered to run locomotives for over a week.

Come take a look. If you are a tinkerer by nature, you may just find a modeling home in small-scale live steam.