My first railroad book has stuck with me ever since my parents gave it to me when I was 9. Lucius Beebe’s “Hear the Train Blow” was a massive scrapbook of American railroad history, full of the author’s outrageous prose and uncanny skill at digging up illustration. I still love looking through it 62 years later.

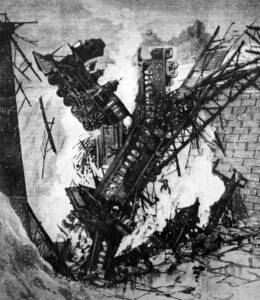

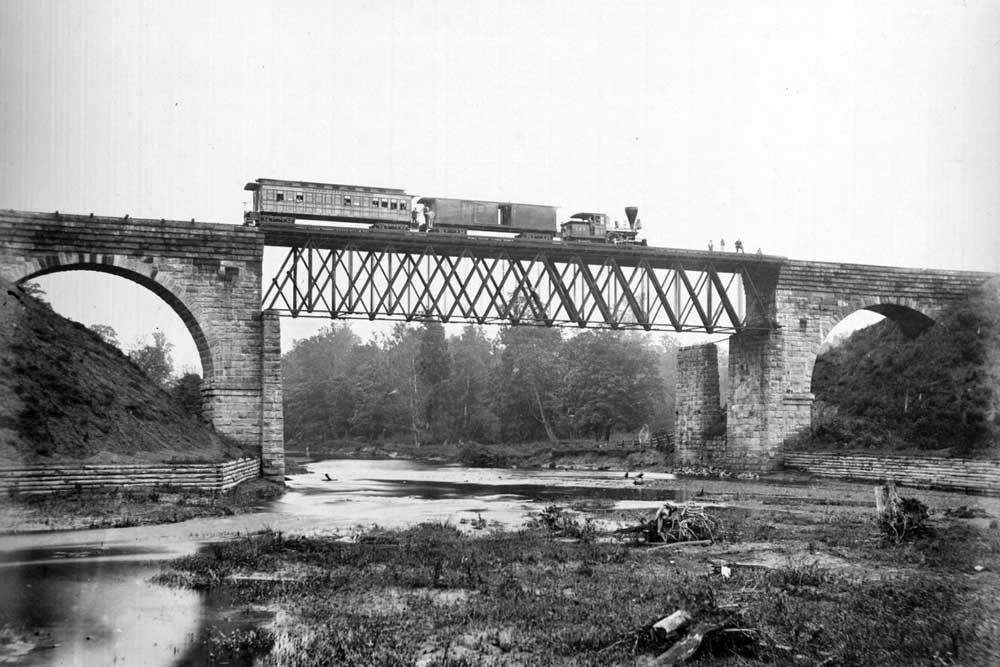

Nothing in it has stayed with me more than his chapter “The Open Switch,” a look at railroad safety in the 19th and early 20th century. The section leads off with a horrifyingly surreal 1865 drawing, showing the Grim Reaper astride a creepy-looking 4-4-0 rolling over screaming victims. Awful but compelling stuff for a kid.Another illustration grabbed my attention just a few pages into the chapter: a vivid image of the moment on Dec. 29, 1876, when the Lake Shore & Michigan Southern’s westbound Pacific Express plunged into Ashtabula Creek at Ashtabula, Ohio, as the Howe truss bridge it was crossing collapsed like a Tinkertoy. Statistics vary depending on the source, but the tragedy killed at least 81 passengers and crew and injured another 90 or more, many of them in the fire that ensued. For its era, it was all too familiar.

Wrote Beebe: “The causes of the worst wrecks of the nineteenth century were defective bridges and the car stove. The possibilities for holocaust inherent in a red-hot cannonball stove in each wooden passenger car coach that might go into the ditch were enormous. Wrecks with the greatest casualty list were almost inevitably accompanied by fire.”

In fact, the trade magazine Railroad Gazette later reported that in the five years after 1873, American railroads experienced at least 126 bridge failures. Ashtabula wasn’t unusual; it was just the worst.

Like most accidents of this scale, Ashtabula created a number of story lines: changes in bridge design, away from the Howe truss and its use of wrought iron; public outcry for regulation of the railroads; even the deaths of several of the principal figures. Shortly after the accident, LS&MS Chief Engineer Charles Collins shot himself to death, or perhaps was murdered; no one is certain. Bridge designer and contractor Amasa Stone — a major figure in Ohio business and politics — killed himself just 7 years later. It has even been speculated that New York Central titan Cornelius Vanderbilt’s death immediately after the accident at age 82 was hastened by Ashtabula.

If all of this sounds like the ingredients for a documentary, you’re right. Partners WQLN-TV of Erie, Pa., a PBS station, and Canal Fulton, Ohio-based Beacon Productions have done just that, creating “Engineering Tragedy: The Ashtabula Train Disaster,” a two-hour documentary that saw its screen debut this past weekend in Ashtabula and will have its official premier broadcast Dec. 29, the anniversary of the wreck. The producers have created an information-packed website for the film.

Although I haven’t seen the film yet, its trailer offers intriguing glimpses of dramatized courtroom scenes, actors done up in 1870s finery, the Ashtabula site today, even scenes aboard the train. For the latter, the producers called on one of Ohio’s standout railroad museums, the Age of Steam Roundhouse in Sugarcreek, some 130 miles southwest of Ashtabula. One of its locomotives, McCloud River 2-6-2 No. 9, served as a stand-in for LS&MS Socrates, including scenes inside the cab. The second locomotive on the ill-fated train, 4-4-0 Columbia, fell into the river.

No. 9 is a real boomer, having worked for a number of railroads across the continent. Baldwin built the Prairie type in 1898 for McCloud River, where it worked until 1934, followed by stints on the Yreka Western, Amador Central, Nez Perce & Idaho, and, beginning in 1964, stops in Wisconsin on the Mid-Continent Railway Museum and Kettle Moraine Railroad. Age of Steam’s founder, the late Jerry Joe Jacobson, bought the engine in 2015.

Although No. 9 doesn’t currently operate, the use of steam, green screen, and fake snow made the locomotive look credible when the “Engineering Tragedy” filmmakers showed up to shoot scenes in November. Although 12 to 15 hours of shooting around the roundhouse netted only a few minutes on screen, AOS staff considers it an honor to be part of the project.

“Ten years of production and thousands of man hours have been invested in this two-hour final product,” explains Pete Poremba, Age of Steam president. “Everyone involved in producing it was driven by how important this event was to the people who lived through it, lost loved ones because of it, or learned lessons to enact change to avoid another similar catastrophe.”

As Poremba explains, telling stories about history is in Age of Steam’s DNA. “Whenever he could, Jerry cooperated in providing the necessary historic equipment and backdrop for productions. The museum is proud to carry on that tradition today.”

One of the film’s producers, Len Brown, says the show might be the largest all-volunteer film project ever undertaken by a PBS station. More than 350 actors and crew members participated.

“The production work on re-creating the crash is amazing,” says Brown. “Not only did we go to period locations, but we also used a huge green-screen location to really bring it to life, make it as realistic as we could. And we did it on a shoestring budget. All of our money went to location fees, transportation, hotels, costumes — nobody got paid, including me. We just wanted to bring this amazing lost story of American history to life.”

Producer Brown says he has commitments from PBS stations across Ohio and Pennsylvania to broadcast the documentary and WQLN itself has scheduled the premiere for 8 p.m. Eastern on Thursday night, December 29, the 146th anniversary of the tragedy. If you have an interest in seeing the film, Brown urges you to contact your local PBS station; distribution is free to stations who want it. You could also contact WQLN for more information.

Meanwhile, I can’t help but revisit one of Beebe’s wise conclusions about Ashtabula and other legendary railroad disasters: “Inevitably, along with their useful and valuable cargoes, the speeding cars were also freighted with disaster. Wrecks and other byproducts of mischance began to appear early in the record, and it is improbable that they will ever entirely be eliminated until the last carwheel stops rolling on the last rail.”